Column: The real victims of the port logjam are its neighbors and workers. Don’t make it worse for them

California’s business community didn’t really have to put its proposed solutions to the epic logjam at the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach in writing, as it did in a recent letter to Gov. Gavin Newsom.

Anyone familiar with how business leaders react to any purported crisis affecting them could have predicted that they would try to take advantage of the temporary backup at the port to push their long-term wish list: Cut regulations. Require workers to labor longer hours for lower pay and with fewer workplace protections. Drop environmental quality concerns into the dumpster.

Never mind that most of these options would do little to relieve the backup at the ports. They would, however, undermine newly passed state labor laws and fulfill their enduring goal of eviscerating the groundbreaking California Environmental Quality Act.

All that 24/7 operation is going to do is create more negative health impacts on the community. Already we can’t have clean air in our own homes, because of the port.

— Long Beach community activist Theral Golden

CEQA, as it’s known, has been a target of builders and industrialists ever since it was signed in 1970 by Gov. Ronald Reagan.

The business community isn’t waging this war alone. It has the backing of anti-regulation libertarians such as Virginia Postrel, who in a recent opinion column for Bloomberg attributed the port logjam to California “Nimbyism” (that is, the not-in-my-backyard syndrome).

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

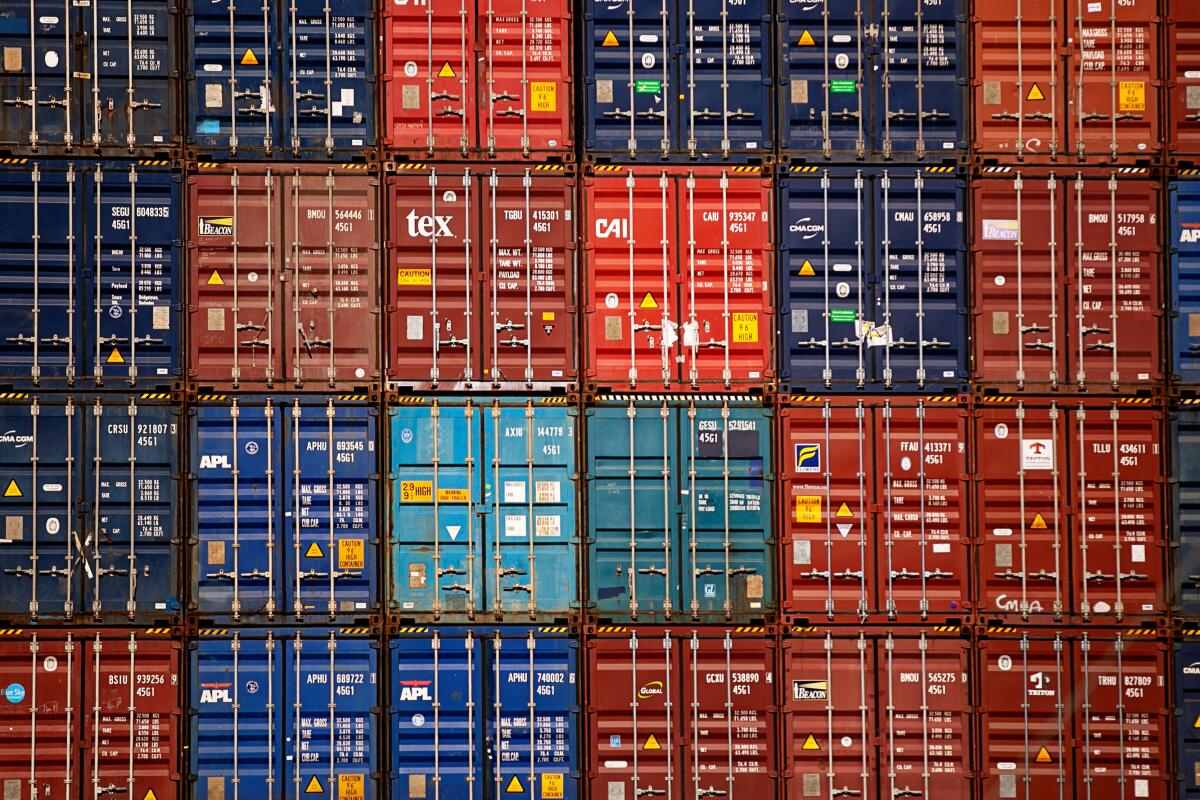

Postrel concluded that “the main problem” causing the logjam was a lack of storage space for empty shipping containers at the port, which prevented full containers from being offloaded from ships. And that the main reason for the space constraint was a Long Beach ordinance preventing more than two containers from being stacked atop each other onshore.

This is “not a safety regulation but an aesthetic one,” she wrote: “City officials decided that stacks of containers more than eight feet high were too ugly to tolerate.”

Postrel drew her conclusion from a Twitter thread by Ryan Petersen, a portside business entrepreneur who provided his diagnosis after touring the port Oct. 21, as my colleague Sam Dean reports.

Beyond rather overstating Petersen’s own point, hers was manifestly ludicrous. The logjam is the product of a confluence of many factors, including but not limited to storage space on land.

Juan Lara was headed back to the Port of Los Angeles two weeks ago from his daily pickup in the Mojave Desert when his truck erupted with engine trouble.

Indeed, there are indications that the major factor in the logjam is what economist Dean Baker identifies as “extraordinary demand” for goods, which is likely to fade in upcoming quarters. Even the letter-writing business leaders acknowledged that as a factor, if begrudgingly: “We agree that some of the port congestion is driven by pent-up demand,” they wrote.

Like the business leaders, however, Postrel drew a line from the port problems to, yes, CEQA, asserting that the law helps explain why “the formerly can-do state of California has become such a difficult place to build anything.”

Her implicit argument is that CEQA has put too much power in the hands of local residents, who are thus able to interfere with developments with more important, albeit nonlocal, benefits.

She called this “a classic example of a well-recognized issue in political economy.... The benefits of the policy [in this case, the battle against visual pollution in Long Beach] are concentrated while the costs are dispersed.”

I’d put it another way. The benefits of lax environmental and workforce policies at the ports and related businesses are dispersed (among consumers nationwide), but the costs are concentrated (upon neighbors and workers).

This is the core of the fight for environmental justice, in which low-income neighborhoods in Long Beach and warehouse floors in the Inland Empire are key battlegrounds.

So let’s take a look at how the transport industry in general and the port specifically affect those who live and work in their proximity.

Proposition 22 is a revolutionary step in the influence of tech-based businesses in our daily lives in general and the lives of workers in particular.

We’ll start with the port’s neighbors.

Air quality in the Los Angeles and Long Beach communities ringing the port has long ranked among the worst in the country. Asthma and cancer rates are among the highest; the 710 Freeway corridor, the principal thoroughfare feeding the port, has been dubbed “asthma alley.”

Concerns about local residents’ health dates back decades; in 2008, the California Air Resources Board estimated that there were 3,700 premature deaths a year directly attributed to the port and pegged the annual cost, including medical care and missed school and work days, at about $30 billion annually.

“The health impacts have been overlooked and are really significant,” says Andrea Hricko, professor emerita in environmental health at USC. For many residents, there’s no escaping the pollution.

On Oct. 17, Union Pacific Railroad expanded the hours of operation at its rail transfer facility at the Port of Los Angeles to 24 hours, seven days a week, adding 20 hours weekly to accommodate stepped-up port operations. The change won the railroad a note of thanks on LinkedIn from port officials, but no acknowledgment of how it would affect local residents.

“People are living hundreds of feet from there,” Hricko told me. “Kids there are going to be suffering asthma all the time.”

The health effects of this level of pollution go deeper. A study led by the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health and published in April found that communities exposed to worse air pollution also had elevated COVID-19 mortality rates. Make no mistake: The residents of the most severely affected communities are disproportionately low-income and people of color.

Those effects are sure to be exacerbated by the measures being taken to clear the port logjam, such as round-the-clock operations, as President Biden has advocated. “We should not have to bear the burden of that port’s poor planning,” says Theral Golden, a longtime community activist in west Long Beach. “All that 24/7 operation is going to do is create more negative health impacts on the community. Already we can’t have clean air in our own homes because of the port.”

Workers at the port and associated businesses such as warehouse complexes in the Inland Empire are also bearing the burden of the logjam. Port truckers have been abused by trucking companies for years. They’ve been consistently misclassified as independent contractors despite having all the qualities of employees, and consequently denied the workplace protections afforded employees.

A California judge got it right: Prop. 22, California’s gig economy law, outrageously trampled on employee rights.

AB 5, the California law designed to put an end to misclassification in many industries, has been under fire by the trucking industry since its enactment in 2019. The California Trucking Assn., the companies’ lobbying arm, has sued to block its application to truckers, though a federal appeals court has said it can continue to be enforced in that industry.

The California Trucking Assn. is among the signers of the business leaders’ letter, which asks Newsom to “suspend AB 5 ... until the supply chain has been normalized” (among other proposals).

This month, the big port trucking company XPO Logistics agreed to pay $30 million to settle class-action lawsuits filed by nearly 800 drivers who said they earned less than minimum wage working from the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach.

As my colleague Margot Roosevelt reported, the settlements addressed allegations that the company paid drivers less-than-legal wages, failed to pay them for missed meal and rest periods, and failed to reimburse them for business expenses or for waiting-time penalties, including payments they’d be entitled to as a matter of course if they were classified as employees. The settlement follows awards of more than $50 million by California’s labor commissioner’s office to about 500 truckers who say they were misclassified as contractors rather than employees.

On the warehouse front, Newsom in September signed a pioneering state law, AB 701, that gives workers at warehouses operated by Amazon and other companies the ability to fight quotas, which critics say produce dangerous conditions by pressuring workers to skip bathroom breaks and cut corners on safety. The law prohibits penalties for stopping work to use the bathroom or other activities related to health and safety, and bars retaliation against workers who complain.

The business letter asked Newsom to “suspend implementation of AB 701 until the supply chain has normalized and goods movement has been restored.”

It should be obvious that environmental and workplace regulations like these are never as important as they are during a purported crisis, when managements are inclined to increase productivity as much as they can, health and welfare considerations be damned. When times are slack, after all, there’s little cost to letting workers go to the bathroom.

Advocates of suspending or even overturning regulations that benefit workers and communities are seldom those who are directly affected by the consequences. It’s all too easy to be condescendingly dismissive about ordinances that are aimed merely at “aesthetics,” as if any libertarian pundits would tolerate 20- or 40-foot stacks of containers deposited in their neighborhoods, or 24/7 operations of heavy equipment up their streets.

The business leaders who signed the Oct. 19 letter to Newsom were careful to place their concerns in the context of consumer welfare — nothing so crass as “to ensure there are toys in the shelves for Christmas,” they wrote. Rather, “we are asking for your leadership in order to ensure working families have access to affordable medical supplies, diapers, and other basic necessities.”

They wrung their hands over the environmental consequences of allowing large cargo ships to idle for days offshore, waiting for a berth at the port; never mind the environmental consequences of bringing that pollution onshore, where its effects have been endemic for decades.

Their concerns are a dodge. Their real goal is to hamper the progress that has been made, halting as it is, in improving the health and welfare of the people who help get goods from port to market or who are collateral damage in the process. This is the worst time to shoulder their interests aside, yet again.

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.