How Kobe Bryant changed the sneaker world

Michael Jordan was professional basketball’s first signature shoe king, but Kobe Bryant was arguably his heir apparent, as crucial and challenging to the brand he represented — Nike — as he famously was with his Lakers teammates on the court.

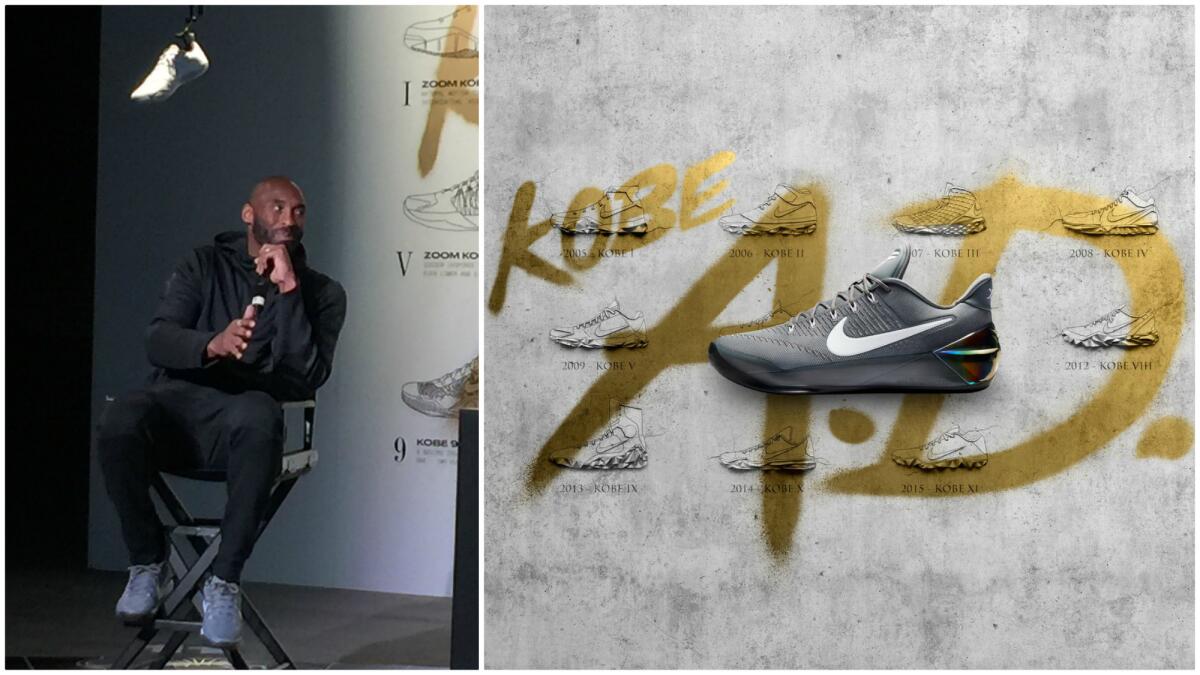

Jordan made sneakers cool, but Bryant changed the shoes themselves, creating the market in minimalist, low-silhouette footwear in a league in which everyone was still lacing up their high tops to protect their ankles.

That led to a succession of NBA superstars adopting the same lighter, quicker shoe style, which helped liberate their moves on the hardwood. It happened soon after Bryant left Adidas to sign a four-year, $40-million deal with Nike in 2003, then pushed the company to build a basketball shoe as sleek and safe as those worn in professional soccer.

Bryant’s Nike and other endorsements, NBA salary, investments and business dealings led to a net worth that Forbes estimated at $600 million or more.

The work ethic that propelled Kobe Bryant’s NBA career also helped drive his transformation into a business mogul, author and Oscar-winning filmmaker.

“Over the course of the past decade, Bryant released hundreds of colorways in partnership with Nike, many of which were fast fan favorites along with silhouettes that have become the preferred game shoe for players across the league,” online sneaker resale giant StockX said in a statement Tuesday. “Alongside Jordan, he was undoubtedly one of the most influential basketball players in the sneaker world.”

That sneaker world is now struggling with how best to respond after Bryant, his 13-year-old daughter, Gianna, and seven others died in a helicopter crash in Calabasas. In some ways, the industry is fighting against the natural inclination of fans who are hungry to buy any of their hero’s merchandise after a sudden and premature death.

In the sneaker world, there’s no precedent for this, said George Belch, an associate dean and professor of marketing at San Diego State University.

“Companies are going to struggle with where to go from here. These are uncharted waters,” Belch said. Bryant was the first sneaker superstar to meet an untimely end, he noted, “and none of these companies want to be perceived as trying to capitalize financially on his death.”

Bryant merchandise disappeared so quickly from Nike websites and shelves after Sunday’s helicopter crash that some wrongly perceived that the shoe giant had deliberately halted sales in a kind of homage to the five-time NBA champion. It hadn’t; fans had just bought it out that quickly.

Some businesses have pulled all of their Bryant merchandise indefinitely and were unsure of when, or how, they would again offer them to customers. Others decided that they wouldn’t allow any post-death price increases on Bryant merchandise.

Still others, like StockX, decided that they wouldn’t profit during a time when fans would be most frantic to pay potentially exorbitant prices for Bryant merchandise.

“In recognition of this legacy, StockX will donate all proceeds from sales of Kobe Bryant-related products (sneakers, trading cards and merch) for the week following his tragic passing to the Kobe and Vanessa Bryant Family Foundation,” the company said in its statement.

Some of these business decisions, and the reactions of sneaker collectors, offer a glimpse of Bryant’s influence and inspiration to his fans.

In Las Vegas, Jaysse Lopez, co-owner of Urban Necessities, a sneaker consignment store that also operates out of New York, had a message for those seeking to profit on Bryant’s death.

“Consignors,” Lopez said on the company website, “out of respect for his family and legacy, we will not allow price changes on Kobe items that are consigned. If you have increased prices on Kobe items, we will be reverting the price back to the original listing price.”

Those who find that stance unacceptable can request their merchandise back, he said.

In Los Angeles, Cool Kicks, a mini chain with resale stores on Melrose Avenue and three other locations, pulled more than 100 Bryant signature sneakers that had been up for sale early Sunday, said co-owner Adeel Shams, 28. Shams also was refusing to buy Bryant merchandise for an indefinite period.

“Kobe was my Michael Jordan,” Shams said, who said he grew up yelling the name “Kobe” every time he made a great shot in a game of pickup basketball.

“He was a huge motivation to me in launching my business. Profiteering off his death just doesn’t seem right,” Shams said.

In Chicago, the heart of Michael Jordan country, where his Airness led the Bulls to six NBA championships, the same sentiment toward Bryant reigns. There, Robert Mulokwa, chief executive of Arkiv, which buys sneaker collections for later resale, said he wouldn’t be dealing in any Bryant merchandise so soon after his death.

“He was probably the second-best player in the history of the league, behind Jordan,” said Mulokwa, whose all-time favorite sneaker is not a Jordan brand, but a pair of Kobe 9 Elite Gumbo League Maestros. “Purely out of respect, I’m not going to be trying to make any money off of him right now.”

For fans, the same relentless pursuit of athletic perfection Bryant expected from his teammates was an inspiration to excel in their own professional lives.

“No one else had the ferocious toughness Jordan displayed that regularly ripped the hearts out of competing players,” said sneakerhead Drew Simon, executive vice president for production for STX Films in Los Angeles.

Simon was a Minnesota Timberwolves backer whose sports fan heart was broken by Bryant’s skillful play in the 2004 NBA playoffs. “I wound up admiring and loving that drive and determination. He knew how to persevere when the deck was stacked against him,” he said.

Loyola Law School professor Hamilton Chan, who refuses to throw away any of the Kobe Bryant shoes he has bought over the years, no matter how worn, gets a regular view of Bryant’s hold on fans.

When Chan teaches or speaks, he often mentions the fact that he was a corporate transaction attorney in 1999 when he helped out on the deal in which Bryant purchased the Olimpia Milano Italian basketball team that his father, Joe Bryant, once played for.

The reaction, he said, is always the same.

“What was Bryant like? How was it to work with him?” Chan said. “It’s all people want me to talk about.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.