Column: Senate GOP votes to put U.S. back on gold standard, one of the worst ideas ever

While most of America was fixated Tuesday on the coronavirus pandemic and what the future might hold, Republicans on the Senate Banking Committee voted to move the country’s economic policy back to the 19th century.

The action came in the form of a party-line vote to advance the nomination of Judy Shelton as a member of the Federal Reserve Board to a floor vote by the full Senate. The defining feature of Shelton’s economic viewpoint, you see, is a return to the gold standard.

The foolishness of this position is hard to overstate. During its reign, which ended about 100 years ago, the gold standard fomented unemployment and obstructed governmental control of national economic affairs. It helped bring about and subsequently worsened the Great Depression.

Under a gold standard, money regains its primary purpose as a vital tool of free markets instead of serving as a corrupted instrument of government policy.

— Federal Reserve Board nominee Judy Shelton

On the far right, the gold standard era is cherished as a beacon of economic stability. Modern economic thought finds that to be the opposite of the truth.

“Far from being synonymous with stability,” UC Berkeley economist Barry Eichengreen wrote in his 1992 book “Golden Fetters,” “the gold standard itself was the principal threat to financial stability and economic prosperity between the wars.”

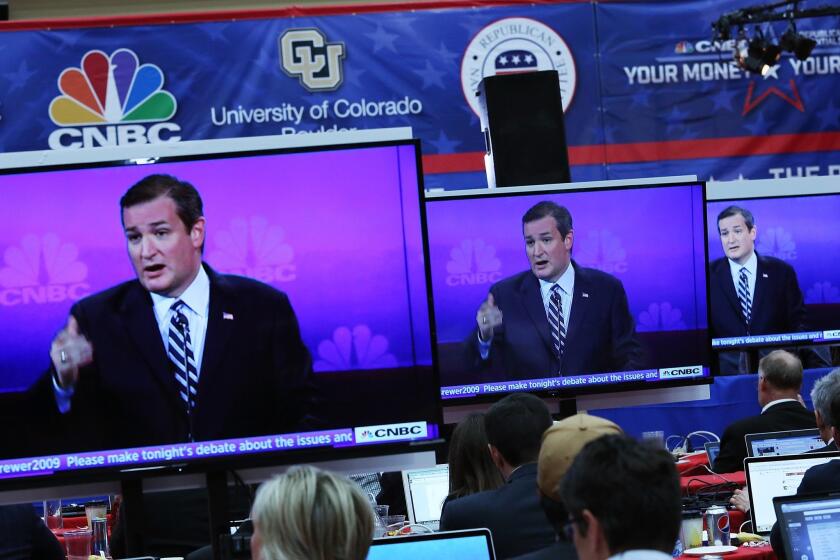

The last time the gold standard was put forth on the national political stage was in 2015, during the run-up to the 2016 presidential election. At that time the banner was waved in the name of “sound money,” as it was by then-candidate Sen. Ted Cruz (R-Texas) during a televised debate.

“We need sound money,” Cruz said. “I think the Fed should get out of the business of trying to juice our economy and simply be focused on sound money and monetary stability, ideally tied to gold.” Cruz’s position was at least tacitly endorsed by his then-rivals Sen. Rand Paul, Ben Carson, Mike Huckabee and Chris Christie.

Shelton has been planting the flag for the gold standard for years, tying it to the conservative mantra of smaller government.

The physicist Wolfgang Pauli had a concise retort to a theory or paper that was so fundamentally incorrect that it beggared analysis.

In a 2011 essay for the Weekly Standard, she wrote, “What gold brings to the monetary table is discipline .... A gold standard brakes runaway government spending. It allows individuals to defeat governments that dilute the value of money .... Under a gold standard, money regains its primary purpose as a vital tool of free markets instead of serving as a corrupted instrument of government policy.”

Since her name bubbled up last year as a possible Trump nominee for the seven-member Fed board, which sets monetary policy for the U.S., Shelton has conceded that a return to the classical gold standard in which currency could be freely converted to gold is probably not “feasible” today.

That’s not what she wrote in 2011, when she dismissed the notion that “the effort to reaffirm a gold link for the dollar is politically quixotic.”

To understand the possible ramifications of Shelton joining the Fed board, it will help to take a canter through gold standard history.

On the surface, the system is simple. The value of national currencies is pegged to an arbitrary value of gold, and through that pegged to one another.

In its purest form, at the end of the 19th century and the first decades of the 20th, currency could be converted to gold on demand. Balances of payment between countries were settled by the shipment of gold from one to the other.

Whether you call them visionaries or call them chuckleheads--or anything in between--you should tip your hat to the Texas legislature and Gov.

This system’s dominance as what Eichengreen calls “a remarkably efficient mechanism for organizing financial affairs” began roughly in 1870 and lasted until the outbreak of World War I in 1914.

That’s a clue to its unrecognized fragility — it worked until suddenly it didn’t anymore.

The downfall didn’t result merely from the fiscal pressures and political turmoil of the war, but from the growing recognition that the gold standard benefited one particular economic class — creditors, who desired the returns on their assets to be protected from inflation.

If the economy of one country ebbed relative to another, preserving the gold standard meant that someone else would have to sacrifice — typically laborers, who would be thrown out of work or subjected to wage cuts.

In the pre-Keynes era, the connection between the gold standard and unemployment was poorly understood. Joblessness was typically blamed on moral turpitude among the unemployed (a view that prevails to this day among many conservatives). In the U.S., observes Eichengreen, jobless individuals were customarily described as “out of work, idle, or loafing but rarely as unemployed.”

Nor was there any awareness that deficit spending, especially on public works, could be used to preserve employment and therefore address economic instability.

The classical gold standard was replaced after the war by a weaker jury-rigged system that Eichengreen argues bore the seeds of its own destruction. As the 1930s economic slump deepened into depression, country after country abandoned the gold standard. The U.S. was one of the last, largely because Herbert Hoover resisted the move.

In the words of Henry Morgenthau, Franklin Roosevelt’s second Treasury secretary, Hoover stuck to the gold standard even after it was abandoned by Britain and France, “evidently under the impression that that was a proud achievement, when it was obviously economic suicide.”

Nevertheless, FDR’s decision, shortly after his inauguration, to abandon the gold standard shocked members of his Cabinet. Walking the streets that evening with James Paul Warburg, a Wall Streeter and Roosevelt economic advisor, FDR’s conservative budget director Lewis Douglas muttered, “This is the end of Western civilization.”

After World War II, economic policymakers struggled to find a version of the gold standard that would work in the modern world. That ended in 1971, when Richard Nixon permanently ended the pegging of the dollar to gold.

Economic policy experts rolled their eyes at President Trump’s last reported nominee for the Federal Reserve Board, Stephen Moore, a right-wing ideologue with an almost unblemished record of getting his facts and economics wrong.

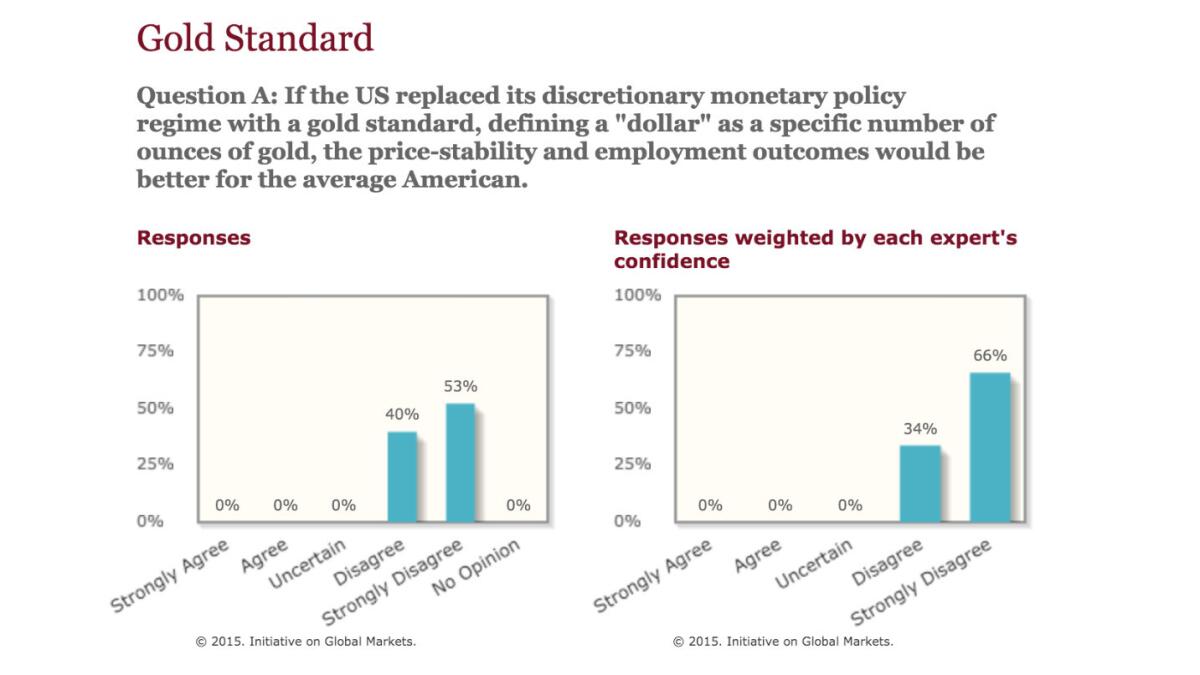

Since then, the gold standard has fallen even more deeply out of mainstream economic thought. When the University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business polled its panel of 51 experts, drawn from across the ideological spectrum, if any thought that a return to the gold standard would be “better for the average American,” not a single one thought so.

It doesn’t take much to understand who Shelton is speaking up for when she advocates the gold standard — it’s right there in her work. Her position would place new fetters on U.S. economic policy. The current state of affairs gives a hint of what the harvest would be.

There would be no coronavirus relief legislation, because it relies on deficit spending. So no unemployment support, no support for businesses, small or large. No support for states and cities hobbled by the pandemic. No support for research into vaccines or treatment.

The tax cuts for the wealthy enacted by Republicans in 2017 would presumably be all right, because Shelton’s focus is on bringing government spending in line with revenues, so if revenues decline, just cut the budget.

Republicans on the committee ignored these implications in voting to send Shelton’s nomination to the floor. “Many have tried to characterize Dr. Shelton’s views of the gold standard and monetary policy as outside of the mainstream thought and disqualifying for this position,” committee Chair Mike Crapo (R-Idaho) said after the vote. “I strongly disagree with these characterizations.”

He’s wrong. Make no mistake. The GOP majority on the banking committee has voted for a return to a discredited, and discreditable, past.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.