Stevie Ryan seemed ready to break out of a rut.

Her pioneering work as an early YouTuber had led to a VH1 show, but “Stevie TV” was canceled after two seasons and Ryan subsequently struggled to chart a course in Hollywood. For a period, she had stopped going to auditions altogether.

In spring 2017, however, she recommitted to her career, telling her manager that she was ready to get back to work.

Around the same time, Ryan was also allegedly starting a new relationship — one with Gerald Baltz, a nurse practitioner who for two years had provided her with psychiatric care, issuing her prescriptions for several drugs used to treat mental health disorders.

“We just exchanged numbers and he had a meltdown over it being unethical,” Ryan texted a friend in April 2017, according to a legal document.

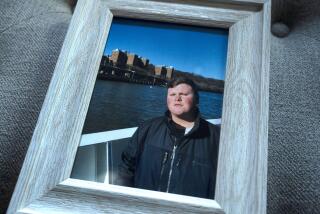

Three months later, Ryan took her own life. Her July 1, 2017, suicide at the age of 33 staggered her friends and family.

“You don’t expect to be making funeral arrangements for your daughter — that’s devastating,” said her father, Steve Ryan. “There’s just so many unanswered questions.”

Now, an ongoing legal proceeding brought by the head of the California Board of Registered Nursing against Baltz is revealing new details about Stevie Ryan’s final months.

Baltz is alleged to have engaged in an inappropriate, boundary-crossing relationship with Ryan while she was his patient, and then a sexual relationship with her while she was receiving treatment at the facility where he worked, according to a formal accusation filed against him with the nursing board in June 2020. The filing includes passages of text messages allegedly exchanged by Baltz and Ryan about their intimate encounters, and his instruction for her to delete the conversation.

Baltz also allegedly issued Ryan prescriptions for about 10 drugs used to treat a range of conditions — including depression, schizophrenia and bipolar disorder — without providing “clear rationale for prescribed medications,” according to the accusation. And he allegedly failed to seek supervision for her when she was suicidal.

“Saw my doc. He said DO NOT go to the hospital,” Ryan texted a friend in an undated message, according to the accusation. “He’s putting me on new meds AGAIN ... But he is so hot ... like FINE ... I think I’m dating my doctor now.”

Suicide prevention and crisis counseling resources

If you or someone you know is struggling with suicidal thoughts, seek help from a professional and call 9-8-8. The United States’ first nationwide three-digit mental health crisis hotline 988 will connect callers with trained mental health counselors. Text “HOME” to 741741 in the U.S. and Canada to reach the Crisis Text Line.

The accusation seeks the suspension or revocation of Baltz’s nursing licenses for alleged misconduct that is subject to disciplinary action under the California Business and Professions Code. It accuses Baltz of gross negligence and incompetence, among other allegations.

There is no public record of Baltz’s response to the accusation, which came after the nursing board, an agency within the state’s Department of Consumer Affairs, received a complaint in 2018 about his treatment of Ryan. However, during an interview with a nursing board investigator, Baltz, 47, said that he could not “clearly” remember Ryan nor recall what he had treated her for, according to the accusation.

The Times asked Baltz more than 25 detailed questions about the reporting in this article. In a written response, Baltz’s attorney, Melanie Balestra, said that she had advised him to not respond to the inquiry because he was bound by a “confidentiality statement” with the Board of Registered Nursing. The attorney said that the nursing board had made “absolute errors in their facts” but did not specify what she was contesting.

“There is no way that anyone can realize the amount of pain [Ryan] was in or what caused her to decide to take her life,” Balestra said. “To blame one person is unconscionable.”

A nursing board spokeswoman declined to answer questions about the case, explaining it “does not comment on pending matters.” A hearing in which Baltz will present a defense to the accusation is scheduled for Oct. 12 with the state’s Office of Administrative Hearings.

Baltz has continued to work as a nurse practitioner during the board’s years-long scrutiny of his actions. He is listed as the lone staff member on the website for Melrose Psych, a facility in the Beverly Grove neighborhood. Emails sent to Baltz late last month generated an automatic response that offered links to book appointments and explained that “all therapy/medication sessions will be done via telepsychiatry” due to the pandemic.

Friends and family of Ryan said they are speaking out for the first time in part because they’re worried for any patients Baltz may be treating.

“That’s what made me so furious — that he’s still practicing,” said Yuni Kim, a friend of Ryan’s. “She had ineffective ... healthcare.”

Some of the allegations disclosed in the accusation are similar to those contained in a wrongful-death lawsuit brought by Ryan’s parents against Baltz in 2018. He and his company, Baltz Psychiatry Nursing, settled the L.A. County Superior Court case for $200,000, according to a settlement notice filed with the court.

Steve Ryan said he learned about the details of his daughter’s relationship with Baltz only after her death.

“We know that she was vulnerable,” he said, “and [Baltz] took an oath ... to help and not harm. And I don’t think he helped at all.”

From YouTube to TV

Stevie Ryan grew up in Victorville, the high desert city 90 miles from Los Angeles. She came of age during the 1990s internet boom and developed a keen sense of what would — and wouldn’t — work on the web. As a preteen, Ryan hung out in chat rooms and learned how to use a video camera, according to a 2007 profile of her in The Times.

“Since I was young, I’ve been a total camera hog,” she said.

By her teenage years, Ryan harbored Hollywood dreams that she pursued with tenacity. When she was 18, she burrowed beneath a fence to sneak onto the set of a Moby music video, and wound up being featured in it, The Times reported. The experience inspired her to send head shots to talent agencies.

She was on the ground-floor level of people to get famous from YouTube … to launch it into a TV show. Back then, that was a major leap.

— Michael Pelmont, Stevie Ryan’s manager

Ryan moved to Los Angeles around 2005, the same year YouTube launched. It soon became her passion. In May 2006, she posted her debut video as Little Loca, a character that would turbocharge her career. Little Loca was a tough-talking 18-year-old from East L.A. who Ryan, a white woman, said was patterned after Latina high school classmates she admired.

She also released other types of videos, including short films in the style of silent movies set to ethereal piano music, but Little Loca attracted the most attention — and controversy. On YouTube, some commenters objected to Ryan portraying a self-described “chola.”

Ryan’s hometown newspaper, the Victorville Daily Press, wrote that her audience “was divided between those who got the bit and those who felt an outsider was propagating racial stereotypes.” But she seemed to court the outrage, saying in one video that those who didn’t like the fact that she was playing a Latina could “F— off.”

The popularity of the Little Loca character led to a New Yorker profile that positioned Ryan, then 22, as an innovator. At the time, YouTube was a different platform: Diary-like video series were in vogue, and a DIY aesthetic proudly reigned. Ryan, meanwhile, was focusing on storytelling and experimenting with form.

Soon, she was producing videos that got more than 1 million views apiece — a notable milestone in YouTube’s early days. And the entertainment industry came calling.

At a meeting with talent manager Michael Pelmont in 2010, Ryan made clear that her ambitions went far beyond online fame. “She said, ‘I want my own TV show,’” recalled Pelmont, who became Ryan’s manager. “She just went for it.”

Ryan got that show: “Stevie TV,” a VH1 sketch comedy program that marked a breakthrough in YouTube’s tastemaking ascent. “She was on the ground-floor level of people to get famous from YouTube … to launch it into a TV show,” Pelmont said. “Back then, that was a major leap.”

After two seasons and 14 episodes in all, VH1 canceled “Stevie TV” in 2014. The loss weighed on Ryan, her father said, and pursuing a more straightforward career as an actress didn’t jibe with her sensibilities. “She wasn’t really interested in becoming a character that somebody else made up,” he said.

In interviews with The Times, 12 people accused Magic Castle management, performers and others of abuses, as the legendary Hollywood club dedicated to the craft of magical performance wrestles with allegations and membership unrest.

After “Stevie TV,” Ryan went on her share of auditions, Pelmont said, but struggled with the process. And some projects she pursued never moved forward.

Pelmont worried about Ryan, whom he described as “just fearless, but at the same time petrified.”

That’s “a really hard dichotomy,” he said, adding that Ryan struggled to overcome her insecurity “for years and years.”

A changing relationship

In April 2015 — a little more than a year after “Stevie TV” was canceled — Ryan began receiving medical care from Baltz, according to the accusation.

At the time, Baltz, who goes by Jay, was about six years into his nursing career. A St. Louis native, he graduated from Brooklyn College in 1998 with a bachelor’s in fine arts in creative writing, according to his LinkedIn page. Later, Baltz turned to nursing, earning three degrees from Saint Louis University, including two at the graduate level, according to LinkedIn.

Baltz has four nursing licenses in California, each active through April 2023, including one that allows him to provide psychiatric-mental health care and two for operating as a nurse practitioner, according to filings with the state’s Consumer Affairs Department. He also secured nursing licenses in Colorado in 2018 and Washington in 2019, records show.

Aside from the Ryan accusation, there is no record of disciplinary or enforcement action against Baltz by any state agency that oversees nursing licensure.

Nurse practitioners have a unique and evolving role in the healthcare system. They are registered nurses with additional education, which affords them the ability to prescribe medicine, offer diagnoses and take a comprehensive role in a patient’s healthcare. In California, their activities currently require physician oversight — a stricter standard than in many states. Starting in 2023, however, California law will allow nurse practitioners to operate without oversight after working under supervision for three years.

The accusation alleged that Baltz’s care of Ryan violated the rules from the start. His intake note allegedly “provided scant information,” “failed to document” various elements of Ryan’s health history and “provided no clear documentation” for diagnosing her with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. The legal filing also claimed that Baltz “failed to include the formulation of the diagnosis or clear rationale” for medicines he prescribed her.

Baltz was supposed to be reviewing Ryan’s chart with his supervising physician. However, the physician — who was interviewed by a nursing board investigator but is not named in the accusation — “admitted he had not done chart reviews” with Baltz, according to the accusation. The physician also said that he had not completed other elements of his required oversight of Baltz and had last met with the nurse “a couple of years” prior, the legal filing said.

Loyola Law School professor Brietta Clark, an expert on healthcare law who reviewed the accusation at The Times’ request, said that “if the allegations are true, [Baltz] is somebody who was ignoring the rules.”

Baltz discontinued treatment of Ryan roughly two years into their practitioner-patient relationship. The change occurred after he had allegedly flirted with her and obtained her phone number while still serving as her care provider, according to the accusation, which establishes a timeline of events partly via Ryan’s medical records and text messages the nursing board investigator accessed on her mobile phone. (The legal filing does not refer to Ryan by name, instead using her initials; four people confirmed the “S.R.” in question is the late actress.)

In an April 5, 2017, message to a friend, Ryan said that she had asked her “doc” out, and that Baltz “agreed but ... she had to get a new doctor,” the accusation alleged. After that visit, Baltz referred her to another mental health provider at Insight Choices, the facility where he worked as an independent contractor, according to the legal filing.

Matt Stevens, an attorney representing Insight Choices, said the company was not aware of Baltz’s claimed conduct at the time it allegedly occurred and could not comment on the process of securing another provider for Ryan. Balestra said that Baltz had “properly referred [Ryan] out of his care to a psychiatrist who continued her treatment.”

Text messages allegedly sent by Baltz to Ryan on April 9, 2017, centered on the ethics of the situation. After Ryan asked Baltz if texting was unethical, he replied, according to the accusation, “I’m a healer, it would be unethical for me ... not you. I took an oath!!”

“If I did anything to harm you it would not only be a dick move but cause 10 years of school and work to disappear for me,” Baltz also texted Ryan that day, according to the accusation.

Ryan and Baltz discussed the details of their sexual liaisons in text messages sent over the course of the next week, according to the accusation. After an exchange in which Baltz apologized for biting Ryan, he urged her to delete the messages, the accusation alleged.

Saw my doc. He said DO NOT go to the hospital. He’s putting me on new meds AGAIN ... But he is so hot ... like FINE ... I think I’m dating my doctor now.

— Stevie Ryan, in a text message to a friend

Although Baltz stopped treating Ryan on the same day they allegedly agreed to go out, medical law experts who spoke with The Times said that the situation was troubling.

“They start a relationship and he’s still working at the same clinic and she gets treatment at the same clinic — that still strikes me as problematic,” said Dr. Julie Cantor, who until 2020 was a longtime lecturer on medical ethics and other topics at the UCLA School of Law, and reviewed the accusation at The Times’ request. “In terms of a treating relationship, those power dynamics are still in play.”

Baltz’s alleged intimate relationship with Ryan is cause for discipline under a section of the state business code related to “unprofessional conduct,” the accusation said. The code stipulates that such conduct includes “the commission of any act of sexual abuse, misconduct, or relations with a patient, client, or customer.”

National medical organizations universally condemn healthcare professionals having sexual relationships with current patients or clients, though only some take a stance on intimate contact with former care recipients.

The American Psychiatric Assn.’s medical ethics code is unequivocal: “Sexual activity with a current or former patient is unethical.” The American Psychological Assn. says that psychologists must wait two years after terminating treatment before engaging in an intimate relationship with a former client and cautions that if such contact is to occur, the medical professional would “bear the burden of demonstrating that there has been no exploitation.”

Meanwhile, the American Nurses Assn.’s code of ethics for all nursing professionals says that “dating and sexually intimate relationships with patients are always prohibited” but offers no guidance on relationships with former ones.

The Times found a rising number of death investigations across the country were complicated or upended after transplantable body parts were taken before a coroner’s autopsy.

While reporting this story, The Times reviewed an alleged text message conversation between Baltz and Ryan that began after he stopped treating her and spanned much of April 2017. The texts were provided by a former boyfriend of Ryan’s who is noted in the legal filing as having made the 2018 complaint to the nursing board about Baltz. This person, who asked not to be named over his own privacy concerns, showed The Times email correspondence indicating the same text messages were sent to the nursing board investigator.

In the conversation — sections of which are cited in the accusation — Baltz weighed in on Ryan’s medical care when she complained about side effects from medication. “Changing meds can cause people to feel weird for a few weeks that’s normal,” he texted. When Ryan mentioned her depression, Baltz said, “You need to magnetize your brain,” an apparent reference to transcranial magnetic stimulation treatment she received at Insight Choices, according to the accusation.

Baltz also repeatedly voiced worries over dating Ryan, texting: “I do feel a strong connection and feel guilty at the same time,” and later saying that he hoped she would “never say anything.”

As their relationship appeared to sour, Baltz wrote: “I made a horrible error in judgement. You needed help and I worsened the situation.”

By late April 2017, Ryan seemed ready to break up with Baltz. Kim provided The Times with a text message conversation she said she had with Ryan on April 23 in which they discussed the end of the relationship. In the messages, which Kim said she also gave to the nursing board investigator, Ryan explained that she told Baltz via text message, “I don’t feel like texting any more.”

“Even though I don’t like him I feel super bad,” Ryan told Kim, who said she knew the relationship was inappropriate and supported her friend’s decision to end things with Baltz.

Ryan also shared with Kim screen grabs of her breakup text conversation with Baltz, including one in which he said: “So you don’t want to date anymore? It’s okay I figured you might not be thinking clearly. That sucks I like you but if that’s what you’re saying I’ll leave you alone.”

During his interview with the nursing board investigator, Baltz said “he could not recall if he ever sent text messages to” Ryan, and denied he’d written ones shown to him, according to the accusation. However, it also said that Baltz confirmed his cellphone number, which matched his contact information in Ryan’s phone; and, when prompted, he showed the investigator a tattoo on his clavicle that was identical to one seen in a photograph from the text conversation.

A few days after the breakup, Baltz texted Ryan to ask her whether she’d be doing transcranial magnetic stimulation treatment at Insight Choices, according to the accusation.

“F— it I’m not doing it. It’s too much drama,” Ryan replied, according to the accusation. Baltz allegedly then wrote: “Listen I feel terrible about this whole thing. Most important thing is your mental health. This is exactly why I’m an idiot.”

Kim said that Ryan wound up continuing transcranial magnetic stimulation treatment at Insight Choices. But she soon stopped because of Baltz’s presence there, added Kim, who said that, at the time, she didn’t know the details of her friend’s medical issues.

Asked about Ryan’s transcranial magnetic stimulation therapy, Stevens, the attorney for Insight Choice, said, “We do not comment on patient treatment.”

During Baltz’s interview with the nursing board investigator, the nurse allegedly “admitted that he was aware that S.R. had suicidal thoughts,” according to the accusation, which used Ryan’s initials. “When S.R. was suicidal, [Baltz] did not refer her to a higher level of care, did not send her to the emergency room, and did not conduct an in-depth suicide assessment or crisis plan,” the legal filing claimed, without saying whether Baltz’s alleged inaction occurred while he was treating Ryan or after their practitioner-patient relationship ended.

California law obligates nurses who observe “abnormal characteristics” in patients to initiate “appropriate reporting, or referral” to others in the medical field.

However, according to state law, a medical professional’s duty to a patient can end once he or she terminates that working relationship, provided certain requirements are met, such as giving the patient reasonable time to find another healthcare provider. Still, per case law, even after a treatment relationship appears to have ended, subsequent contact between a health professional and former client — such as a practitioner offering medical advice — could resurrect the prior patient-provider relationship, and the duty that comes with it.

“If they are continuing any type of interaction back and forth, then the nurse opens himself to the possible finding that there was a continuing treatment relationship,” said Clark, the Loyola law professor. “There is a reason we regulate so strictly any sexual relationships between patient and practitioner, especially in the mental health arena, because [intimate contact] really does alter ... the dependence of the patient on the provider.”

Ryan’s final months

Although Ryan’s Hollywood career had stalled out after the cancellation of “Stevie TV,” there were signals in 2017 that she was ready to make a change.

After having refused to go on auditions, Pelmont said, Ryan reached out to him in the spring of that year to say she was ready to get back to work.

And she had other projects, including a podcast with a friend, comedian Kristen Carney.

With a focus on depression, “Mentally Ch(ill)” debuted April 4, 2017. Over the course of 11 episodes, the podcast covered topics including Ryan going off of Prozac “cold turkey” and her transcranial magnetic stimulation treatment.

Discussing self-confidence, Ryan seemed to suggest she could turn a corner. “I know what I am capable of doing,” she said on the show. “I’ve been a badass bitch before — and I know I can be a badass bitch again.”

In her final appearance on the podcast, Ryan tearfully talked through the then-recent death of her grandfather. “I am just worried that this is going to send me into a deeper depression,” she said.

Three days after the episode was released, Ryan killed herself.

“She was tough on the outside,” Carney said, “but it was only because she was so vulnerable on the inside.”

A little less than a year after Ryan’s suicide, her parents filed the wrongful-death lawsuit against Baltz; his company, Baltz Psychiatry Nursing; and Insight Choices, which he left a month after Ryan died. Unlike the accusation, the 2018 lawsuit alleged that Baltz engaged in sexual contact with Ryan while she was his patient, among other claims.

There is no record in an online legal database of Baltz’s response to the allegations. In a court filing, Insight Choices denied the claims; it also said that any injuries, damages or losses allegedly suffered by Ryan’s parents were caused by “persons separate and apart from this answering defendant.”

Baltz’s settlement with Ryan’s parents was paid by his professional liability insurance carrier, according to the nursing board accusation. After the settlement agreement, the case was dismissed against Baltz and his company in March 2019, according to court documents.

The claims against Insight Choices were dismissed in May 2019, records show. Stevens, who said that the company’s management learned of Baltz’s alleged sexual contact with Ryan only after the lawsuit was filed, noted that the case “was dropped without any settlement or payment by Insight Choices.”

“We uphold the highest standard for our providers and adhere to community standards as well as federal, state, and local statutes,” Insight Choices said via Stevens. “Any deviation from the law or community standards are reviewed and corrected quickly.”

Ultimately, Steve Ryan said, he pursued the lawsuit because he hoped Baltz would “lose his license” over the matter. Such an outcome is possible in the nursing board action.

Some who were close to Stevie Ryan expressed unhappiness over the pace of the proceeding, which has been in process since summer 2018.

Asked about the delay, the nursing board’s spokeswoman said it “is engaged in continual efforts to improve processing timelines,” without providing details on the specifics of Baltz’s case.

The board has in the past been criticized for moving slowly in such matters. After The Times and nonprofit news organization ProPublica reported in 2009 that it took an average of three years and five months for the agency to close complaints brought against nurses, then-Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger fired half of the nursing board. The issue has endured: In 2016, for example, a review of the nursing board by the California state auditor’s office found that “significant delays” in the complaint resolution process had allowed some nurses who could be a risk to patients to keep practicing.

The nursing board’s spokeswoman said the agency had addressed all the recommendations in the auditor’s report, adding that it “is always interested in identifying opportunities to better fulfill its mission of protecting California consumers.”

While Steve Ryan awaits the outcome of the nursing board proceeding, he worries about any clients Baltz may be treating. He harbors some discomfort over the thought of potential repercussions for the nurse practitioner, but, more than anything, Ryan wants a measure of justice for his daughter.

“I don’t want to ruin somebody’s life,” he said. “But ... at least he’s got a life to ruin.”

Times researcher Scott Wilson contributed to this report.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.