Column: Republicans seek to exploit COVID-19 crisis to cut Social Security benefits

One has to hold begrudging admiration for the determination of the enemies of Social Security among Republicans and conservatives:

Not only are they refusing to let a global crisis such as the COVID-19 pandemic divert them from the long-term campaign to undermine the program, they’re using the crisis to justify cutting benefits.

The latest idea making the rounds of the anti-Social Security caucus is to pay for coronavirus stimulus aid for the neediest Americans by forcing them to borrow from their future retirement benefits to keep themselves fed and housed today.

Social Security is an earned insurance benefit. It is not a piggy bank.

— Alex Lawson, executive director of the advocacy group Social Security Works

Word that the White House is eyeing the idea comes from the Washington Post, which reported over the weekend that the administration is fretting about the impact on the national debt of the battle against COVID-19.

It’s no secret that Republicans have begun to muster a deficit argument against further assistance to Americans who have lost working hours or jobs because of the virus.

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) called for the brakes to be applied to further stimulus measures because of concerns about the federal budget almost immediately after passage of the $2-trillion CARES Act in April. Since then, they’ve solidified their stand against further relief.

What’s interesting, in a scary sort of way, is the option that Trump administration officials are pondering to keep further stimulus assistance from burdening the wealthiest taxpayers. The Post reports that they’re “exploring” a proposal put forth by two conservatives allowing workers to receive up to $10,000 today, but paying the money back by deferring their Social Security benefits once they retire.

The proposal comes from Andrew Biggs of the American Enterprise Institute and Joshua Rauh of the Hoover Institute at Stanford University. Biggs and Rauh sugarcoat their plan by calculating that a $5,000 loan would require a maximum deferral of just under five months, for a worker with very low income taking the loan at age 60.

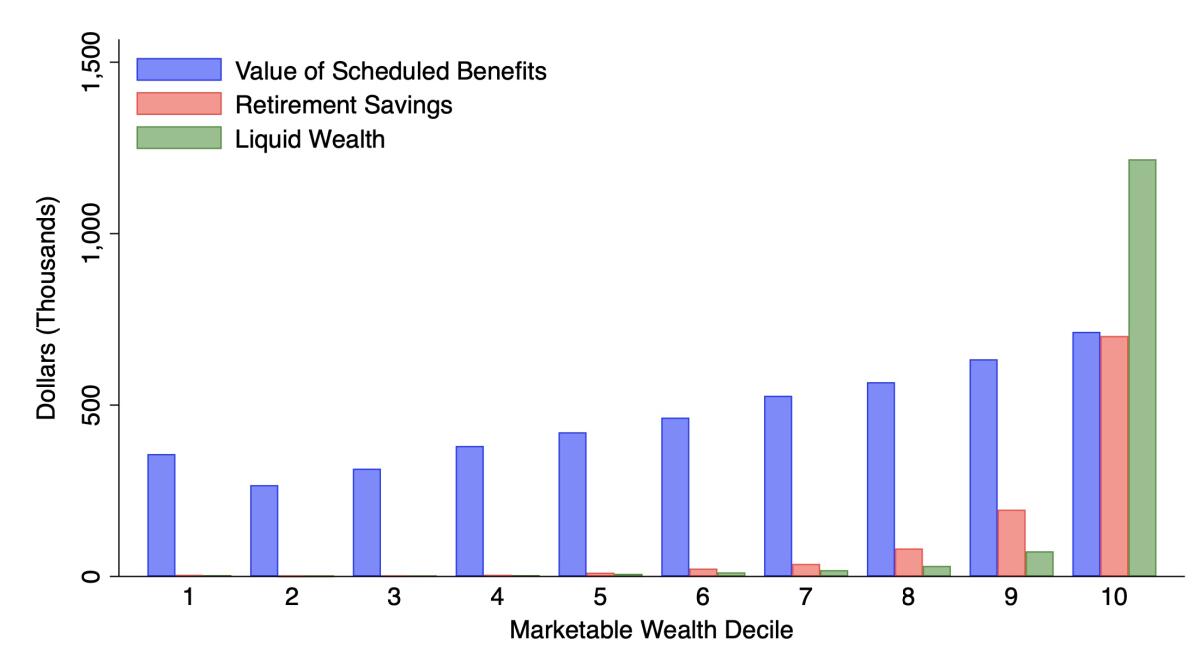

For higher-income and younger workers, the deferral would be shorter. But as Biggs and Rauh show, the burden is greater on those with the lowest incomes.

A worker earning the maximum Social Security covered wage ($137,700 this year) who takes out the $5,000 loan at age 25 would have to defer benefits upon retirement for less than a month. That worker would receive a partial benefit check in that first month and full benefits thereafter.

The Biggs and Rauh plan would charge interest every year from when the money is borrowed until retirement. They suggest 1.6% a year, which means that a worker who borrows at age 25 would end up owing about $9,700, or almost twice the borrowed amount, at retirement.

That said, it’s also true that scheduled benefits would also rise over one’s working life — if they rose by more than 1.6% a year on average, the relative cost of the repayment would shrink.

How seriously the Trump administration is considering this sort of plan is open to conjecture. Biggs told me by email that he’d had contact with White House staff over the idea, but solely on technical issues such as “how changes to the size of the loan or interest rate might affect the months of delayed benefits at retirement.”

He said he hasn’t had “any big-picture discussions that would tell me how seriously the policy is being considered.”

Any such proposal would likely run into a buzz saw from Democrats, who have been moving generally toward plans to enhance, not reduce, Social Security benefits. In part that’s because they recognize that the program is the most important bulwark against poverty in old age, especially for working-class Americans with limited access to retirement savings or pensions.

At their core, the proposals to use Social Security to fund stimulus benefits would effectively relieve the wealthiest Americans from their responsibility to society at large while hobbling the 99% with more of the burden. In the current case, they would force middle- and lower-income workers to bear the cost of the fight against COVID-19.

Social Security advocates are quite properly up in arms over the very concept.

“These ideas represent a gross misuse of Social Security for purposes unrelated to its core purpose: providing baseline retirement security for American workers,” asserts the National Committee to Preserve Social Security and Medicare.

They’re right. Proposals to prepay Social Security benefits misconstrue how the program is designed. As Alex Lawson, executive director of the advocacy group Social Security Works observes: “Social Security is an earned insurance benefit. It is not a piggy bank.”

That’s because Social Security is not solely a retirement plan. It’s a social insurance program combining disability coverage and survivor benefits with a pension, including inflation protection and lifetime benefits.

Over the decades, Social Security’s critics have had to confront this fact as an obstacle to myriad proposals to “reform” the program.

Defining Social Security as though it were merely an individual retirement account was a key to the effort under George W. Bush to privatize Social Security. (Biggs was a staff member of Bush’s privatization task force, and later an official of the Social Security Administration.)

Proposals to raid Social Security to provide lump sums for individuals have picked up steam in recent years. Sen. Marco Rubio (R-Fla.), joined forces with Ivanka Trump in 2018 to put forth a family leave benefit that would also be funded by parents giving up some of their Social Security benefits. They based their proposal on a plan that earlier had been floated by Biggs and libertarian lawyer Kristin Shapiro.

Before the economy recovers, GOP wants to stop giving aid

Earlier this month, a group of scholars at the Wharton School of Business attempted to give academic credibility to raiding Social Security, asserting that “giving workers early access to just 1% of their future Social Security benefits” would allow “most households to maintain their current consumption for at least two months.”

All these ideas seem superficially reasonable, chiefly because their arithmetic seems to work. What could be simpler than taking money now and paying it back 40 or 50 years from now? But as a matter of policy — especially Social Security and safety net policy — they make no sense.

Their effect would be to undermine Social Security by eroding its fundamental structure. The Wharton team put their finger on this directly.

“The lump-sum payment of Social Security benefits will hasten the depletion of the Social Security trust fund by a few years,” they wrote. “Thus policymakers will be forced to weigh entitlement reform, like increases in taxes or cuts for beneficiaries, sooner.”

One can already imagine the argument coming from the Republican caucus: “We would have preferred to preserve Social Security, but the virus forced us to cut it.”

The downside of “American exceptionalism,” that beloved mantra of “freedom-loving” conservatives and libertarians, is that it tends to leave Americans on the lower end of the income scale bearing the burden of exceptions.

The truth is that proposals to raid Social Security to pay for coronavirus relief would hit the most vulnerable Americans the hardest — they’re the people who are most desperately in need of money now, and would pay the relatively highest cost to get it. As the Wharton paper observes, “access to Social Security serves the needs of workers made vulnerable by the crisis, but does not increase the overall liabilities of the federal government.”

Since the overall liabilities of the federal government are conventionally covered most by progressive taxation — that is, the principle of heavier taxes on the wealthy — we can see who benefits the most from making Social Security pay the freight.

As Richard Johnson of the Urban Institute told me at the time of the Rubio/Trump family leave proposal, lump-sum Social Security payouts would add another drain to a retirement system that already leaves millions of Americans vulnerable.

“Already we have a retirement system that leaks a lot,” he said. “People can dip into their 401(k) savings or borrow against them, so people don’t get to retirement with as much savings as they should. The one thing they have now is Social Security, but if we let people borrow against Social Security, that adds to the precariousness of the retirement system.”

Another subtle subtext of these proposals is that many recipients of the latest stimulus checks— up to $1,200 per adult in households earning up to $150,000 — are undeserving. Checks will go not only to workers who have lost their jobs, but retirees whose income is unaffected by coronavirus lockdowns or government workers and others who haven’t been laid off or suffered cutbacks in hours.

Turning stimulus assistance into a voluntary program with costs down the road in Social Security benefits would limit the government outflow and help ensure that it goes to those who need it, Biggs and Rauh argue.

But those goals could be achieved while leaving Social Security out of the process. Unnecessary payments could be recovered by taxing them, for example. Next year’s 1040 tax form could ask: Did you suffer a layoff in 2020? Lose income? If not, add $1,200 to your tax bill.

Fundamentally, the question raised by these proposals is why Social Security has to be part of a stimulus program at all. Biggs and Rauh say it’s to avoid deficit financing, in which case “future taxpayers will have to pay off the debts incurred by the federal government, either through direct taxation or inflation.”

A reasonable response to that concern is: So what? Until the coronavirus crisis struck, the biggest contributor to the federal deficit over the next decade was expected to be the tax cuts enacted by Republicans in 2017, which would add more than $1.5 trillion to the decade’s red ink.

Those cuts went primarily to corporations and the wealthy. But the recipients weren’t asked to give up their Social Security benefits, or really to sacrifice anything, in return for the government’s largesse. Corporations weren’t even held to rules requiring that they invest their gains in wages or equipment, so many cranked the money out to shareholders by the billions via stock buybacks and dividends.

And now, incredibly, Republicans are crying poverty on behalf of a federal government that they systematically impoverished. As happens almost invariably, they’re planning to take the costs out of the hides of the neediest.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.