Column: Will the recall loss jolt the California GOP out of its death spiral?

Has anybody seen the California Republican Party lately?

One would have expected the state GOP to put its best foot forward during the recall campaign just ended. To set its best foot forward in an election that, thanks to its procedural peculiarities, presented its best opportunity in more than a decade to break the Democratic stranglehold on state government, if only temporarily.

As is obvious from the overnight election returns, that didn’t happen.

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

The Republicans couldn’t even coalesce around a single credible candidate as an alternative to Democratic Gov. Gavin Newsom, much less a policy package that cogently addressed the myriad social and economic problems facing the state of California: climate change, homelessness, economic inequality and, of course, COVID-19.

The state GOP hoped to use the recall to expose Newsom’s flaws as a governor. Instead, it reinforced its own image as a diminished party with almost nothing to offer California voters — not even a commitment to sound governance.

In a perfect world, the party out of power would serve the public interest as an effective counterweight to the policies of the party in power. A truth rarely acknowledged is that a sensible opposition is healthy for majority parties too.

It keeps them alert to the reality that there are reasonable limits to the exercise of political authority because the minority may not be that far from regaining power.

It may even produce ideas that can be incorporated in legislation, lending bipartisan coloration to policy if not in fact, at least in effect. A smart party leadership will do well to keep its eyes on what the opposition is thinking and where it’s finding strength.

Some cautioned that the recall and initiatives would become playthings of the powerful. That’s what’s happened.

In California, that hasn’t been necessary because the Republican Party has been largely out of business for years. The party’s decline can be traced to its advocacy in 1994 for the notorious Proposition 187.

The measure explicitly barred immigrants without documentation from state social and economic programs, but in reality it was an attack on all immigrants, especially Latinos. In effect it opened the door to racial profiling by law enforcement officers and others acting under color of law.

Proposition 187 passed with 59% of the vote but was subsequently invalidated in the federal courts. The record since then suggests that California’s ethnically diverse voting community didn’t forget or forgive: The GOP hasn’t won a statewide office since Arnold Schwarzenegger’s reelection in 2006.

There are hardly any signs that California Republicans have gotten the message that the key to returning to power is to develop positions and policies that address the genuine issues voters have with their state — policies that subject Democratic governance to serious criticism.

The Larry Elder campaign’s reaction to its impending defeat in the recall was to preemptively claim fraud, with a website belonging to the campaign even alluding to the “ammo box” as a means to “ameliorate the twisted results” of the election. (The reference to the ammo box apparently was removed from the website by Tuesday.)

Former President Trump weighed in with a statement calling the election “rigged,” an assertion for which there are absolutely no grounds whatsoever. Unless the GOP is prepared to say that its long drought in statewide office-seeking is the result of 15 years of rigged elections, it must acknowledge that voting fraud isn’t its problem. Blindness to voters’ interests is its problem.

That self-evident truth was on vivid display throughout the recall. We can examine the party’s deep illness by examining the platforms of the leading Republican candidates: radio host Elder, businessman John Cox, former San Diego Mayor Kevin Faulconer and state Assemblyman Kevin Kiley.

The general approach of all of them was to list the problems faced by the state and suggest that only they had the answers.

As my colleague Steve Lopez eloquently observed a few days before the election, many of the fixes they were selling — “tax cuts, restoring the death penalty, releasing fewer prisoners, school choice, harsher policies on immigrants, loosening coronavirus protocols, relaxing environmental protections, police enforcement of homeless encampments — are red-meat talking points rather than viable solutions to the state’s most vexing problems.”

Republican gubernatorial recall candidate John Cox thinks California should model its COVID policies after Florida’s.

That was certainly true of their approach to the pandemic, which began and ended with plans to undo Newsom’s initiatives in favor of the approach of such a paragon of scientific-based policies as Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis. Over the last seven days, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Florida ranks sixth worst in the nation in COVID cases per 100,000 population; California ranks 47th.

Let’s take a closer look at what the California GOP has put on the menu.

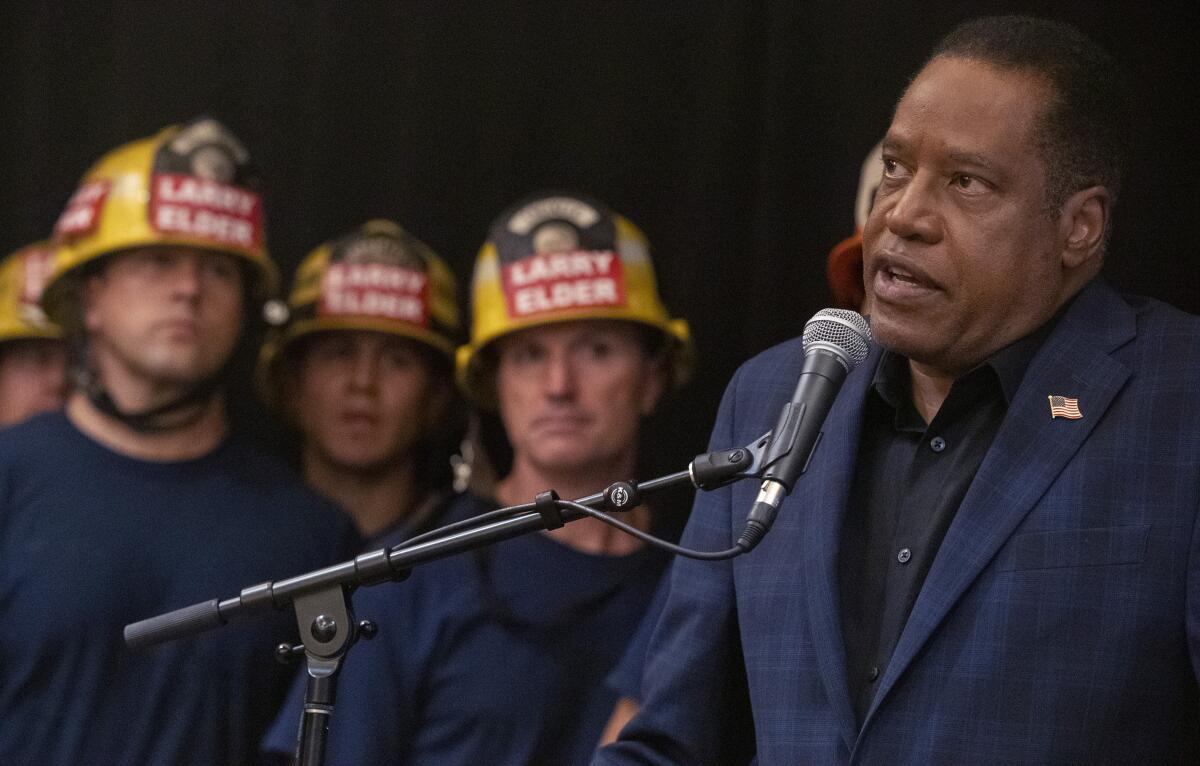

Of Elder there isn’t much to say, except that as the election drew nearer he increasingly gave the impression that he didn’t really care to run the state at all. He seem to be in the race merely to grasp the main chance, perhaps by raising his profile as a right-wing radio voice.

Otherwise, how would one explain the loopiness of his arguments — that the minimum wage should be zero, for instance, or that slave owners should be paid reparations for the loss of their slaves after the Civil War. (Never mind that the latter would be not only morally repugnant but also unconstitutional because the 14th Amendment specifically bars “any claim for the loss or emancipation of any slave.”)

A candidate seriously running for office in California or, really, any other state would take care when feeling the impulse to voice opinions like this to put a sock in it.

John Cox, who got trounced by Newsom in the 2018 gubernatorial election and apparently figured that he’d have a better chance in an off-schedule, low-turnout contest on the assumption that Democrats would stay home, offered to slash income taxes by $30 billion.

That would be about 40% of the expected personal income tax revenue for 2020-21, blowing a sizable hole in the state budget. Cox proposed to make up the difference in part by rooting out “waste, fraud and abuse.”

As we’ve pointed out before, the quest for waste, fraud and abuse is the go-to theme for any politician bereft of ideas — WFA, “the WMD of domestic politics. It’s handy for rallying the campaign troops, but the results on the battlefield always disappoint.” That’s because it means cutting programs, and the WFA-seekers know never to list the programs on their hit list because every one has a large cadre of supporters.

Cox, to his credit, focused some of his fire on the homelessness crisis. To his discredit, his proposed solution was a superficially simple plan that amounts to a conservative hobby horse: “treatment first,” instead of “housing first,” an approach that has been favored by homelessness experts for more than 20 years.

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis thinks boasting about his anti-lockdown stance and attacking Anthony Fauci are a winning political play for him, even as COVID rages out of control in his state.

Cox’s claim is that the housing-first approach of striving to get homeless people into shelters without demanding that they first get off drugs or alcohol or receive psychiatric care or employment training hasn’t worked.

It’s better, supposedly, to make treatment a condition of giving shelter. How these complicated treatments, which themselves often have indifferent success rates, are supposed to be delivered to a population without stable housing isn’t clear; some sort of housing has to be provided during treatment, but where?

Cox places great store in a series of articles by the right-wing Heritage Foundation, which in turn relies on a 2009 study out of the University of Alabama that it claimed to have documented “strong positive outcomes for the homeless” from a treatment-first system.

Except that the Alabama study came to no such conclusion. What it found was that housing first and the alternatives both have strengths and limitations, depending on what homeless population one is addressing. More to the point, “the evidence is sufficiently mixed and incomplete that assertions that scientific evidence shows how to ‘solve’ homelessness should be greatly tempered,” the researchers cautioned.

That, of course, is advice that Cox ignored. Instead, he claimed that his secret sauce would “cut homelessness in half” within 10 years. Oh, sure.

Cox might have shared his findings with Faulconer, who put forth as his principal achievement as San Diego mayor that he defeated the homelessness problem in his city, “the only big city in California where outdoor homelessness went down by 12% instead of up.”

What could a Gov. Larry Elder actually accomplish? Very little.

Except that Faulconer’s record doesn’t appear to have been so cut and dried. Homelessness advocates in San Diego say he was basically uninterested in the problem until an outbreak of the contagious hepatitis A virus among homeless San Diegans in 2017, the fourth year of his mayoralty.

After that and through the first year of the pandemic, he acted energetically, providing temporary and then permanent shelter in the San Diego Convention Center.

Faulconer’s claim to have cut homelessness by 12% warrants scrutiny. To some extent it’s the product of a change in how homeless people are counted and how they’re categorized. At best, moreover, Faulconer’s solutions were reactive and short term. Homelessness is surging again in downtown San Diego, only this time the problem belongs to Faulconer’s successor, Democrat Todd Gloria.

Then there’s Kiley, whose rapid-fire patter delivery tends to obscure the vacuousness of his ideas. Kiley’s platform appeared focused on burdening Newsom with a raft of unappealing adjectives — “lawless,” “corrupt,” “unscientific,” “incompetent,” etc., etc. Over-the-top rhetoric that sounds as if someone locked Kiley in a room with a thesaurus, but doesn’t really conform to what even Newsom’s critics think of his performance.

What does Kiley stand for, however, aside from being the un-Newsom? He’s in favor of “liberty,” of making California “free again,” of fighting critical race theory, of vaccination mandates. He claims to be a champion of the working person, even touting his recognition as “Legislator of the Year” by the Assn. of Independent Workers. This is an organization that promotes gig work, which is no path to economic self-sufficiency.

The award presumably reflects Kiley’s support for Proposition 22, the ballot measure on which its sponsors, Uber, Lyft and other gig companies, spent a record $200 million so they could continue their unrelenting exploitation of drivers and delivery staff by rewriting state labor law in their own image.

Longtime Republican political strategist Dan Schnur, who gave up his shingle to teach political communications at UC Berkeley and USC, told me a few weeks ago that the recall would yield less a judgment on Newsom’s record after three years as governor than a window on the future of the GOP, both in California and nationally.

“Elder is running as a candidate in Trump’s image,” he said, “Faulconer as a pre-Trump, traditional Bush or Romney conservative, Kiley as the next generation’s idea guy, and Cox as the outsider businessman. Even if the recall is defeated very soundly, those votes are going to tell us where Republicans are looking to go next.”

Yet what was on the ballot Tuesday was not the GOP’s future nationally, but in California. If this was the best it could do, it still has a long road to travel on its way back to relevancy.

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.