Column: In GOP plan, you can’t sue your employers for giving you COVID — but they can sue you

If you were looking for evidence that Republicans in Congress have no sympathy for workers facing illness or worse from the COVID-19 pandemic, look past the party’s proposal to cut unemployment benefits.

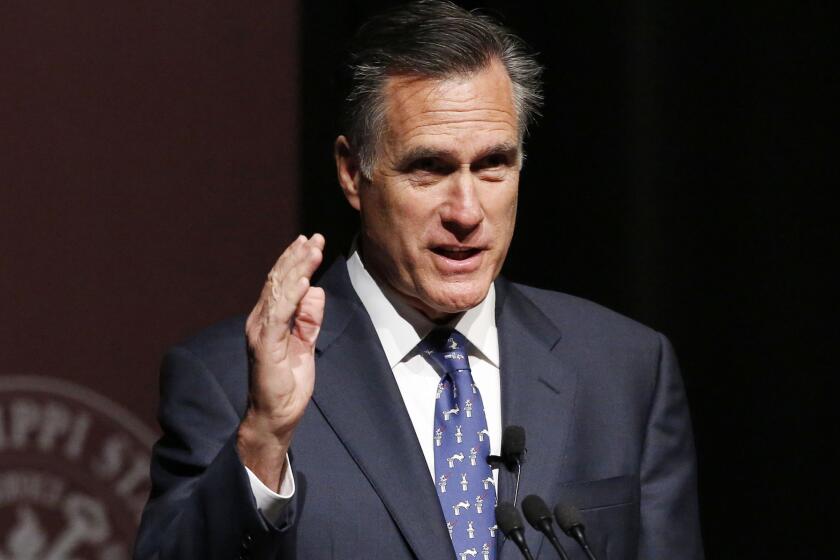

Instead, focus on the provision in its coronavirus relief bill that Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) calls a must-have in any bill that passes: liability protection for employers whose employees get sick at work.

This proposal has received scant attention in coverage of the GOP plan. But it’s more vicious than you could possibly imagine.

Ensuring that workers and consumers can hold companies accountable for their actions is critical to establishing a safe reopening of our economy.

— Celine McNicholas and Margaret Poydock, EPI

The GOP proposal would erect almost insurmountable obstacles to lawsuits by workers who become infected with the coronavirus at their workplaces.

It would absolve employers of responsibility for taking any but the most minimal steps to make their workplaces safe. It would preempt tough state workplace safety laws (not that there are very many of them).

And while shutting the courthouse door to workers, it would allow employers to sue workers for demanding safer conditions.

This is the provision that McConnell has described as his “red line” in negotiations over the next coronavirus relief bill, meaning that he intends to demand that it be incorporated in anything passed on Capitol Hill and sent to President Trump for his signature. The provision would be retroactive to Dec. 1, 2019, and remain in effect at least until Oct. 1, 2024.

The GOP proposal would make workplaces immeasurably more hazardous for workers, and also for customers. That’s because litigation — or the threat of litigation — is one of the bulwarks of workplace safety enforcement.

True populists wouldn’t be punishing workers by cutting their unemployment benefits.

Without confidence that workplaces are safe, employees will be reluctant to come to work and customers reluctant to walk in the door.

“Ensuring that workers and consumers can hold companies accountable for their actions is critical to establishing a safe reopening of our economy,” Celine McNicholas and Margaret Poydock of the labor-associated Economic Policy Institute have observed.

The proposal would supersede such federal worker safeguards as the Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970, the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 and the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act of 2008, among others.

In plain English, the Republicans are proposing to eviscerate almost all workplace protections at the moment when the threat to workers’ health may be at its highest in a century. Let’s not overlook that federal enforcement of workplace safety is anything but strong to begin with. The maximum OSHA penalty is $13,494 per violation.

That’s “insufficient to serve as a deterrent,” McNicholas and Poydock say. “Companies merely factor these penalties into the cost of doing business.”

In a surfeit of irony, or perhaps cynicism, the GOP titled its measure the “Safeguarding America’s Frontline Employees To Offer Work Opportunities Required to Kickstart the Economy Act,” or the “SAFE TO WORK Act.”

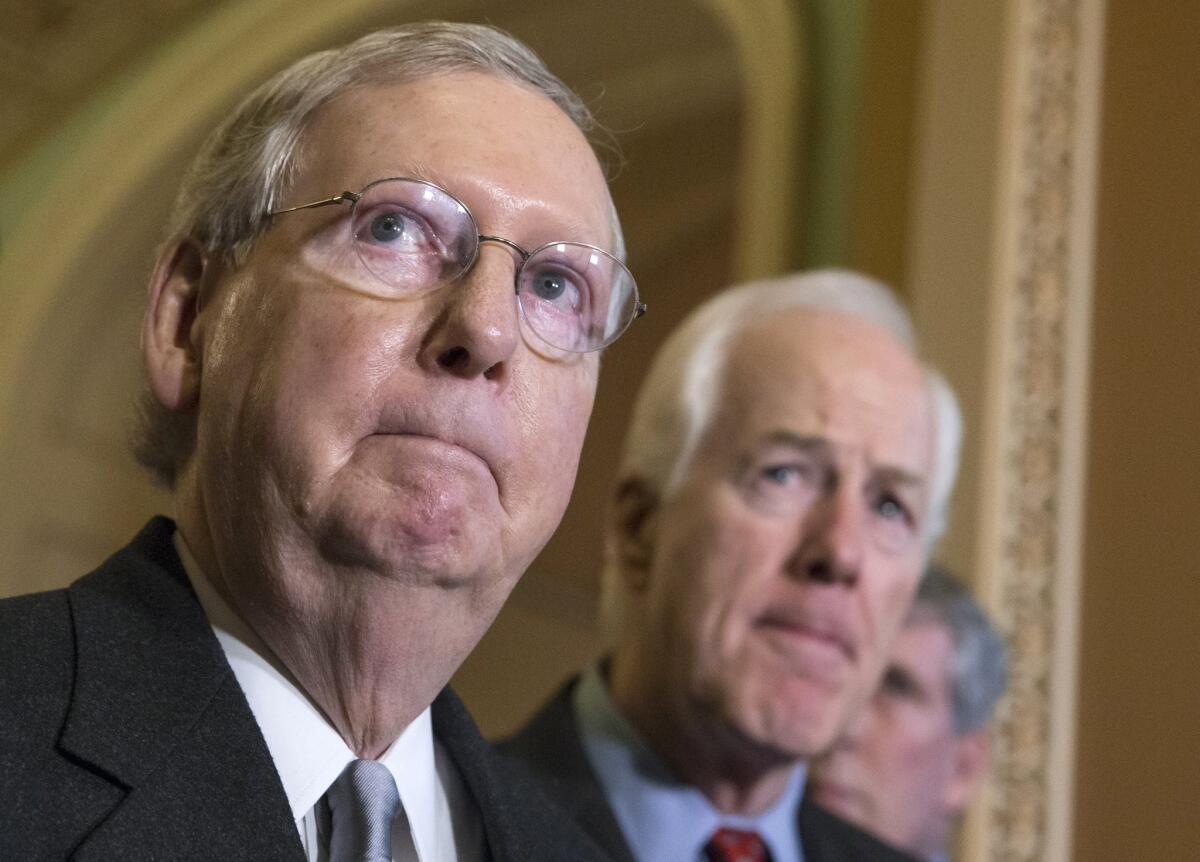

The measure, which was formally introduced by Sen. John Cornyn (R-Texas), states that it’s aimed at “discouraging insubstantial lawsuits relating to COVID-19.” It doesn’t define “insubstantial,” however.

Social Security advocates are universally opposed to the measure, which they see as an expression of longtime conservative hostility to the program.

The Republican proposal is more draconian than measures in some of the nine states that have given businesses immunity from lawsuits in the COVID-19 pandemic. It reflects a long-term conservative goal of absolving businesses from responsibility for conditions in their workplaces.

The campaign has been spearheaded by the Koch-backed American Legislative Exchange Council, which has been developing a model law on the subject for state legislatures.

Like the federal proposal, the state laws generally allow lawsuits only in cases of “gross negligence or willful misconduct” and require that plaintiffs show the defendant’s fault by “by clear and convincing evidence.”

That’s a higher bar than the typical requirement of “preponderance” of the evidence, which has sometimes been described as a balance in which one side’s case outweighs the other by even a smidgen.

Let’s take a look at the particulars.

The bill would move all liability cases to federal court, which instantly would increase the costs for plaintiffs. But it also imposes huge obstacles to even filing a claim.

In their initial pleadings, plaintiffs would have to list “all places and persons” they had visited and all persons who visited their home during the 14 days before they suffered symptoms of COVID-19.

Uber and Lyft are being squeezed by enforcement of California’s gig worker law.

They would have to explain specifically why they believed that none of those persons or places were the cause of their infection. They would have to submit “proof” of the employer’s “particular state of mind.”

What requirements would employers have to meet to be immune from a lawsuit or from any enforcement action by a federal, state or local regulator? Not many.

They’d have to show that they had been “exploring options” to comply with federal employment law, or had determined that the risk of harm to public health or the health of employees could not be “reduced or eliminated by reasonably modifying policies, practices, or procedures.”

In other words, an employer could exempt itself from federal labor law by examining its “options” or deciding that maintaining a safe workplace was just too darned hard to achieve. If a business issued or posted a written policy on limiting transmission of the coronavirus, that would be enough to achieve immunity from lawsuits.

“If a business printed out a [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] guideline and called it a policy, voila, they get a presumption they made reasonable effort,” observes Max Kennerly, a Philadelphia plaintiffs’ attorney who examined the GOP measure in detail and posted his concerns on Twitter.

But the measure also says that a lack of a written policy can’t be held against the business in court.

The measure incorporates another item on the GOP’s wish list of litigation obstacles: a limitation on damages. It says that plaintiffs can only collect for actual damages unless they can show “willful misconduct” by the employer, and that even in that case punitive damages can’t exceed actual damages.

Trump demands to cripple Social Security as his price for a COVID-19 rescue bill

This is a familiar stratagem aimed at making it uneconomic to bring so-called tort lawsuits. Plaintiffs’ lawyers typically work on contingency arrangements — they shoulder the costs of a lawsuit with the expectation that they’ll cover those costs, plus a profit, from a jury’s punitive award if they win.

Limiting punitive awards means that in many cases there won’t be enough money even to break even, much less earn a living. Ergo, tort lawyers will be loath to take COVID cases. For the GOP, this is mission accomplished.

The most obnoxious provision of the GOP proposal is one that shifts the liability in COVID cases from the employer to employee. This provision allows employers to sue employees or their representatives for bringing a claim for a COVID infection and offering to settle out of court.

Most specifically, the measure mentions “demand letters.” These are communications to a prospective defendant setting forth the facts of the claim, evidence assembled by the plaintiff, a reckoning of the potential damages and a statement of how much the plaintiff would accept to make the case go away. Here’s a sample letter published by the San Francisco law firm Rouda Feder Tietjen & McGuinn.

These documents are often designed as an opening brief in a negotiation; because neither side in an injury case really wants to go to trial, they make sense. The GOP bill would make anyone offering to settle, either through a demand letter or otherwise, liable to be sued for damages if the case they’re making is “meritless.” That’s another term that’s undefined in the measure.

Unlike the limitation on damages elsewhere in the bill, by the way, the punitive damages that can be awarded to employers bringing these lawsuits aren’t capped.

The measure also gives the attorney general the right to bring his own lawsuit in such cases. As a result, Kennerly observes, Atty. Gen. William Barr would get the right “to sue unions, labor activists, lawyers, doctors — everyone involved in coronavirus claims.”

So let’s not pretend that the Republicans have the welfare or health of working Americans at heart. They may talk about the virtues of work and the need to get workers back on the job for their own health and that of the economy.

The “SAFE AT WORK Act” proves with every line that they’re lying. Democrats on Capitol Hill should draw their own red line against it, and not budge an inch.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.