Column: California might behave as a ‘nation-state.’ But its power has limits

With its nearly $1-billion deal to acquire 200 million respiratory and surgical masks a month, amid a nationwide shortage of the crucial protective gear for first-line healthcare workers, California has demonstrated what seems to be a unique capability to chart its own course in the coronavirus battle.

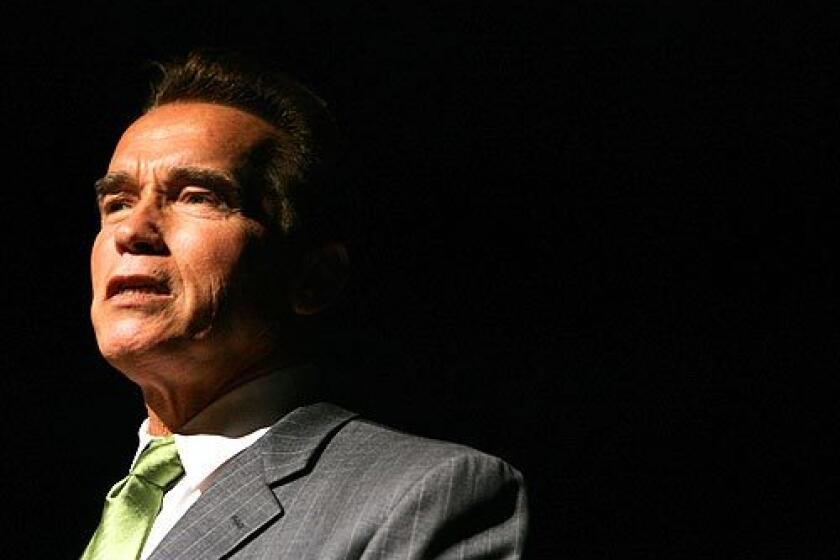

“We decided, enough’s enough,” Gov. Gavin Newsom told MSNBC host Rachel Maddow on Tuesday in announcing the deal, which has inspired admiration for its audacity as well as questions among lawmakers in Sacramento about transparency. “Let’s use the purchasing power of the state of California as a nation-state.”

Newsom’s description of California as a “nation-state” was instructive, for it underscored the advantage of the state’s size while hinting at its limitations.

One cannot be Pollyannish and understate the magnitude of impact to state coffers but also to local governments that were already stretched a few months ago.

— California Gov. Gavin Newsom

It’s true that California’s economy is world-class in its sheer magnitude — its 2019 gross domestic product of $3.14 trillion would rank fifth in the world, ahead of Britain and France, were it an independent country. But because it’s a state, California faces constraints on its ability to manage its own affairs that could turn into brick walls as the coronavirus crisis unfolds.

The state’s healthcare policies, such as its wholehearted embrace of the Affordable Care Act, have given it tools to manage the immediate public health ramifications of the crisis better than many others.

Its proactive implementation of stay-at-home orders and other social distancing measures may have resulted in lower infection and death rates from COVID-19, the disease caused by the virus, than in states such as New York, where infections surfaced about the same time but action came later.

But there is only so much that a single state can do without assistance or cooperation from the federal government. The limitations are legal, administrative and financial. While California’s fiscal resources are great, they’re not unlimited.

California’s full-on acceptance of the Affordable Care Act has yielded dividends for the state, its residents and even the federal government.

While the federal government can essentially print money to finance its programs, California must enact a balanced budget every year. And that requirement is almost certain to bite harder as tax revenues sink as a result of business shutdowns, soaring unemployment and the stock market slump.

“One cannot be Pollyannish and understate the magnitude of impact to state coffers but also to local governments that were already stretched a few months ago,” Newsom told me. “It’s not only the front-end revenue loss; it’s the back end in increased responsibility to deepen and broaden the social safety net ... for those who have been most impacted, which is low-income [households].”

He said he has written to House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-San Francisco) to emphasize the need for more stimulus help for states and localities from the federal treasury.

Newsom has the support of state trade leaders in that appeal. “State and local government is not going to have a dime left,” says Robbie Hunter, president of the State Building and Construction Trades Council. “They’re going to shut down public works construction, and we’re going to have 2008 on steroids.”

Newsom has avoided banning major construction projects, as some other states have done, in order to keep construction workers on the job and public works projects on track.

Pain from changes in the fiscal landscape will be especially acute in California because Newsom and the Legislature had laid out an ambitious expansion of help for low-income Californians, including broader eligibility for Medi-Cal, the state’s Medicaid program, regardless of applicants’ immigration status.

Without minimizing the scale of the economic plunge, it’s proper to place comparisons between today’s figures and economic situation and those of the Depression in perspective. In short: The differences are greater than the similarities.

The state also expanded premium subsidies for enrollees in Affordable Care Act health plans through Covered California, its individual insurance exchange.

These expansions reflected the assumptions as recently as January that the state budget was flush, its economy on a roll and its budgetary rainy-day fund on pace to reach $21 billion by this summer.

All those expectations have had to be revised. The crisis could exhaust the budget surplus within months. The economic reversal, moreover, has underscored the structural flaws of a state tax system that minimizes property tax revenue (thanks to Proposition 13), leaving it dependent on income tax, especially from the wealthy.

“The reality is that we’re in a state that’s overly reliant on capital gains,” Newsom says. As a result, the volatility of tax receipts “will be acute.”

California is relatively well prepared to manage the public health ramifications of the coronavirus crisis.

“California is in a better place than other states because we were aggressive in implementing and improving on the Affordable Care Act,” says Anthony Wright, executive director of the nonprofit advocacy group Health Access California. “We have the Medicaid expansion, we have set up our own exchange, we did things just in the year to expand Medi-Cal.”

President Trump lies again about the reasons for the Postal Service deficit

Still, the state can’t achieve everything it wishes without the cooperation of the federal government, especially when it comes to Med-Cal, since as a version of Medicaid it’s a joint state-federal program.

The state has applied for several waivers of Medicaid rules, which are permitted by law with government approval. Most are still pending, but the state recently won approval of one change that had become a bone of contention with the government.

That was a request for a tax on managed care organizations that was expected to provide $1.5 billion for Medi-Cal starting next year.

The federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services rejected the application last year, raising concerns that the agency was acting on President Trump’s oft-expressed disdain for California policies rather than on the merits. On April 3, however, the agency signed off on a revised request through fiscal 2022-23.

“That was a big, big boost for us,” Newsom says. “I don’t think that would have happened were we not in the throes of this crisis. We were ready for litigation.” In the heat of the crisis, he says, the relationship between the state and the Trump administration “has improved substantially in the last few weeks,” at least on healthcare, as the approval demonstrates.

A public health expert shares how to crush the virus. But we’re way behind.

California faces other challenges as one state among many rather than a sovereign. It has almost no ability to control its own borders, for example. That could pose a risk should the state’s success in suppressing and mitigating COVID-19 infections not be matched in states that haven’t acted to encourage social distancing as proactively.

“In California, given the responses in other states, one thing that’s going to be an issue is whether you restrict people coming in from Utah, or Texas, or Florida or any other state that has a later spark in the virus,” says Kevin Klowden, an expert on regional and California economics at the Milken Institute. Some states, including Florida, have dictated that travelers from “hot spot” states must self-quarantine for weeks after they cross the state line.

“California is a large state with a lot of different entry points,” Klowden observes. “This is why you’ve got huge concerns in terms of the federal government relationship, because you have to be able to coordinate travel issues and make sure that if 70% of the country gets the virus under control but 30% doesn’t, it doesn’t come back.”

Not all the pressure on California policy will come from outside the state. Battered by stay-at-home orders, the California Restaurant Assn., for instance, has already asked Newsom to defer scheduled increases in the state minimum wage, aimed at raising it from the current $13 per hour ($12 for employers of 25 workers or fewer) to $15 by 2022 or 2023.

“When the COVID-19 crisis passes, there will be scorched earth on the restaurant and employment landscape,” the association said in a March 27 letter.

The proposal is sure to be opposed by labor representatives. “We’re going to be playing defense against a lot of corporate lobbying issues,” Steve Smith, a spokesman for the California Labor Federation, told me.

The real challenge for California will come when it tries to start reopening its economy. The phase depends on vastly expanding its testing capability for signs of coronavirus infection in the general population. Shortages of testing supplies, including swabs and chemical reagents for the tests, loom as obstacles to the process.

“We just have to scale that exponentially,” Newsom says. “That remains an issue, especially if we talk about the next iteration, which is getting back to work: How do we go back to some semblance of normalcy?”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.