Column: Citing coronavirus, Sutter seeks to renege on ‘historic’ antitrust deal

Here are a couple of points about the giant Sutter Health hospital chain that are indisputable.

First, the landmark settlement it reached in December with California Atty. Gen. Xavier Becerra would hit it in the pocketbook, hard because the deal included a $575-million financial penalty among other costly features.

Second, the coronavirus crisis has devastated Sutter’s bottom line — as it has those of many other hospitals and healthcare chains.

The plaintiffs are not going to renegotiate the settlement agreement.

— Deputy California Atty. Gen. Emilio Varanini

Sutter now is trying to exploit the second point to undermine the first one. It has asked the judge overseeing the settlement to defer final approval of the deal, hinting strongly that it wishes to rewrite key elements it already agreed to.

Becerra has replied, in effect: No dice. “The plaintiffs are not going to renegotiate the settlement agreement,” Deputy Atty. Gen. Emilio Varanini told San Francisco County Superior Court Judge Anne-Christine Massullo at a May 29 hearing.

That’s encouraging. The truth is that, although Sutter has unquestionably incurred a deep financial hit from the coronavirus — it says in an interim financial statement it lost nearly $1.1 billion in the first three months of this year on revenue of $3.2 billion, and an additional operating loss of $360 million during April.

That said, the chain is still sitting on pants-fulls of money; as of Dec. 30, it said in the financial statement, it had $6 billion in cash and liquid investments.

Sutter’s poor-mouthing provides an ideal opportunity to examine just how the coronavirus has affected the finances of our leading hospital firms.

When big hospitals merge, the merger partners’ mantra is almost always the same: The deal will deliver lower costs to the lucky patients, with no sacrifice in quality.

It also allows us to revisit the anticompetitive behavior Sutter allegedly engaged in, which Becerra suggested underlay that enormous cash hoard. Here’s our bottom line: Becerra shouldn’t budge on the terms of the settlement, and Judge Massullo should approve it as submitted.

Let’s start with the antitrust case.

Becerra’s 2018 lawsuit alleged that Sutter Health, which has 24 hospitals and 34 surgery centers in Northern California, had exploited its size for years to

extract “illegally inflated prices” from insurers, employers and patients. The lawsuit built on a case brought earlier by the United Food and Commercial Workers union.

Among the challenged practices, Becerra pinpointed an “all or none” rule that Sutter began imposing in its contracts with health plans in 2002. Under this rule, Sutter wouldn’t allow any of its hospitals to be excluded by health plans from their networks, or even relegated to lower tiers that allowed patients to choose them at higher co-pays.

This poses a dilemma for payers because many Sutter hospitals are “must-have” institutions for insurers or their clients, whether because they’re highly valued by patients because of their reputations, or are the only suitable hospitals within particular geographic regions.

The debate over hospital mergers traditionally has focused on whether allowing hospitals within a local community to merge drives up prices in that community.

But the restriction prevents insurers or employers from steering patients to lower-cost hospitals, either by placing high-cost institutions outside the network or charging higher co-pays.

Sutter said that insurers were free to exclude any of its hospitals from their networks on request. But insurers testified that Sutter placed such punitive conditions on exclusions that the insurers had no practical option. The lawsuits further alleged that the chain imposed arbitration and confidentiality conditions in its contracts that effectively kept its rate secret.

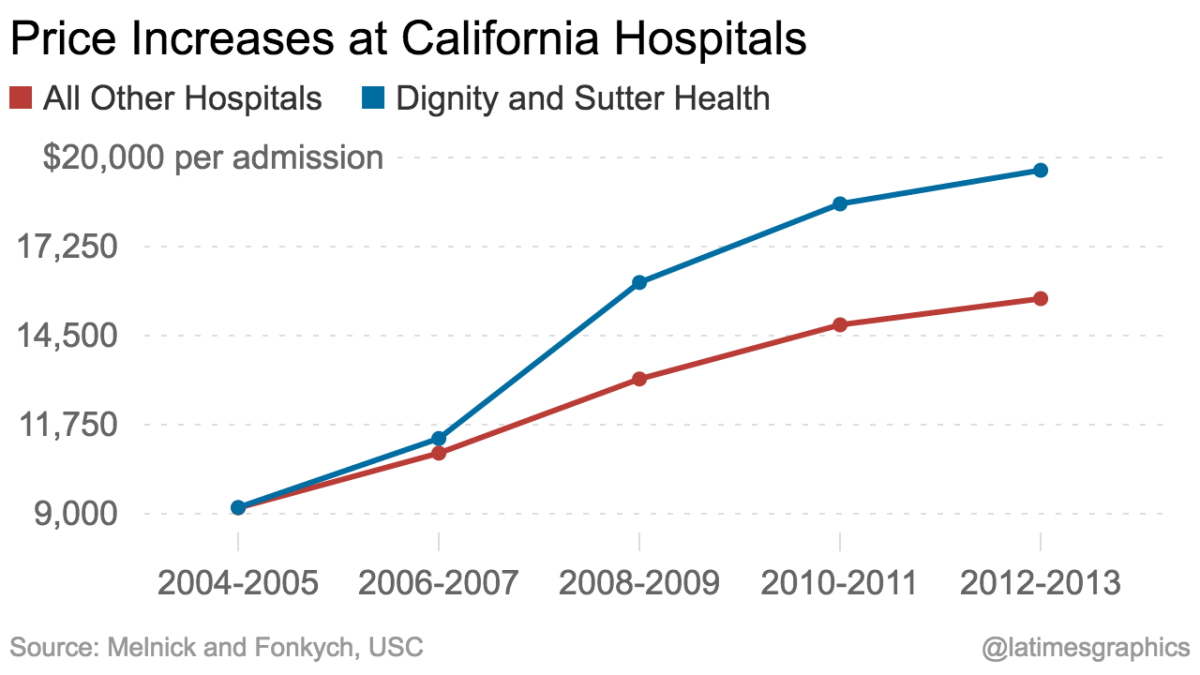

The whole set-up, Becerra alleged, amounted to an enormous price-fixing scheme that “injured the general economy of Northern California and thus of the state.” Inpatient prices in Sutter Health’s home ground were as much as 70% higher than in the far more competitive Southern California region, he said.

That conclusion was supported by academic research and a finding by the Federal Trade Commission. Sutter may not have been the only hospital provider in the region, but it set a mark that other providers shot for. “These guys set an umbrella price, and everyone else floats up,” Glenn Melnick, a healthcare expert at USC, told me after Becerra filed his lawsuit.

As costly as the settlement Becerra announced Dec. 20 appeared for Sutter Health, it was something of a win-win. Becerra rightly described it as “historic,” given the size of Sutter’s penalty and its agreement to cease the anticompetitive practices he alleged.

On the other hand, Sutter didn’t have to admit to any of those allegations. It avoided a trial, during which more details of its behavior might have been publicly aired and it capped liability that might have grown into the billions at a mere $575 million.

Yet come the pandemic era, Sutter has been expressing what we might call settler’s remorse.

The settlement agreement still requires Judge Massullo’s approval. The hospital firm has asked her to defer any hearing and final decision virtually indefinitely — as much as 30 days after Gov. Gavin Newsom declares an end to the pandemic emergency in California.

Sutter spokeswoman Amy Thoma Tan says that the chain “has not objected to any aspect of the settlement.” Rather, she told me by email, Sutter “asked to defer preliminary approval given the extreme disruption to the healthcare industry caused by COVID-19 and the potential for COVID-19 to materially impact certain settlement terms.”

Tan pointed me to the “incredibly costly and challenging endeavor” of adjusting its operations to the post-coronavirus reality “that will significantly impact us for years to come.”

California hospitals killed a measure aimed at protecting patients from surprise hospital bills

All that is true, as far as it goes. But it’s hardly the whole story.

Although Sutter hasn’t explicitly proposed scrapping any portions of the settlement, it said in a June 12 court filing that “the financial and operational effects of the pandemic could ... render impractical or otherwise materially impact” key features of the deal.

These include a cap on increases in out-of-network charges, which “may be too low to cover the unprecedented and unforeseeable increase in expenditures to respond to COVID-19.”

Sutter produced statistics showing that its outpatient surgical cases from March 17 to April 30 fell by 73%, compared with the six weeks before March 17. Emergency room visits were down by 43%, bed days by 23% and clinical visits by 60%.

Since these services make up much of Sutter’s financial bread and butter, the chain says it has been forced to close some facilities and cut back hours for some nonemergency services, resulting in reassignments or cuts in hours for more than 5,000 employees.

Becerra’s office doesn’t buy the argument that these conditions warrant revising the deal. In their brief explaining why Massullo should go ahead and approve the deal, Varanini and Richard Grossman, an attorney for the union, observed that although the COVID-19 crisis has changed the healthcare landscape, it hasn’t altered “the need for commercial insurers and Sutter to negotiate agreements” or alter “the underlying antitrust concerns” that motivated the lawsuits.

Concerns about religious restrictions on care helped to block a big hospital merger in California.

If long-term conditions eventually do show that some of the terms are too restrictive, that can be taken up under provisions that allow the settlement to be revised — later. In the meantime, any delay allows Sutter to continue the alleged behavior that drove up prices in the first place.

As for Sutter’s financial suffering, its claims deserve close scrutiny.

To start, there’s no guarantee that the reduction in healthcare demand cited by Sutter will be lasting. The company acknowledges that much of the reduction in business resulted from stay-at-home orders or health concerns that kept patients from visiting hospitals and clinics for elective surgery or nonemergency care.

The end of the crisis is may well bring about a resurgence of those visits. Sutter has had plenty of help navigating the crisis. It received more than $200 million in federal relief pandemic funds through mid-May, as well as a $1-billion prepayment of federal Medicare reimbursements to tide it over the pandemic hump.

The latter will have to be repaid, but the government has signaled that it will give hospitals up to a year to do so.

As for that $1.1-billion loss, about $500 million of it consisted of unrealized losses caused by the plunge in the investment markets earlier this year. But the markets have come back strongly since bottoming out in late March — the Standard & Poor’s 500 index has gained 40% since the slump, and as of Tuesday is showing a loss for the year of less than 4%.

Under the circumstances, Sutter Health has no business including its investment losses in its overall financial claims.

Judge Massullo has set July 9 for a hearing on Sutter’s request to defer approval of the settlement. She might choose to do so because holding any further hearings on the settlement itself might be complicated by the continuing emergency.

But one would hope that she would weigh carefully Sutter’s argument that the world has changed so drastically and permanently that portions of the deal might need to be scrapped — or whether it’s using the crisis as a pretext to renege on the deal it signed a mere six months ago.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.