Column: A newspaper company’s bankruptcy stirs fears about the death of local news

Executives of McClatchy Co. — the owner of the Sacramento Bee, Fresno Bee, Miami Herald and 27 other daily newspapers across the country — put a brave face Thursday on their decision to file for bankruptcy protection.

The filing under Chapter 11 of the Bankruptcy Code would enable the company to manage its more than $700 million of debt, brightening its prospects, they said. In a few months, after a reorganization, “we expect to be even better positioned to ... continue delivering essential local news to our subscribers and readers in the communities we serve.”

Yet the story of McClatchy lends itself to a darker spin. The company is likely to emerge from bankruptcy under the control of its largest creditor, the hedge fund Chatham Asset Management.

If we keep looking at newspapers as products owned by shareholders who want a return year over year, it’s not going to work.

— Nick Charles, Save Journalism Project

That would be a sharp turn in the company’s fortunes. Long considered a bastion of exemplary local journalism, McClatchy would be in the hands of a hedge fund known for its ownership of the National Enquirer during that tabloid’s recent scandals related to its relationship with President Trump and his fixer Michael Cohen. Chatham acquired a controlling interest in the Enquirer’s parent company, American Media, in 2014. Last year, Chatham forced American Media to put the tabloid up for sale.

Despite Chatham’s pledge, in a statement Thursday, that it’s “committed to preserving independent journalism and newsroom jobs,” McClatchy’s filing comes against the backdrop of fewer journalism jobs, the disappearance of local coverage and greater proliferation of misinformation in public discourse.

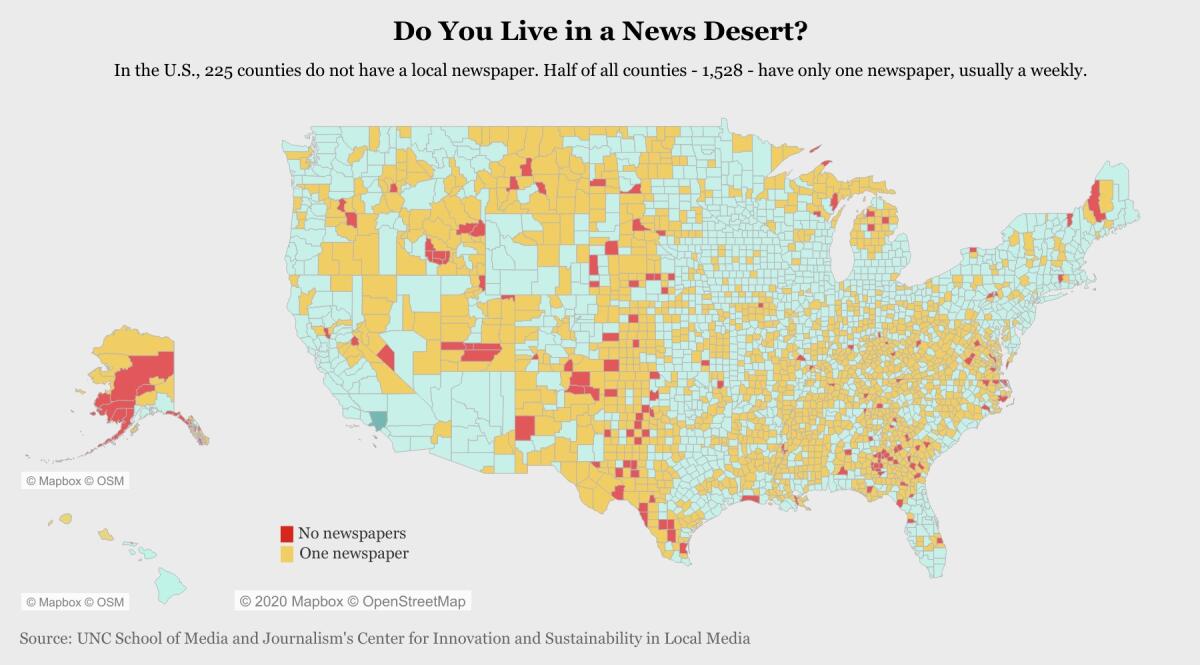

In short, the spread of “news deserts.”

Newspaper companies large and small have been struggling to come to terms with a transformation of their business that began before the turn of the century and has really taken hold since about 2006 — the year McClatchy took over a bigger competitor, Knight Ridder, in a $4.5-billion deal.

As newspaper readership has declined, a consequence of the aging of the newspaper-buying public and a shift to digital distribution of news, newspapers turned to cost-cutting. There were fewer reporters to cover local town boards, fewer features, fewer investigations, fewer compelling reasons for subscribers to renew.

A vicious circle took hold — fewer print subscribers and less advertising revenue begat more cutbacks, which drove away more readers and advertisers, which begat more cutbacks.

Among those who believe that the press provides value for society — especially local journalism that slaps state and municipal politicians’ hands out of the public cookie jar — Alden Global Capital is a “vulture investing” firm that makes real vultures look good by comparison.

“The business model for local news has collapsed,” PEN America reported in November. Not only have readers turned to digital news sources, if they seek out news at all, but the digital giants Google and Facebook have vacuumed up advertising that used to go to local newspapers and might yet go to the newspapers websites.

Those two companies accounted for more than 70% of all local digital advertising in 2018, according to the digital marketing firm Borrell Associates.

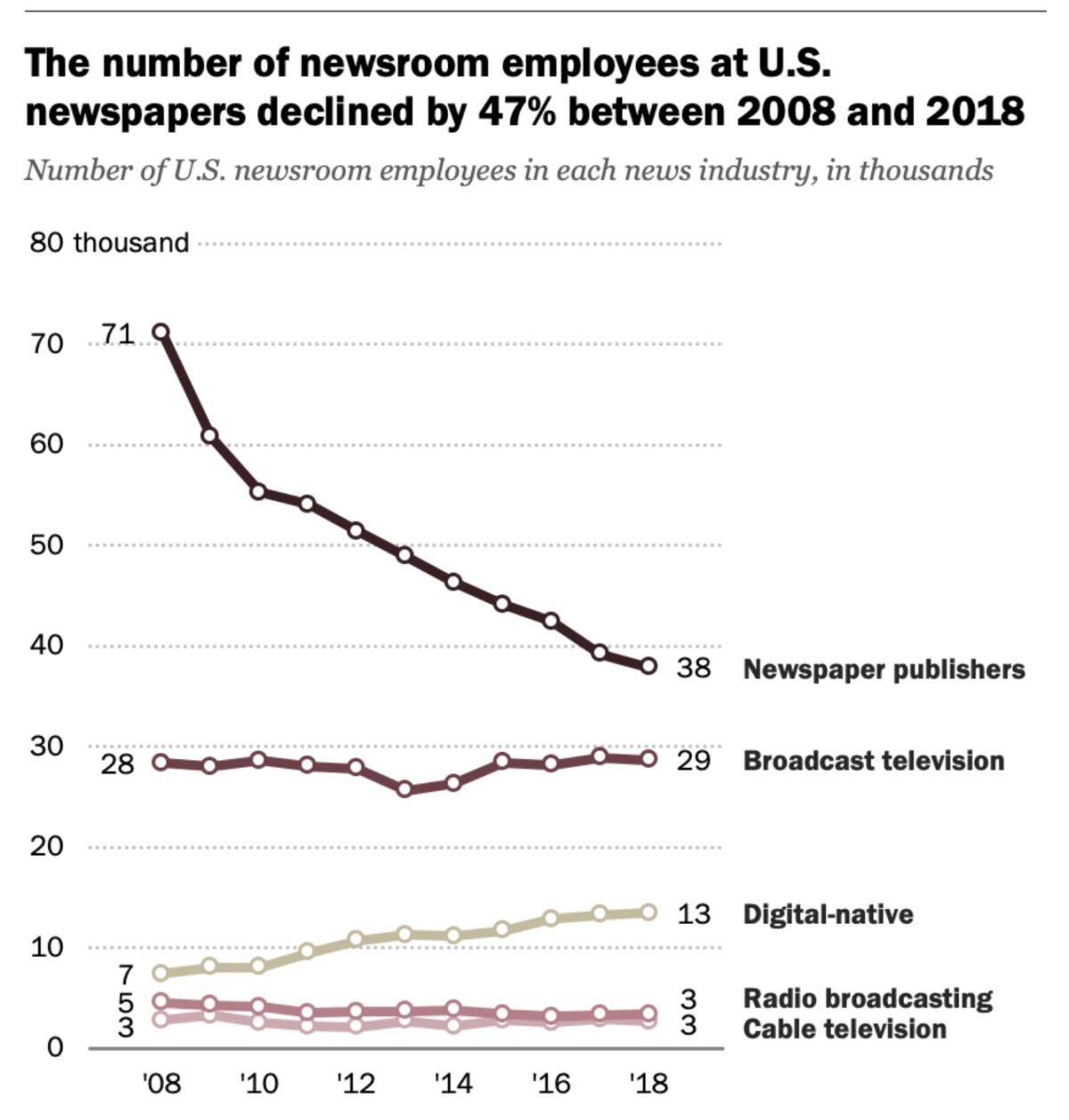

Journalistically speaking, the ball has rolled downhill. The Pew Research Center reported last year that 47% of newspaper jobs disappeared from 2008 through 2018, with employment falling to 38,000 from 71,000. Employment at digital news sites rose in that period to 13,000 from 7,000, not nearly enough to replace the army of reporters and editors leaving the business.

Unable to sustain themselves even with draconian cost-cutting, dailies and weeklies have disappeared from the American news landscape by the hundreds. Nearly 1,800 local newspapers went out of business or “morphed into shoppers or specialty publications” from 2004 to 2018, according to research by Penelope Muse Abernathy of the University of North Carolina, leaving fewer than 7,100.

Fewer objective eyes on local politicians and business entities often means scandals or wasteful policies going unexposed. But just as important may be the loss of community identity and cohesion that comes from a dearth of day-to-day reporting.

McClatchy says its “30 local newsrooms are operating as usual.” That should offer some relief in markets such as California, where the company owns the Sacramento, Fresno and Modesto Bee dailies as well as the Merced Sun-Star and the Tribune in San Luis Obisbo; North Carolina, where it owns the Charlotte Observer and two other newspapers; South Carolina, where it owns five including the State in the capital, Columbia; and Missouri, where it owns the Kansas City Star.

Gannett and GateHouse will merge into the largest U.S. newspaper company, but its future looks anything but certain.

But McClatchy has participated in the industrywide downsizing. In August 2018 it cut staff by about 100; in February 2019 it offered buyouts to 450 employees of whom 200 took the offers; and in October it announced layoffs of about 30 employees, or 1% of its 3,000-strong workforce.

“More insidious than big scandals is the absence of everyday reporting of the communities — the city council, what’s going on with zoning, what’s going on with the board of education,” says Nick Charles, a spokesman for the Save Journalism Project, a freelancer who worked at three newspapers that were later downsized--Newsday, the New York Daily News and the Cleveland Plain Dealer. “These are the routine things that we get from newspapers that are local outlets.”

News deserts tend to be communities that rank low in social stability and high in poverty, a study by the Columbia Journalism Review found. In general they have median household income 13% below the national average of nearly $63,000 and a poverty rate 4.7 percentage points higher than the national average of 12.3%.

They’re places like Colfax County, New Mexico, a former coal mining town that lost its local paper, the Raton Range, in 2013. The county’s poverty rate is nearly 20% and its median household income a mere $33,000.

But even large, thriving communities can lose their news coverage. Take Denver, which had two daily newpapers until 2009, when the Rocky Mountain News ceased publication. The remaining daily, the Denver Post, ended up in the hands of the private equity firm Alden Global Capital, which has made its name as a pitiless downsizer of news staffs at newspapers, including the Orange County Register and San Jose Mercury News.

Alden’s layoffs at the Denver Post were so ruthless that the staff staged protest rallies in 2018 at its Denver offices and New York headquarters. There’s no evidence that the protests changed Alden’s strategy of squeezing its newspapers for the last drops of profit on their way to oblivion. Alden has since become the largest shareholder of Tribune Publishing, owner of the Chicago Tribune and former owner of The Times.

As locally owned newspapers disappear, the vacuum has been filled in some locations by entities with less concern for objective coverage of their communities. That includes Richmond, Calif., the location of a major refinery owned by Chevron Corp.

Chevron is the force behind the Richmond Standard, a news website that prominently displays a feature labeled “Richmond Refinery Speaks,” an outlet for “Chevron Product Company’s views on issues important to the company and the Richmond, CA community.” The only other source for local journalism is Richmond Confidential, an online site staffed by students at the graduate journalism school at nearby UC Berkeley, which does excellent reporting but is captive to the academic calendar of the university.

The vacuum is also filled by neighborhood news sites such as Nextdoor, which allow residents to communicate with one another over concerns relevant sometimes to their own block. But that’s so hyperlocal that it can’t meet the demands of community coverage, nor does it offer a system to verify information being passed around by neighbors.

Facing a severe financial crunch back in 2013 and 2014, the then-owners of the Orange County Register cooked up a creepy plan to dig out of their hole: They bought life insurance policies on their own employees.

Ideas for reversing the disappearance of local news are few, in part because the financial travails of newspaper companies are too varied to be amenable to a single solution. McClatchy’s problems, for instance, stem not only from its debt load but its unfunded pension obligations, which were estimated at more than $528 million as of September.

The company said then that it wouldn’t have the cash or cash flow to make a required minimum contribution of $124 million to its pension fund this year and was negotiating a possible takeover of the plan by the government’s Pension Benefit Guaranty Corp. It’s still negotiating that takeover.

McClatchy tried to join in a partial bailout of newspaper pensions in the Secure Act, a retirement reform law Congress passed in December. The act allows some newspapers to gradually write off their pension obligations over 30 years rather than the customary seven, which would reduce their annual pension expenses. But it failed to qualify for the provision, which was aimed at one-state companies, in part because it was a large multistate enterprise.

McClatchy says its goal in bankruptcy is to eliminate about 60% of its debt.

Somehow, the news industry needs to restructure itself so that revenues accrue to the organizations investing in coverage. That means recovering a fair share of advertising dollars from companies such as Google and Facebook, which attract advertising in part by becoming the place where people find and discuss news stories.

But newspapers have questionable leverage over the tech companies, in part because they crave the access to audience that they gain from being posted on those websites.

One proposed solution for the decline of newspapers involves inoculating them in some way from the demands for quarterly or annual profits exercised by public shareholders or private equity firms with short-term horizons.

“If we keep looking at newspapers as products owned by shareholders who want a return year over year, it’s not going to work,” Charles told me.

That could mean turning over newspapers to nonprofit organizations as has happened with the Philadelphia Inquirer, owned by the Lenfest Institute for Journalism, which was established by its last private owner, and the Tampa Bay Times, owned by the Poynter Institute.

But nonprofit ownership isn’t a panacea. Lenfest faces legal constraints on its support for the Inquirer as long as the newspaper loses money, and the Tampa Bay Times has suffered from some of the same financial challenges as newspapers owned by profit-seeking entities — in October, hurting from the loss of a major advertiser and by a shortfall in digital revenues, it laid off seven employees and said it would hold off filling two vacancies.

The other common response to the loss of advertising support is to resort to a digital subscription model. In the move to online publication, news organizations gave readers full digital access for free — letting subscriptions fall by the wayside.

But now they’re taking digital subscriptions more seriously, placing most of their articles behind paywalls that require readers to pay for access.

This is the approach now taken by newspapers with a national footprint or in large metropolitan areas, such as the New York Times, Washington Post and Los Angeles Times, and those with specialized readerships such as the Wall Street Journal.

Whether that approach, coupled with pension relief and private ownership, can keep a place like Merced or Fresno from turning into a news desert is an open question.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.