Ethan Brown went vegan but missed fast food. So he started a revolution

Beyond Meat is changing the way people eat. Can it live up to its founder’s wildest dreams?

Twitter co-founder Biz Stone likes to think of himself as a “not preachy vegetarian.” He doesn’t eat meat but tends to keep his views to himself.

So he was wary when asked by Kleiner Perkins, the Silicon Valley venture capital firm and a backer of his social media platform, to help vet an investment in an unusual meatless burger start-up. It was led by an entrepreneur he’d never heard of: Ethan Brown.

“My first thought was, ‘Oh boy, some kind of hippie guy who is going to preach about how mean eating animals is,’” Stone recalls thinking before the 2011 meeting.

It didn’t quite turn out that way. Instead, he met a former fuel-cell industry executive with an MBA and a sweeping business plan.

“It was immediately apparent that he was massively ambitious. So this was no novelty food thing that was going to go into the freezer section next to the silly products,” Stone says. “This was a guy who from the beginning was saying, ‘We are going to be in McDonald’s.’”

Stone returned to Kleiner Perkins with a ringing endorsement and a question: Can I get in on this too?

That start-up was Beyond Meat, whose initial public offering rocked Wall Street last year, revving up an astounding cultural shift that has put bean-based burgers on the menu at fast-food outlets better known for their industrial-grade meat and fries.

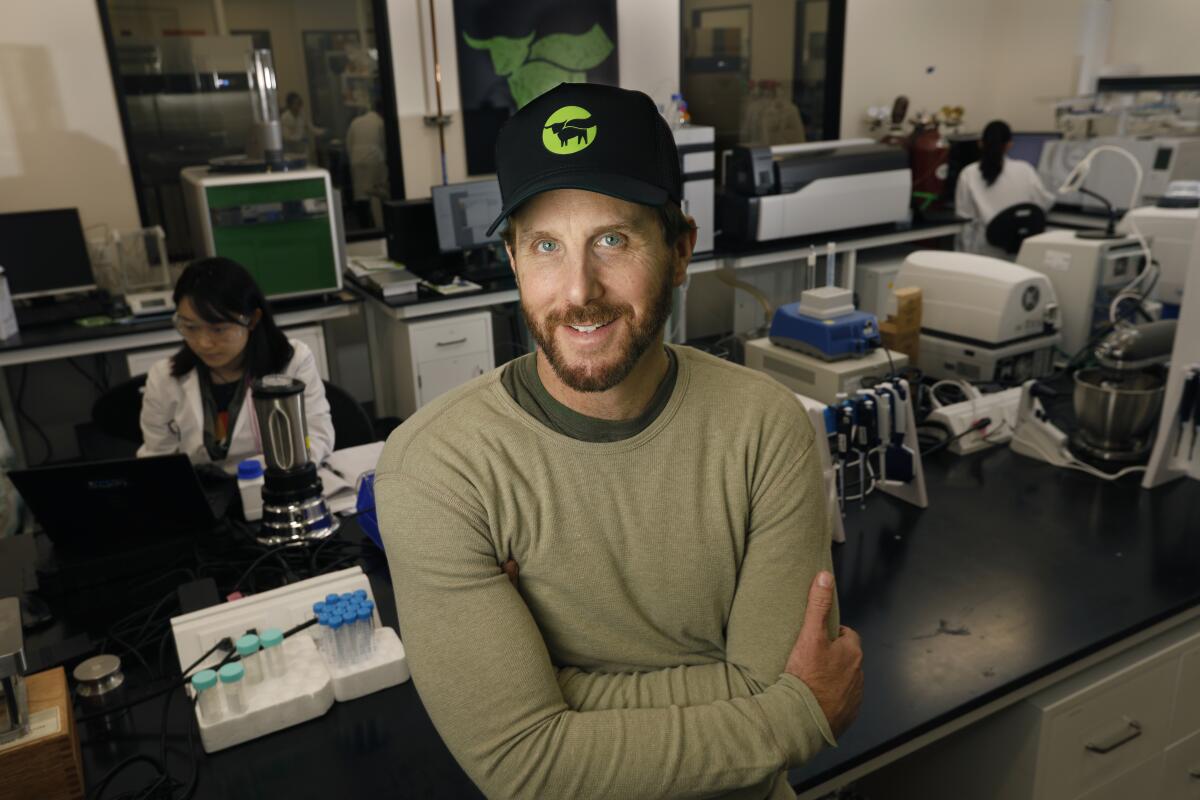

That level of change, as with any revolution, takes dreamers who can imagine a world well beyond the present, as well as pragmatists who know how to get things done. Brown, a lean and bearded 6-foot-5 vegan, is a bit of both.

The 48-year-old proselytizes a carefully calculated “flexitarian” pitch that goes down well in an age of better burgers and planetary anxiety. There is no need to avoid leather products, like he does, to get healthy and stave off global warming. People can just “eat more of what they love” — as in a Beyond Burger smothered with their favorite fixings, even if there’s still steak in their grocery cart.

Scolding customers doesn’t make sense, Brown says, when what they really need is better choice.

“I loved things like fried chicken, loved things like burgers. And then someone comes into the scene and starts telling you it’s bad for your health, bad for the environment, bad for the animals,” he says. “Everyone’s on their own journey. I ate a ton of meat. I get it.”

This mantra has sent Beyond where tofu and jackfruit have never reached, bringing Brown startling success.

The El Segundo company’s burgers are sold at Carl’s Jr., Ralphs and the hip Soho House, as well as more than 67,000 other locations globally. Those include several dozen McDonald’s restaurants in Canada after the fast-food titan on Wednesday announced an expansion of its test of its plant-based burger, called the P.L.T.

Brown himself nearly joined the billionaires club after Beyond’s May IPO, one of the most successful since 2000. Shares soared 163% above their $25 offering price on their first day of trading and kept rising, peaking at nearly $240 in July.

But the stock fell under $80 in November and didn’t make real gains until this week, the victim of Wall Street’s fickle appetite and a swarm of short sellers convinced its growth prospects have been hyped. Even Beyond acknowledges it faces “intense competition” from a long list of rivals, such as big agribusinesses and natural food makers wanting to cash in on the craze.

Impossible Foods, a Redwood City, Calif., start-up, is proving to be its toughest rival. While Impossible’s burger is available at fewer outlets — 17,000-plus restaurants and a handful of grocery chains — the company has so far made the highest-profile fast-food deal with Burger King, which introduced the Impossible Whopper nationwide in August. However, Reuters reported Tuesday that Impossible, citing supply constraints, has abandoned pursuit of a McDonald’s deal, which could trump all others.

A smorgasbord of critics is another headache. Some are skeptical of the role methane-spewing cows contribute to climate change or the value of eating plant-based burgers to combat it. Others find the ultraprocessed nature of the burgers distasteful, a reaction that has been seized upon by the meat industry.

It’s been a lot to swallow for Brown, who has come to discover a truism about being a revolutionary in any human endeavor: Make it far enough, and they come at you from all sides.

‘Analyze it to death’

The Double R Bar Burger embodies America’s culinary obsession with all things living and breathing. A signature sandwich of the Roy Rogers chain, it contains a quarter-pound beef patty, a seared slice of Smithfield ham and American cheese, all stuffed into a buttered Kaiser roll. Meat and dairy is the point. If you want fixings, add them yourself.

In middle school, it was Brown’s favorite. He’d order it at the Roy Rogers down the block from his Washington, D.C., school, until one day while waiting in line it seemed less appealing. The 13-year-old had a love of animals fostered by a rural dairy farm his father operated as a side business. It had dawned on him that his cravings were being sated by cows’ milk and butchered steers and pigs.

“I can just remember thinking: ‘This is like an orgy of animals I am eating.’ I started to feel different about it,” he recalls one day, sitting across a white laminate table at Beyond’s spartan headquarters.

Brown’s epiphany may not rank up there with Newton’s apple, but it eventually led him to veganism and a personal philosophy based on the moral implications of Darwinism that is closer to Hinduism’s respect for all living creatures than the idea that man is at the top of the food chain.

“There is no stark break between humans and the rest of life on Earth. There are gradations and degrees of difference and degrees of similarity, but you can’t sort of say ‘us-them’ in a scientific way,” says Brown, whose Playa del Rey residence is home to a menagerie of two dogs, a cat, a turtle and a potbellied pig named Wilbur. “The reason that you think that way is because you want to create something that is separate because it’s easier to exploit.”

When Brown was in his 20s he invested in Worthington Foods, which owned veggie-burger maker Morningstar Farms, and scored big when Kellogg bought it. It got him thinking about a plant-based McDonald’s — a low-cost, high-efficiency fast-food restaurant that would make such fare palatable to the mainstream. The former burger junkie missed the experience.

“I wanted to create the whole thing,” he says. “I wanted to prove that you could do it.”

But the typical veggie burger wasn’t going to cut it. Little more than beans, nuts and grains, the veggie burger aims to stand in for, not replicate, a hamburger for the meat-averse. But with only about 5% of the U.S. population maintaining a vegetarian diet, and even fewer practicing vegans, it is not a recipe for taking on the $1-trillion-plus U.S. meat and poultry industry.

Brown had a better idea. Why mash together plant foods when they can be transformed into an approximation of the real thing, attracting diners who love their Big Macs but find it hard to digest the accompanying guilt?

“The thing that I think most people didn’t capture that well is that meat is a completely knowable entity. You can unpack it. You can figure out what’s in it. You can analyze it to death,” he says. “And so, to do that and rebuild it was the approach.”

It just took him a while to figure all that out.

By the time Brown graduated from Connecticut College in 1994 with a double major in history and government and a stint on the school basketball team, he was already convinced climate change was humanity’s No. 1 problem, influenced by his father, Peter, a professor who researches how human thought systems have contributed to the degradation of the planet.

Unlike his dad, though, he decided to make a career in business, having admired the simplicity of Warren Buffett’s investment strategy since his youth. That sent him to Columbia University — where Buffett got his master’s — for an MBA. He found work at Ballard, a Canadian developer of fuel cells. But after eight years, he decided that he could make a bigger impact by trying to live out his McDonald’s dreams.

Beef is the single largest emitter of greenhouse gases per calorie among the more than 70 billion chickens, pigs, cattle and other livestock that are estimated to be slaughtered globally each year for human consumption. Fewer cattle also means less demand on water supplies and land for grazing and feed crops.

John Sheridan, Ballard’s then-chief executive, was not surprised that Brown focused on such a huge problem. “He always had that type of aggressiveness to him — a big-picture idea in his mind and a pragmatic way to kind of push it,” he said.

In his 30s, Brown invested in a vegan restaurant that served textured soy protein from Taiwan as a faux meat in, say, a Philly cheesesteak. He noticed that non-vegetarians ate it up and decided to start a business in Maryland importing it himself. Whole Foods agreed to distribute it in the Mid-Atlantic region.

But he knew the product wasn’t good enough to make anyone forget they weren’t eating meat. He eventually came across papers from the University of Missouri, where scientists in the heartland were trying to find more uses for the state’s soybean crop. He set up a visit in 2009 — and what he observed was the technology that makes Beyond Meat possible.

‘Prius for the plate’

The transformation of beans into fibrous protein is accomplished by a machine called an extruder, which is like a giant pressure cooker crossed with industrial-size food processor. Stuff in raw materials and out might come breakfast cereal, pet food or glue. It also happens to be effective at uncoiling protein molecules in beans and realigning them in ways that vastly change their texture.

Textured soy protein made through this process has been around for decades, but the end result doesn’t shred like chicken or have the mouth feel of beef. By experimenting with moisture, pressure, temperature and ingredients, Fu-hung Hsieh, a food science professor, and researcher Harold Huff created something close to meat.

“We went through a lot of failures and then finally we came up with a way that we started seeing some promise,” Huff says. “We showed it to other people besides Ethan, but Ethan was the only one who was committed enough and saw enough future in it to actually pursue it.”

Brown secured the technology license and in 2010 worked up an email pitch called “Prius for the Plate” that he sent to Silicon Valley venture capital firms. He got a handful of replies — “my inbox was not exploding” — including from Kleiner Perkins, whose investments read like a history of modern tech: America Online, Amazon, Google, Twitter, Uber.

Raymond Lane, a partner, was dubious, but he decided to fly to Columbia, Mo., in his private plane to taste the product for himself. “It had a texture and a fiber that was meat-like. And then as I took the product and tore it apart it looked like chicken,” he recalls.

It took some work to convince the other partners, who wondered about the size of the market and questioned Brown’s scant track record. “There were all sorts of skeptics about doing this,” says Lane, now a board member.

Kleiner Perkins went ahead in April 2011 with $2 million in initial financing. Stone, who has a seat on Beyond’s board, and Ev Williams, another Twitter co-founder, invested shortly after.

Brown says the importance of the venture capital firm’s decision is hard to overstate. “I was in the wilderness,” he says, having run through his 401(k)s and even his kids’ savings accounts. He went so far as to sell one of his houses.

“For a couple of years it was everything going into it. There is a lot of collateral damage that goes along with that,” he says of the entrepreneurial bug.

Even after Kleiner backed the company, Brown was tight for money. While traveling to Menlo Park, Calif., to see Bill Gates, who invested in the company in 2013, Brown had trouble getting a hotel room on his maxed-out credit cards.

Brown admits his intense focus on his business contributed to a near rupture of his relationship with his wife. However, the couple patched things up and were seen smooching when he rang the Nasdaq opening bell on the day of the company’s IPO.

In 2012, Brown moved his company to El Segundo and bought a home in Playa del Rey — deciding he wanted to be closer to Kleiner Perkins but could not tolerate Silicon Valley’s supercilious “making the world a better place” culture.

That year, Beyond built a plant in Missouri near the university and released its first in-house product, soy chicken strips sold at Bay Area Whole Foods. It later introduced other products, including a precooked frozen burger, while developing its signature offering: a fresh burger made from peas. The ingredient change required a lot of work in the lab. Brown said feedback showed consumers wanted to avoid soy, which has been the subject of conflicting health studies.

The decision was in keeping with a business philosophy that draws on Darwin too. Brown told Fortune that he’s a “big fan of failing fast and often,” calling evolution the outcome of an “unimaginable number of failures,” with winners emerging from the “wreckage of inferior models.”

Brent Taylor, a Wharton MBA who became Brown’s partner in 2011 after meeting him while consulting for Kleiner Perkins, says he experienced that approach firsthand.

“For Ethan it’s all about charging forward. That would definitely make me uneasy and annoy me sometimes for sure just because it’s not in my bones. Needless to say, looking back, I appreciate that about him,” says Taylor, 39, who left the company in 2016 with stock worth close to $40 million at Friday’s closing price of $96.07 a share.

Beyond’s big breakthrough came in May 2016 when Whole Foods Markets in the Rocky Mountain area began selling fresh Beyond Burgers in the meat section. It led to deals with other grocers — and surprising success.

Ralphs said the Beyond Burger became the chain’s No. 1 packaged patty, with sales through the end of September up more than 40% over last year. Carl’s Jr., which introduced the Beyond Famous Star in January, says some 4.4 million of the sandwiches had been sold through September, making it the most successful burger launch in more than two years even though the plant-based version comes with a premium that can top $2 in some restaurants.

Fight over ‘fake’

A Beyond Meat patty is a consequence of the most advanced science. The package lists 18 ingredients, starting with water and pea protein isolate, ending with beet juice extract (for color) and including methylcellulose (a binder) and sunflower lecithin (a lipid).

In short, it’s nothing Mother Nature has cooked up even if every substance is derived from a plant. It’s fabricated by scientists whose resumes include stints in biomedical and cancer research, food science and chemistry. Their job is simple in concept yet maddeningly complex: Make the company’s sausages, burgers and other products indistinguishable from the real thing.

That mission is reflected in the name Brown thought appropriate for the company’s food lab, expanded in 2018 to help keep a step ahead of the competition. It’s called the Manhattan Beach Project Innovation Center, an intentional allusion to the military’s crash program to build the atomic bomb during World War II. (It’s actually in El Segundo, not the posh beach city.)

The lab, across the street from an oil refinery, is jammed with scanning electron microscopes, spectrometers and the other sophisticated equipment necessary to render from plants all the necessary amino acids and transform them into meat — with far less of an environmental impact and no cholesterol.

A study conducted by University of Michigan researchers in September 2018 for Beyond Meat concluded that its burgers generate 90% fewer greenhouse gas emissions and use 46% less energy than an equivalent amount of beef. They also require far less water and land.

But at a time when more consumers are going organic, the burgers can seem alien. A box of Kraft Mac and Cheese is easier to get your head around. So it’s not surprising the slow-food movement popularized by author Michael Pollan, which advocates eating local home-cooked foods, hasn’t exactly warmed to the burgers.

Pollan has actually had kind words about Impossible’s product, but John Mackey, the vegan co-founder of Whole Foods, whose willingness to distribute Beyond’s products was crucial to its early success, called plant-based burgers in general unhealthy “super-highly processed foods” in August.

“To Michael Pollan and all that, my comment is always, ‘Not all of us live in Marin County or Martha’s Vineyard and not all of us have the knowledge or money to do that,’” Brown blurts out during an interview, unprompted by any question. “So our job here is to enable a mainstream consumer to make healthier choices in their life and do it where they eat.”

Impossible, founded in 2011 by a Stanford biochemistry professor, has found success with a soy-based burger that contains heme — an iron-rich molecule said to impart a meaty flavor — made by a GMO process. Brown “swears” Beyond’s burger is better, but Impossible’s often wins taste tests, though not all, and the company created buzz among foodies with its early strategy of focusing on hot, high-end restaurants.

A challenge for both companies is the meat industry’s deep pockets. The industry is lobbying for regulatory changes that would prohibit the burgers from being labeled meat, similar to the campaign waged by the milk industry against nut-based drinks.

In December, the Center for Consumer Freedom, a business-backed nonprofit that has mounted campaigns against soda taxes and bans on trans fats, took out full-page newspaper ads attacking the ingredients in plant-based burgers, saying, “Fake meats don’t grow on vines. They’re ultra-processed imitations that are assembled in industrial factories.”

Brown is offended by the criticism: “The automobile is not a fake horse-drawn carriage. I was on the phone with somebody in Brazil and they kept talking about non-meat meat. It’s just plain meat meat. We are building it from the same stuff, so we should be able to call it meat.”

He’s got himself tangled up in the climate debate too.

Brown has been criticized for asserting that 51% of global greenhouse emissions come from livestock, a number taken from a 2009 analysis by the World Watch Institute. That is far higher than the estimate of 14.5% of human-induced emissions calculated by the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization.

He’s taken it from all sides on the issue. One University of Oxford climate researcher told CNBC that the new generation of plant-based burgers have five times the carbon footprint of a traditional veggie burger. Brown took notice of the comment.

“How many people are eating black-bean burgers? That is like taking a Tesla, which does have a good environmental outcome relative to an internal combustion engine, and comparing it to a bike. It’s just not relevant,” he says, exasperated.

Burgers and ‘existential crisis’

Brown is talking casually in early November as he gets ready for a photo shoot when he blurts out more words of frustration. “Have you seen the stock?” he asks.

Beyond had had a great fall. McDonald’s announced it had chosen Beyond to be its supplier for a plant-based burger test in Canada. The company had reported its first-ever quarterly profit, and Dunkin’ Donuts decided to go national with a Beyond breakfast patty earlier than expected. Yet the company’s shares had been pummeled, falling more than 40% since Oct. 1.

Analysts had their concerns, including heightened competition. Burger King had announced its strongest sales growth in four years, driven by its Impossible Whopper, while Nestle had recently introduce its competing Awesome Burger.

Although Brown says he doesn’t like talking about the company’s share price — it’s “good discipline” — he had complained previously that short sellers just didn’t understand his company. “At some point I want to say: Do you believe me now? You can keep shorting, but it’s going to be increasingly painful for you to do it because this is happening.”

With this week’s stock gains driven by the McDonald’s developments, his fortunes are on the rise. Brown is worth close to $400 million when you add up his shares and options. “All of this attention right now probably makes him feel a little uncomfortable,” Lane says.

His investors have grown to include high-profile names such as NBA star Kyrie Irving, skateboarder Shaun White and Thomas Middleditch, star of the HBO show “Silicon Valley.” Middleditch said in an email that he had sought out Brown because he was looking for an investment “that might move the needle green,” and they have since become pals.

Brown, who is fond of T-shirts, jeans and Nikes even at the office, says he won’t be buying a $1-million Ferrari, something he heard a company investor had planned to do with his proceeds. “That is just not where I am going to be — ever. To take the resources you have been given and to squander them on ... material stuff is not what I would want to do,” Brown says.

He admits that getting a Tesla X, an SUV that starts around $80,000 that his wife wanted, was a “nightmare,” as it was the most money the couple had ever spent on a vehicle. “I am not comfortable with the purchase,” Brown says. He now drives the 2016 Prius she once had, but has ordered a smaller Tesla of his own.

For now, Brown remains focused on growing Beyond, which projected revenue of less than $300 million in 2019, into a “global protein company” that rivals JBS, a Brazilian company that is the world’s largest meat processor, with $45 billion in revenue last year. That goal wildly exceeds how big Wall Street thinks the company can get, but Brown says, “Our ambition is to literally be in every major continent changing the way people eat.”

Brown likes to joke that capitalist competition is great “as long as we’re winning,” but he ponders the subject. He knows he’s been successful in an economy that values growth above all — and at its core isn’t sustainable. “I have no problem with what I am doing within capitalism. Let’s put it that way. I think it can be used for good or for evil,” he says.

Brown’s father admired Henry David Thoreau’s simplicity, lack of interest in material wealth and commitment to the search for truth so much that he bestowed on his son the middle name of Walden, after the author’s most famous work. He also displayed a quote from the transcendentalist’s “Resistance to Civil Government” in the spring house of the family farm. It counsels readers not to simply trust the Bible or Constitution but to “gird up their loins” and pilgrimage to the “fountain-head” of truth on their own.

During an interview, Brown suddenly dives for his phone, does a search and hands over the quote. It’s been a lodestar that has helped chart his course in life: to trust himself and seek his own truth — and it’s led to a different path than the one taken by similarly environmentally conscious contemporaries such as Elon Musk.

Musk and Jeff Bezos are spending vast sums building rockets that could one day lift humanity off an uninhabitable Earth. Brown has poured all his resources into creating a sustainable future that includes burgers and eventually bacon and even a steak made from plants — food once routinely cleaved from animals. It’s really the only option we’ve got, as he sees it.

“I respect their efforts to go to the moon, to go to the stars. They are spending a ton of money trying to get off this Earth, figure out what’s out there and colonize it. My view is that energies are probably better focused here,” he says. “We are providing a solution to the existential crisis we are having.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.