Nvidia buys SoftBank’s Arm for $40 billion in biggest chip deal

Nvidia Corp. said it agreed to buy SoftBank Group Corp.’s chip division Arm Ltd. for $40 billion, taking control of some of the most widely used technology in electronics in the semiconductor industry’s largest-ever deal.

Nvidia will pay $21.5 billion in stock and $12 billion in cash for the British chip designer, including a $2-billion payment at signing. Softbank may receive an additional $5 billion cash or stock if Arm’s performance meets certain targets, the companies said Sunday in a statement. An additional $1.5 billion in Nvidia stock will be paid to Arm employees.

The initial payment to SoftBank is a small premium over the $31.4 billion the Japanese company paid to acquire Arm in 2016, previously the semiconductor industry’s biggest deal. SoftBank is expected to own less than 10% of Nvidia after the transaction, according to the statement. Regulatory approval may take as long as 18 months before the transaction is completed and the deal needs sign-offs from Britain, China, the European Union and the U.S., the companies said.

In a move to placate Arm’s powerful customers and defuse regulatory concerns, Nvidia said the company will “continue to operate its open-licensing model while maintaining the global customer neutrality that has been foundational to its success.” Nvidia will add its technology to the offerings licensed by Arm, the Santa Clara, Calif., company said.

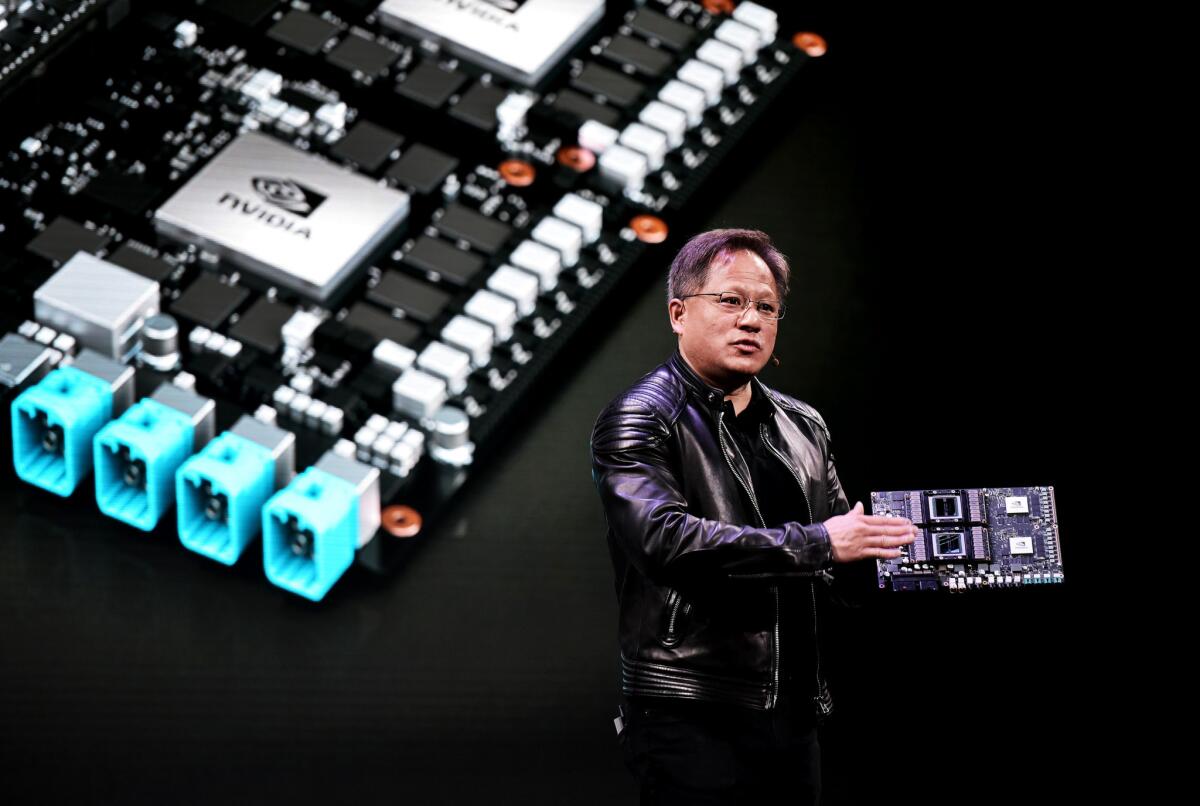

Nvidia Chief Executive Jensen Huang said he loves Arm’s business model and wants to expand its broad client list. As for concerns the deal will upset Arm’s relationships with customers including Apple Inc., Huang said Nvidia is spending a lot of money on the acquisition and has no incentive to do anything that would cause clients to walk away.

Under Huang, Nvidia has risen rapidly up the ranks of technology companies in market value and influence. Already the dominant force in graphics chips that make video games more realistic, Nvidia has carved out a slice of the market for data center chips and is moving into self-driving vehicles.

Arm’s importance far outweighs its revenue, which comes from licensing chip fundamentals and selling processor designs. Its technology is at the heart of the more than 1 billion smartphones sold annually. Chips that use its code and its layouts are in a wide variety of things, including factory equipment and home electronics.

The acquisition is fueled by the drive to bring artificial intelligence to everything that has an on switch. Having succeeded in selling Nvidia’s graphics chips to owners of data centers to speed up image recognition and language processing, Huang is looking to make sure his technology helps spread that to self-driving vehicles, smart meters and other products.

“It’s a company with reach that’s just unlike any company in the history of technology,” Huang said in an interview. “We’re uniting Nvidia’s leading AI computing with Arm’s vast ecosystem.”

Arm, with headquarters in Cambridge, England, has carved out a successful niche for itself by being independent. Fierce rivals such as Samsung Electronics Co., Apple, Qualcomm Inc., Broadcom Inc., Intel Corp. and Huawei Technologies Co. are all licensees. They either use Arm’s designs as the basis of their own chips or license its instruction set, the fundamental code used by processors to communicate with software, for proprietary efforts.

The acquisition by Nvidia, also a licensee, is a challenge to that neutrality. SoftBank’s purchase four years ago went ahead largely uncontested because the Japanese company wasn’t a competitor to any of Arm’s customers.

One customer that will be directly challenged is Intel. Huang said a priority will be investing in Arm’s efforts to design chips for data center computing. Although he’s carved out a $3-billion niche in the business of supplying Alphabet Inc.’s Google and Facebook Inc. with graphics processors that help with their artificial intelligence workloads, Huang said he wants to speed up the adoption of Arm-based central processors, or CPUs. That’s a lucrative market dominated by Intel, which has about a 90% share.

Nvidia announced it will keep Arm’s headquarters in Britain and will invest in a new facility there to push forward research in artificial intelligence, educate customers and provide a place for experimentation in robotics and automation. Huang said that commitment demonstrates how the acquisition will add to Britain’s technology footprint rather than detract from it.

SoftBank’s sale of Arm unwinds another strategic investment in favor of boosting liquidity and enabling founder Masayoshi Son to focus on the more tactical investing he has said he wants to pursue.

Nvidia’s Huang runs a company that’s captured the attention of investors like few others in the last decade. Like Son, he’s a charismatic leader espousing a long-term vision of where technology is headed. The Taiwan-born entrepreneur is more engineering focused than his Japanese counterpart, though, and often publicly delves into the minutia of semiconductor and computer science.

His latest successful recasting of Nvidia’s technology involves the processing of artificial intelligence work done in data centers. His chips are among the best at breaking up the manipulation of data into small pieces and then executing that in parallel at high speed.

Huang will also get a large footprint in the mobile industry and smartphones. A previous attempt by Nvidia to break Qualcomm’s dominance of that business failed. The biggest rival to Qualcomm in smartphone processors is Apple’s own internal effort. Those two companies are among Arm’s biggest customers.

Even without a presence in mobile, Nvidia’s value has soared in the last decade. Its shares, which ended 2010 at $15.42, closed Friday at $486.58. That’s given it a market value of just more than $300 billion, almost $100 billion more than Intel, the world’s largest chipmaker with seven times the revenue of Nvidia.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.