Column: Trump hasn’t done anything to bring down drug costs. You’re paying the price

If the Republican National Convention is any guide, you’re going to be hearing a lot in the next two months about how President Trump has brought down drug prices.

“Now, I’m really doing it,” Trump said on Day 1 of the RNC last week.

It wasn’t the first time he patted himself on the back for fighting Big Pharma.

“Drug prices are coming down, first time in 51 years because of my administration,” he said in May 2019.

None of this is true, as has been pointed out in recent days by economist Dean Baker of the Center for Economic and Policy Research and Kevin Drum of Mother Jones, and over the longer term by hard data compiled by the Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Drug prices are coming down, first time in 51 years because of my administration.

— President Trump, lying about his work on drug prices

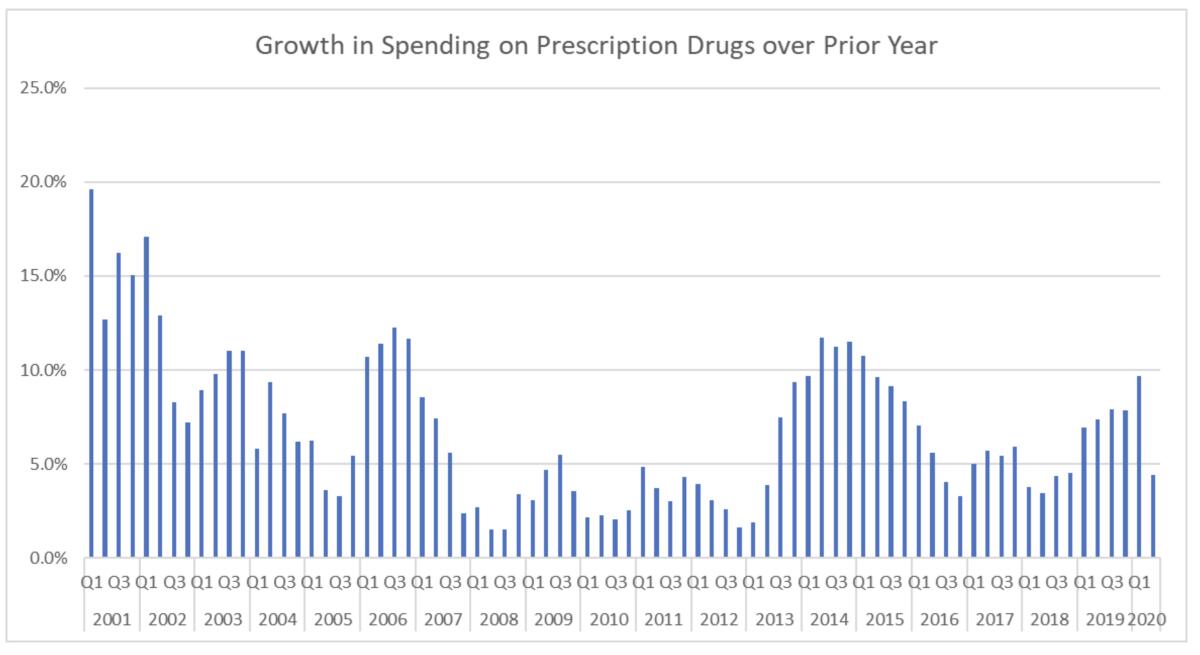

The truth is that prescription drug spending in the U.S. has risen almost inexorably throughout Trump’s term, generally at a faster pace than during President Obama’s first term and toward the end of his second term.

The pace of increase dropped sharply in the second quarter this year ended June 30, but that’s an artifact of the pandemic, during which many Americans have deferred routine doctor visits. But drug spending increased nevertheless, by 4.1% over the same quarter a year ago.

Prescription drug spending reached an annual rate of $497.8 billion in the first quarter, up by about 21.7% from the $409.1-billion annual rate in the first quarter of 2017, the start of the Trump presidency.

In sum, Trump hasn’t done anything to rein in drug prices. He has obscured that fact with his usual miasma of misrepresentation and misstatements, abetted by a drug industry that has been happy to go along with the subterfuge.

No one should be surprised at the lack of progress.

Trump’s secretary of health and human services, Alex Azar, is a former lobbyist for the drug company Eli Lilly and a former president of its U.S. operations. During his tenure at Lilly, the company tripled the price of its top-selling insulin product and was fined by Mexico for colluding to fix prices that the government paid for insulin.

Let’s start with Trump’s most recent claim, and work backward.

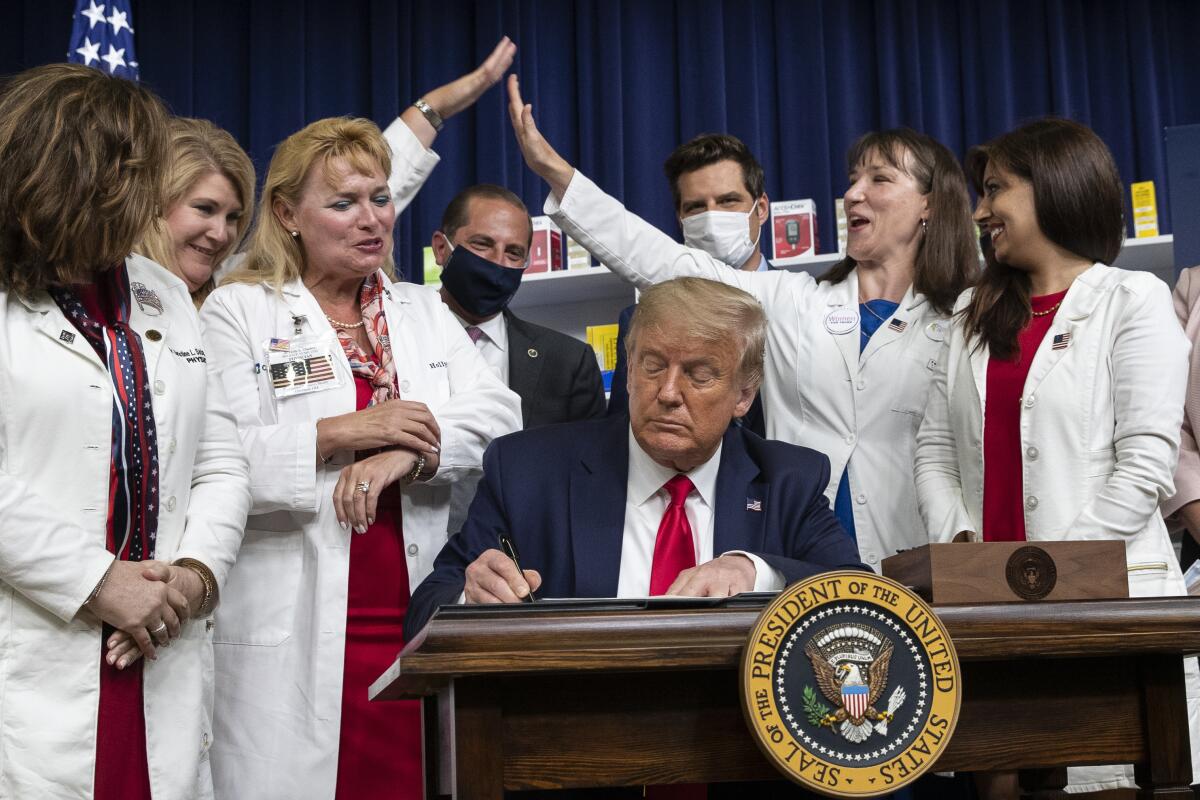

Trump’s convention reference was to a sheaf of executive orders he signed July 24.

A Democratic measure could cut drug prices by hundreds of billions of dollars, but can it pass?

One of the four orders would forbid drug company rebates on drugs for Medicare members to go to pharmacy benefit managers or health plans that negotiate discounts. Instead, the rebates would have to be passed on to the enrollees themselves.

The problem with such a rule, the Congressional Budget Office has pointed out, is that it would drive Medicare premiums higher.

For many members, especially those who use few prescriptions or drugs without large rebates, the increase in premiums would outstrip the savings from the rule. In other words, the rule would impose higher costs on members and on the federal government, which subsidizes Medicare premiums.

Trump’s executive order mandates that implementing the rule can’t increase federal spending, Medicare premiums or total out-of-pocket costs. But that just means the rule would be impossible to implement.

A second order would require government-sponsored dispensaries, generally in rural areas, to make insulin and epinephrine available to low-income patients without health insurance or with high co-pays. But those dispensaries already offer those drugs effectively for free to patients under the poverty line, so the rule’s impact would be minimal.

A third order would allow more Americans to import drugs from Canada, where the prices on many pharmaceuticals are lower than in the U.S. But there’s no guarantee that American buyers can access those lower prices, since Canada and the drug companies have made clear they’ll take steps to protect their own markets.

The giant drug company Pfizer seemed to hand President Trump a big win Tuesday when it announced it would roll back a slate of price increases that took effect July 1.

Then there’s the fourth order, which Trump called “the granddaddy of them all.”

It’s also the murkiest. Purportedly, it would tie Medicare prices for certain drugs to the best prices obtained in some foreign countries, a concept known as most-favored-nation status. But the rule would apply only to drugs administered in doctors’ offices, such as intravenous cancer drugs, not to prescription drugs bought from a pharmacy.

The full text of this order hasn’t been released. Trump originally said he would hold it back until Aug. 24 to give Big Pharma a chance to stave it off by coming up with “something that will substantially reduce drug prices.”

He said he had scheduled a meeting with drug executives for July 28 to hear their views, but that never happened. As my colleague David Lazarus reported on the deadline day, the industry eventually came up with a counter-offer to cut Medicare prices on some doctor-administered drugs by 10%. This wouldn’t even qualify as a “modest proposal.”

Basically, then, Trump’s trumpeted executive orders amounted to a smidgen more than nothing. That extended the pattern of Trump action on drug prices seen from the inception.

It will be remembered that Trump launched his drive on drug prices in 2018 by ostensibly jawboning Big Pharma into rolling back price hikes imposed as of July 1. “Great news for the American people,” he crowed on Twitter.

Sadly, no. As we observed at the time, this was nothing but a sop to Trump. The giant drug company Pfizer, for example, made clear that it wasn’t “rolling back” any increases — it was “deferring” them — temporarily.

“The company will return these prices to their pre-July 1 levels as soon as technically possible,” the company said.

Merck, to take another example, said it would lower the price of its hepatitis C treatment Zepatier by 60% and cut prices on six other drugs by 10%. Merck also pledged to not increase the average net price of its overall product portfolio by more than the inflation rate annually.

This was another head-fake. Zepatier was an also-ran among hepatitis C cures, with sales so low by the first quarter of 2018 that Merck listed its U.S. sales in its quarterly disclosures as zero. The other six drugs faced stiff competition from generic versions, and by some estimates accounted for less than 0.1% of Merck’s $40 billion in annual sales.

Merck’s pledge to hold the average net price of its portfolio to the inflation rate opened the door to its imposing steep price hikes on the drugs that mattered to its bottom line, while cutting prices on drugs that didn’t matter.

It’s hard to believe that anyone was taken in this summer when a handful of drug companies announced rollbacks of price increases or price freezes on some of their drugs, ostensibly in response to jawboning by President Trump.

Anyway, as soon as everyone’s attention shifted elsewhere, the drug companies rolled back the “rollbacks.” By December, Pfizer and Merck said they were moving ahead with price increases.

While this was going on, Trump, Big Pharma and Senate Republicans were stifling a proposal that really could have achieved something. This was a measure sponsored by House Democrats in 2019 and named after Rep. Elijah Cummings (D-Md.), a long-term foe of high drug prices.

The measure would require Medicare to negotiate prices for at least 25 of the most-prescribed drugs every year, starting in 2021, for Part D, the Medicare prescription program. The target drugs would be drawn from the list of 125 drugs with the highest spending in Part D and the commercial market.

The negotiated price couldn’t be higher than 120% of the average cost for the given drug in Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Japan and the United Kingdom. Most critically, the proposal would impose a stiff excise tax of as much as 95% on companies that refused to negotiate. That would keep them at the table.

Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) declared the bill dead on arrival. “Socialist price controls will do a lot of left-wing damage to the healthcare system,” he said.

See how this works? Trump and the GOP are all-in on proposals that aren’t serious and won’t work, but erect a brick wall against those with potential.

The result is that the drug industry sits back as the money rolls in, at your expense. Economist Baker observes that spending on prescription drugs actually increased “somewhat more rapidly under Trump than Obama-Biden, rising at a 6.3% annual rate under Trump compared to a 5.5% rate under Obama-Biden.” (He didn’t count the most recent quarter, affected by the pandemic.)

That won’t keep Trump from continuing to claim that he has held Big Pharma to account. But it should keep you from believing him.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.