Column: The competing economic visions of Biden and Trump — one looks ahead, the other back

In this election cycle, it’s tempting to see every aspect of American life in partisan terms, including its economic divide. But there’s an aspect to the economic picture that doesn’t get enough attention despite the impulse to view everything through a red versus blue prism.

It’s not merely the split in manufacturing versus service or information sectors often noticed by analysts, with Trump and the Republicans favoring the former and Democrats — Hillary Clinton in 2016 and Joe Biden in 2020 — the latter. Rather, it’s the split between economically productive versus relatively unproductive areas.

None of Trump’s promised relief has been delivered on. The manufacturing revival has not materialized. Training for working people never happened.

— Mark Muro, Brookings Institution

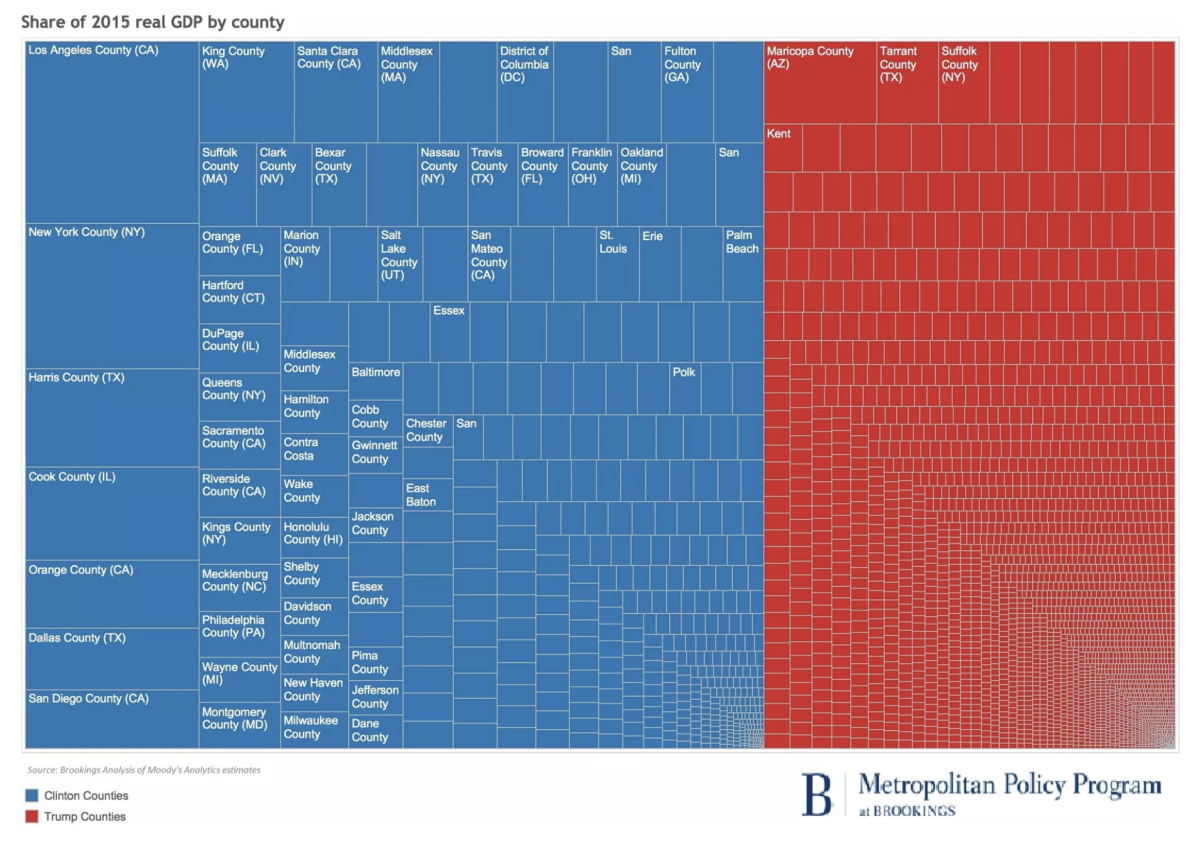

The divide could be seen clearly in the aftermath of the 2016 election. Mark Muro and Sifan Liu of the Brookings Institution observed then that “no election in decades has revealed as sharp a political divide between the densest economic centers and the rest of the country.”

To put it in raw numbers, Muro and Liu determined that the 487 counties won by Clinton produced 64% of America’s economic activity (measured by 2015 gross domestic product). The more than 2,600 counties won by Trump generated only 36% of GDP.

Most of the nation’s most economically weighty counties went for Clinton, with the exception of Maricopa County, Ariz. (Phoenix); Tarrant County, Texas (Fort Worth); and Suffolk County, N.Y. (a suburb of New York). Clinton swept the most economically important counties of California, including Los Angeles, Santa Clara, Orange and San Diego.

With the political world deeply focused on the question of whether the Trump administration comprises a gang of Russian pawns, less attention has been devoted to more mundane questions, such as what ever happened to Trump’s economic policy?

The GDP gap appears to have widened. Muro’s data show that by 2018, the counties that voted for Hillary Clinton in 2016 had increased their share of GDP to 66%, while Trump counties slipped to 34%.

Democratic strength in the largest counties has been growing since 1988, when Republican George H.W. Bush won 57 of the 100 largest counties. Four years later, Bill Clinton won 73. Barrack Obama won 88 and 86 of those counties in 2008 and 2012, and Hillary Clinton 88 in 2016.

Reducing these statistics into a forecast for the upcoming election, however, isn’t a simple matter.

“That part of America may not be the most productive,” political analyst John Judis told me, referring to the less economically productive regions, “but it’s still extraordinarily numerous. Because of the electoral college, it’s extraordinarily important.”

The economic divide, however, does provide a guidepost to the campaign strategy of Trump and the GOP.

As my former colleague Ron Brownstein, now at the Atlantic, observed recently on Twitter, California embodies 21st century America far more than Trump’s base does: “The GOP instinct to denigrate CA only underscores how Trump is walling it off from modern US & making it even more reliant on places/voters most hostile to change.”

Trump built his 2016 strategy around a direct appeal to voters in the industrial and agricultural heartland. A key element of that strategy was an overt attack on globalization, specifically on China, which many voters in those sectors saw — not without reason — as having stolen American jobs.

“Trump told us back in 2016 and has told us since that he’s running as a champion of the so-called forgotten Americans,” says Alan Tonelson, an economic researcher who has worked for organizations of small and midsize businesses.

“By that phrase,” Tonelson says, “he means those Americans who for a wide variety of reasons — trade policy mistakes being one of them — who have been left behind for however many decades you want to go back.”

The economic rationale for President Trump’s trade war with China has been so threadbare and the likelihood of losses so great that no one should be surprised that it hasn’t been the success Trump predicted.

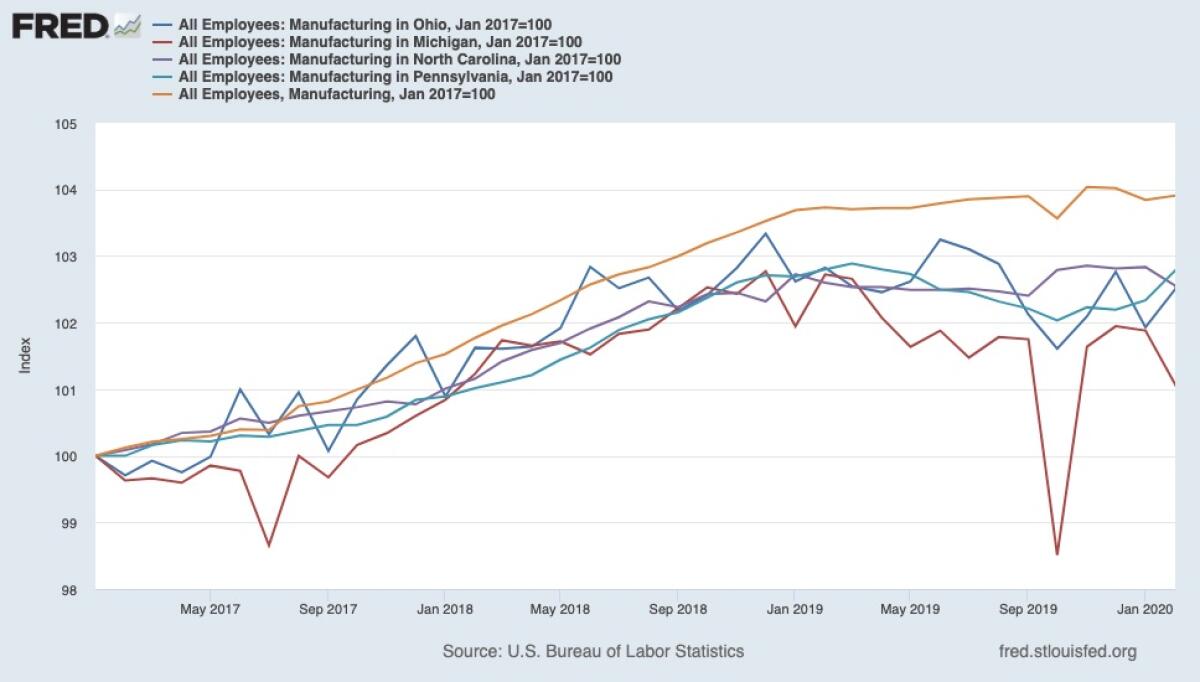

Whether Trump can put this strategy to work again this year depends partially on whether voters believe him. Hard numbers show that he has largely failed to make good on two key promises to the 2016 electorate — to bring manufacturing jobs back from abroad and revive coal employment.

In truth, overall manufacturing added about 497,000 jobs nationwide in the three years between Trump’s inauguration and the onset of the coronavirus outbreak in February, bringing total employment to 12.9 million, a gain of about 4%.

That’s better than the gain of about 2.3% in the last three years of Obama’s term, but hardly an epochal gain; nor has it brought U.S. manufacturing employment anywhere back to the more than 13 million manufacturing jobs that existed before the 2008 recession.

In politically important swing states, moreover, Trump’s pre-pandemic job creation performance lags that of the last years of the Obama presidency, according to an analysis by the worker advocacy group Raise America’s Pay. In Florida, Trump has created 260,000 fewer jobs than Obama in that period, in Michigan 120,000 fewer, and in Wisconsin, 50,000 fewer.

Trump has obscured this reality through a lavish helping of misrepresentations and outright lies. During a Sept. 10 rally outside Saginaw, Mich., Trump said, “We brought you a lot of car plants ... and we’re going to bring you a lot more.”

In fact, as the Detroit Free Press reported, only one new auto assembly plant has been announced for the state during Trump’s term.

Even before the pandemic, the Free Press calculated, manufacturing employment in Michigan had grown only by about 1% during Trump’s tenure, compared with a gain of nearly 15% during Obama’s second term. Auto and auto parts manufacturing had actually shrunk by about 2,400 workers between Trump’s inauguration and the onset of the pandemic.

Tonelson says there’s evidence that Trump voters in swing states have gained more under Trump than is commonly assumed. He analyzed economic data for 203 of the 206 counties that had voted for Obama twice and then flipped for Trump. (Data weren’t available for the other three.)

In 130 of those counties, Tonelson found, “average annual salaries rose faster during the two years Trump has been in office than during the last two Obama years.”

His conclusion: “The claim that much of the Trump electorate had been fooled by phony populist promises doesn’t look very strong, at least based on this data.”

State and federal statistics released as recently as Friday make it clear: California is smoking hot, economy-wise.

Still, many economists and industrial experts viewed Trump’s 2016 promise of massive job gains in manufacturing as impossible to deliver. Employment in U.S. manufacturing had peaked in 1979 at about 19.5 million.

Employment bottomed out in early 2010 at about 11.5 million, down by more than 40%. In the ensuing years it crept back up to about 12.8 million, but the pandemic eradicated most of those gains, at least for the moment.

What makes it particularly hard to recover all those lost jobs is that American industry has remade itself into a more efficient, low-employment powerhouse.

“The total inflation-adjusted output of the U.S. manufacturing sector is now higher than it has ever been,” Muro of the Brookings Institution wrote just after the 2016 election. That was true even though manufacturing employment “remains near the lowest it’s been.... Labor is being increasingly done by robots.”

The structural realities of the coal business similarly made Trump’s promises to coal workers fantastical. Coal employment in the U.S. peaked in 1975 at about 175,000.

But the shift in energy consumption to cleaner fuels, including natural gas and renewables, had reduced employment to about 51,000 by Trump’s inauguration. It has fallen as low as 42,000 since then.

“None of Trump’s promised relief has been delivered on,” Muro told me. “The manufacturing revival has not materialized. Training for working people never happened. Trade relief is very blurry.”

Trump’s evisceration of labor protections will continue under Labor Department nominee Scalia

Whether Trump can still claim preeminence as a China-basher is open to question, Muro suggests. “Concern about China is now a bipartisan issue. Maybe it’s Trump’s most popular stance, but I don’t think he has any ownership of it.”

Layered on top of that record is the new factor of the coronavirus pandemic. In its latest stages, the crisis has evolved from a blue-state to a red-state phenomenon.

In July and August, 17 states recorded more than 1,000 new cases of COVID-19 per 100,000 residents. Two were blue states (California and Nevada) but the other 15 states had voted for Trump in 2016, including the electorally crucial states of Texas, Florida, Arizona and Iowa.

As of March 31, the pandemic’s “hot spots” — counties with 100 cases or more per 100,000 residents — had voted for Hillary Clinton by 62% versus 34% for Trump. By May 31, the balance had swung over — 49.7% had voted for Trump, compared with 43.9% for Clinton.

“Now the major economic factor of the last four years, which is the coronavirus, is being more intensely visited on those voters,” Muro says.

How these factors will manifest themselves in the election is still the subject of guesswork. There’s no question that Trump has aimed his campaign at an electorate that may still feel disaffected by economic conditions — though they may start to blame Trump for not fixing them as he promised.

Democrats appear to have maintained or even augmented their strength in what Judis calls “places driven by the production of ideas.” The two parties and their candidates are battling not merely over policy but their competing visions of where the American economy goes from here.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.