Column: For families of COVID victims, an agonizing wait for burials and paperwork

Roughly 600,000 Americans have died of COVID-19 — a tragedy of monumental proportions.

But spare a thought as well for the living. Specifically, family members and others tasked with burying the dead and putting the affairs of the deceased in order.

I hadn’t really thought about these challenges before speaking the other day with Christine Bramhall, whose brother, Robert Avila, died in February at the age of 76.

“Everyone assumes it was COVID,” the Culver City resident told me. “But I don’t know for sure. I don’t have the death certificate.”

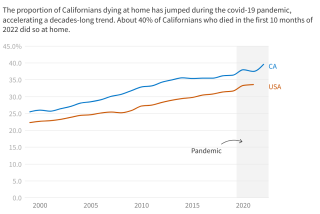

I don’t know how to say this delicately, so I’ll just say it: The massive death toll of the pandemic caused a traffic jam at cemeteries and mortuaries, and a months-long backlog in the issuing of death certificates.

This backlog, in turn, has rippled through society as bereaved families struggle to resolve the estates of loved ones without the documentation necessary to put matters to rest.

“After my brother died, I was told it would take two or three weeks to get his death certificate,” said Bramhall, 74, the executor of his will.

“That was four months ago,” she said, the emotion in her voice still raw.

Authorities say most of these logistical issues have been worked out. But delays persist.

A Highland Park man, who says he hasn’t smoked for 25 years, was told by Hertz to pay a $400 fee after workers claimed they smelled cigarettes.

Avila served in Vietnam. He was issued a Certificate of Achievement in 1967 for, in the words of his commanding officer, “a devotion to duty and pride of accomplishment rarely observed in others of similar experience, grade and time in service.”

But without a death certificate, Bramhall was unable to claim the benefits he’s owed as a veteran, including a headstone for his grave.

Avila worked for about 25 years as a teacher’s aide and athletic coach at John Marshall High School in Los Angeles.

He was remembered on Facebook by a volleyball player as “a generous and caring person who dedicated his heart and body to Marshall students.”

But without a death certificate, his sister was unable to access the pension money that Avila wanted to leave to a friend.

He intended for his car to be given to his caretaker. But the Department of Motor Vehicles wouldn’t transfer the registration without a death certificate.

“It’s been rough dealing with all this,” Bramhall said. “I’m not sleeping very well at night.”

In effect, her brother has spent months in bureaucratic limbo, dead but not dead, gone but not gone.

And what Bramhall is experiencing is by no means unique.

California’s insurance commissioner estimates average pandemic refunds to stuck-at-home drivers were about half what they should have been.

The staggering pandemic death toll overwhelmed resources in every state earlier this year, with bodies taking up all available space in funeral homes, mortuaries, coroner’s offices and hospital morgues.

Authorities had to repeatedly raise the limit on cremations permitted in Southern California as the number of stored bodies ran into the thousands.

“The capacity of the decedent management system, including hospitals, funeral homes, crematoria and the coroner’s office, is being exceeded,” Wayne Nastri, executive officer of the South Coast Air Quality Management District, said in an April executive order once again raising the cremation limit.

Things got so bad that, at one point, the California National Guard was called in to store bodies in refrigerated trucks.

After his death in February, Avila’s body was transported to Calvary Cemetery and Mortuary in East L.A. It was kept in storage for three months before a burial could be held in May.

Adrian Marquez Alarcon, a spokeswoman for the Catholic Church-run facility, said Calvary’s caseload increased by 50% earlier this year.

“Between February and March 2021, it was not uncommon for families to wait six to eight weeks for an appointment to make arrangements for a deceased loved one, and then another three to four weeks for the service,” she told me.

The situation is now improving, Alarcon said, and Calvary “is grateful to our patrons and families for their understanding during these difficult and unprecedented times.”

Bramhall said she accepted how challenging things had been for everyone. But that doesn’t make it easier for grieving families.

“You want to let go,” she said, “but you can’t.”

A Southern California fitness company called Pure Barre charges job applicants $1,800 for their training. That may be illegal under California law.

The clerical aspect of death — the issuing of documents attesting to a person’s passing — has taken a back seat to the more pressing concern of managing bodies and maintaining public health.

But our system grinds to a halt without such paperwork. Claims can’t be filed. Benefits can’t be processed. Records can’t be updated.

In the modern world, you aren’t officially dead until you have a piece of paper saying you are.

Death certificates in L.A. County are issued by the Death Section of the Vital Records office of the Department of Public Health.

A department spokeswoman said only that “at the height of the surge, we were delayed.” She added, “We caught up, and we are current now.”

A spokeswoman for the L.A. County medical examiner-coroner said the pandemic resulted in “longer times to process cases.”

“We held decedents at our facility for a longer time while some mortuaries worked to arrange for additional storage space at their locations,” she acknowledged.

Families and friends of those decedents, meanwhile, were unable to find closure amid the delays. The grieving process stretched into weeks and then months.

In any case, I’m glad to report that shortly after I got involved, Bramhall said she received a call inviting her to stop by the mortuary and pick up her brother’s death certificate.

“This will put things to rest,” she told me.

I asked what her brother would have made of all this.

Bramhall laughed for the first time.

“He’d have given me a sideways look and said, ‘Of course death is complicated.’”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.