Teamsters’ push to organize Amazon: Will it work?

Delegates to the International Brotherhood of Teamsters convention voted overwhelmingly for a nationwide push to organize hundreds of thousands of Amazon’s warehouse and delivery workers, a formidable task given the e-commerce behemoth’s fierce antiunion stance.

“We will organize Amazon,” said the union’s outgoing general president, James P. Hoffa. “In my more than two decades of service, I’ve yet to see a threat quite like the one Amazon presents to hardworking people, small businesses, the logistics industry and our nation’s middle class.”

Thursday’s vote, which took place virtually, was 1,562 to 9, in favor of a resolution to help mobilize workers at the Seattle e-commerce giant.

With 1.4 million members, the Teamsters will “fully fund and supply all resources necessary” to address “Amazon’s exploitation of its employees, contractors and employees of contractors,” the resolution stated.

The union last year appointed Randy Korgan, secretary-treasurer of Teamsters Local 1932 in San Bernardino, to a position as national director for Amazon, and said it would create an Amazon division dedicated to the campaign.

The new effort is aimed not just at growing the ranks of organized labor but also at protecting wages, benefits and workplace standards in Teamster-represented companies such as UPS, which are under pressure to replicate Amazon’s relentless push for speed and productivity.

With the explosive growth of e-commerce, Amazon now employs 1 million workers and is on pace to become the nation’s largest private employer. The Seattle-based company did not respond to a request for comment Thursday.

Teamster locals have yet to file petitions under National Labor Relations Board rules to represent Amazon employees, according to a spokeswoman, despite the union’s dominance in labor-represented logistics industries.

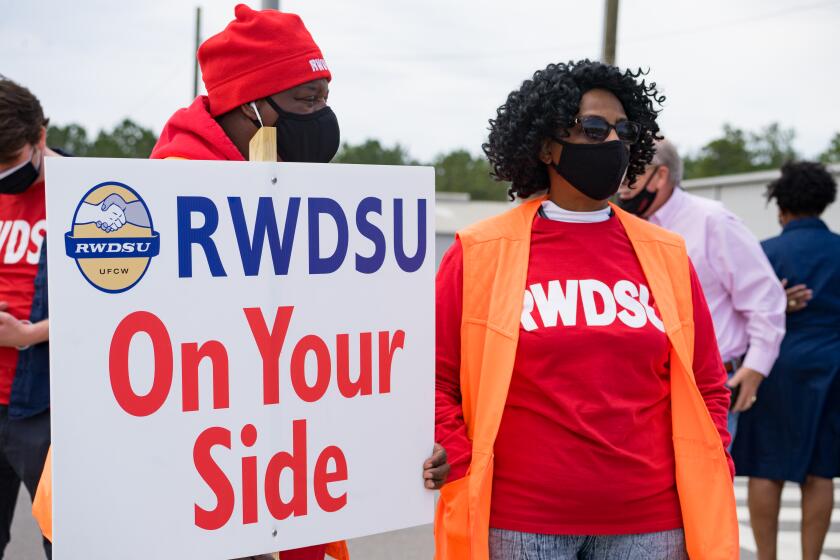

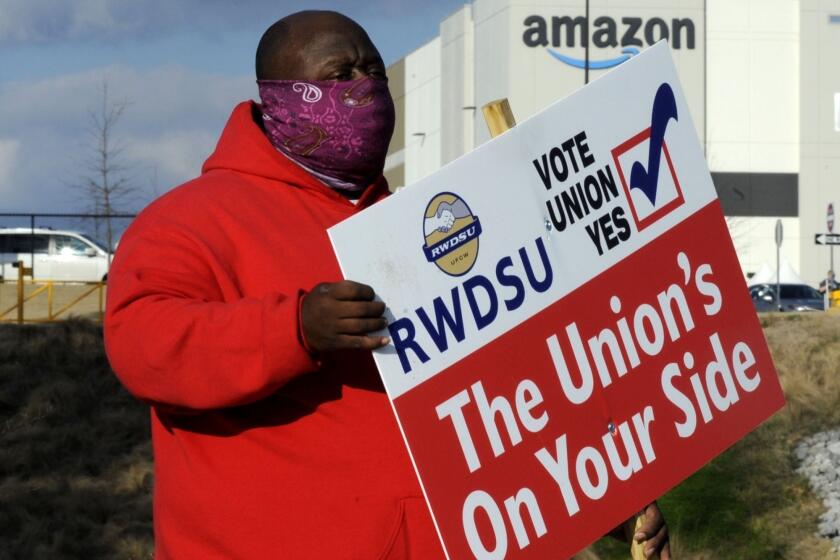

The challenge of organizing Amazon facility by facility became clear in April, when workers at its giant warehouse in Bessemer, Ala. voted 2 to 1 against representation by the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union after the company mounted intense resistance and the union gave up house-to-house visits due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Workers at an Amazon warehouse in Alabama are voting on whether to unionize, mounting the biggest challenge to the trillion-dollar retail company since it was founded.

The Teamsters, which had revenue of more than $200 million last year, declined to say how much it would spend or how many staffers it would devote to the Amazon project.

But even before Thursday’s vote, the Teamsters for several years has been quietly laying the groundwork for eventual future union elections at Amazon warehouses, said John Logan, director of labor and employment studies at San Francisco State University.

Given the scale of Amazon’s ambition in numerous industries, including logistics, groceries and healthcare, Logan predicted the Teamsters would join with other organized labor groups, such as the Service Employees International Union and the United Food and Commercial Workers, to mount a coordinated campaign.

“The Teamsters cannot do this alone,” he said. “It will take enormous effort and all the community and political support they can garner. But Thursday’s resolution shows they are genuinely serious.”

In an opinion piece in Salon this month, Korgan cited the Teamsters’ history of building worker power through shop floor work stoppages, citywide strikes and street demonstrations. “Building genuine worker power at Amazon will take shop-floor militancy by Amazon workers and solidarity from warehousing and delivery Teamsters,” he wrote.

The union already has begun to engage community groups, including in the Inland Empire, where Amazon, with 14 vast warehouses, is the region’s largest employer. In San Bernardino, Korgan’s local joined a coalition of environmental justice groups in an effort to force Amazon to slash truck pollution and raise wages at a new $200-million air cargo facility.

Amazon workers “face dehumanizing, unsafe and low-pay jobs, with high turnover and no voice at work,” Korgan said. “With today’s resolution we are activating the full force of our union to support them.”

Ben Reynoso, a San Bernardino City Council member, said the Teamsters vote may give “hope to workers who are seeking to unionize but have been discouraged from doing so by Amazon. It tells private employers you should be put on your toes — we’re coming for your employees to feel supported, empowered, and like actual humans.”

The Teamsters are ramping up advocacy for antitrust enforcement, labor policy reform and global solidarity aimed at Amazon.

Amazon workers in Bessemer, Ala., vote against unionizing. It is the closest Amazon workers anywhere in the U.S. have come to a union.

In California, a Teamster-backed bill, AB 701, is moving through the Legislature and would require warehouse employers to disclose quotas for the pace of work to employees and state enforcement agencies. The bill would prohibit employers from counting time that workers spend complying with health and safety laws as “time off task.”

“A UC Merced Community and Labor Center study found that warehousing had the highest increase in pandemic-related deaths of any industry in California, with a 57% increase in deaths last year,” the bill’s advocates wrote legislators this month.

“There is something deeply wrong with allowing mega-corporations like Amazon and Walmart to push their workers to a literal breaking point, just so customers can get next-day delivery,” said Assemblywoman Lorena Gonzalez (D-San Diego), the bill’s sponsor.

Amazon’s warehouse workers are classified as employees, but most of its delivery workers are employed by smaller contract companies, making the task of organizing them even more challenging.

“Amazon drivers earn about half of what a Teamster makes doing the same job, but with much inferior working conditions,” said Jake Alimahomed-Wilson, a Cal State Long Beach professor and coeditor of the book “The Cost of Free Shipping: Amazon in the Global Economy.”

If mobilizing Amazon workers seems daunting, however, Victor Narro, a longtime organizer and UCLA labor studies professor, cites several innovative Los Angeles union campaigns for nonunion low-wage workers. “Successful organizing efforts don’t happen overnight,” he said.

“The successful Justice for Janitors strike in 2000 was an outcome of strategies dating back to the mid-1980s. The CLEAN Carwash campaign began in April 2008. It was not until 2011 that we won the first major union contract for carwash workers in Santa Monica.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.