Coronavirus closures rock California restaurants, again

Homayoun Daryani was training servers and cooks for his soon-to-open gourmet hamburger grill in March when California abruptly shut down dine-in restaurants to slow the spread of the coronavirus.

After a three-month delay, Daryani held the grand opening for Slater’s 50/50 in Santa Clarita on June 18, after the state allowed restaurants to operate with limited capacity. It would be a brief reprieve.

Gov. Gavin Newsom on Wednesday shuttered indoor dining for at least three weeks across much of the nation’s most populated state, warning that infections were rapidly climbing.

The sudden reversal, less than two weeks after Daryani opened the doors of his restaurant, left him stunned and in a financial fix. He had stockpiled fresh beef and produce for a busy Fourth of July weekend, which could turn into a five-figure loss.

He’s struggling — again — to keep 60 workers on the payroll with nearly 300 seats inside his restaurant empty. He has a takeout window and room for 80 on his patios, where customers are allowed to eat because the threat of virus transmission is lower outdoors.

The latest order “is a huge step back for all the restaurants,” said Daryani, who also runs a catering business. “It’s not fair to anybody.”

As workplaces reopen amid the coronavirus pandemic, we want to hear from readers.

The coronavirus crisis has left millions unemployed, but few businesses have been hit as hard as California’s estimated 90,000 restaurants. Industry experts predict that as many as one-third of them will never reopen, while others are trying to navigate a maze of new sanitation rules and guidelines for physical distancing that have gutted seating charts and boosted in-house costs.

“It’s chaos,” said Jot Condie, president and chief executive of the California Restaurant Assn.

California had been successfully managing the virus; through May, Newsom moved quickly to reopen much of the economy. But troubling signs emerged in mid-June and have only worsened. Confirmed COVID-19 cases and hospitalizations have skyrocketed, and Newsom took action this week to try to reverse the trend.

The Democratic governor also shuttered bars, movie theaters, museums and other indoor venues in most of the state. Even singing in churches is forbidden.

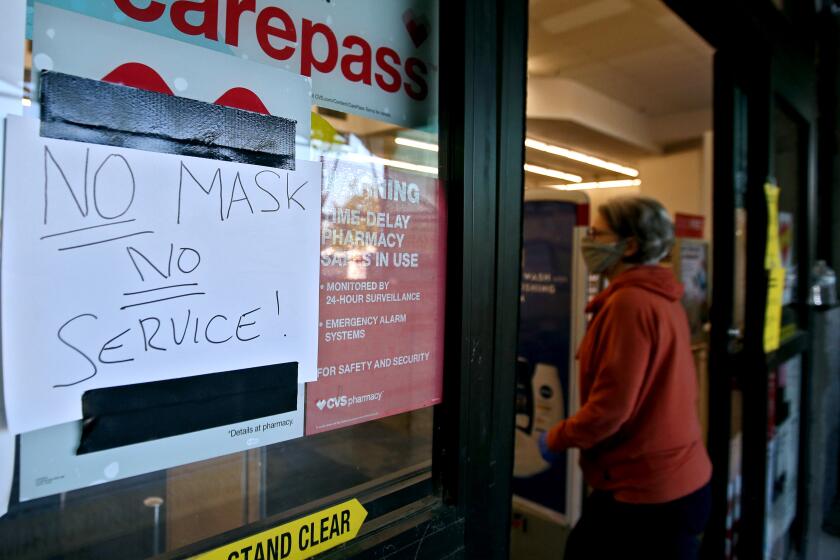

The latest order was especially painful for those in the restaurant industry who believed they had done everything right, investing in staff training and gloves, masks and other supplies to meet health restrictions.

At Guerrilla Tacos in Los Angeles, chef and owner Wes Avila had just reopened Wednesday after two weeks of employee training for pandemic-era food service. Now, like Daryani, he has to come up with a new plan.

“There’s not, like, a consultant you can hire to fix this,” Avila said.

When the outbreak began, Avila was forced to downsize from more than 50 employees to four and pivot to takeout and delivery. When he reopened as a sit-down restaurant, he brought back employees and even hired new ones, going up to 46.

Now, he’s worried he’ll have to halve his staff after Newsom blocked indoor dining in 19 counties.

Many owners believed they had been part of the solution when dining resumed last month, with limited seating, one-use paper menus and teams of mask-wearing employees routinely sanitizing tables, bathrooms and other surfaces.

Restaurants were required to establish a COVID-19 prevention plan, assess the risk at all work areas and designate a person to oversee safety procedures.

“We haven’t seen evidence that suggests these cases are from restaurants,” said Condie, referring to the surge in new infections.

That was echoed in the state Senate by Republican Leader Shannon Grove from Bakersfield, who lamented that many of the darkened restaurants are small businesses run by families.

There are “no data showing it’s restaurants” driving up virus cases, she said.

But health officials have tied outbreaks to restaurants, including 14 cases in San Diego County in the last week. In Los Angeles, with its internationally lauded food culture, health officials have visited thousands of restaurants to check for compliance with mask and social distancing rules. In many cases, inspectors found problems.

In Orange County, a succession of restaurants have temporarily closed after one or more employees were infected with COVID-19.

Even with capacity limited to 60%, business had been brisk for Daryani during his brief run with indoor dining.

He faulted the state for moving too quickly to reopen businesses, then ordering owners to reverse course with no warning. In a resigned voice, he acknowledged that “government has to do what it has to do.”

Can he make it financially with his indoor dining room closed?

“Definitely not,” Daryani said. But he intends to try. “What is the other option?”

Associated Press writers Stefanie Dazio, Adam Beam and Julie Watson contributed to this story.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.