Column: Resnicks set a record with Caltech gift, but altruism isn’t the whole story

Beverly Hills billionaires Stewart and Lynda Resnick garnered a heaping helping of adulatory publicity last week with the announcement of their record-breaking $750-million pledge to Caltech for research into climate change and “environmental sustainability.”

The donation, according to the university’s announcement, is the largest single gift it has ever received, and the second largest ever to an American university. (It’s topped only by a $1.8-billion gift from businessman and former New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg to his alma mater Johns Hopkins.)

News coverage of the Resnicks’ gift bristled with praise for their generosity and testimonials to their devotion to the cause of addressing climate change. Some articles quoted Stewart Resnick describing the donation as having arisen from a desire to serve his children and his children’s children.

There are plenty of reasons to avoid bottled water.... It’s incredibly expensive, it’s unnecessary, and it’s not as well regulated as tap water.

— Environmentalist Peter Gleick

“My grandkids … they would yell at me all the time, ‘How can you help with this? What are you doing about it?’ ” he told my colleague James Rainey. “A lot of the adults are not concerned, but the kids are concerned. And rightfully so.”

What was missing in all this coverage, or at least got buried as an afterthought, was any acknowledgment of the source of at least some of the Resnicks’ largess.

Although the $750 million represents a personal gift to Caltech rather than a corporate gift from the Resnicks’ principal corporate entity, Wonderful Co., they’re engaged through that company in some arguably unsustainable environmental practices.

A lawsuit pits a big pistachio grower against the even bigger Wonderful Pistachios company

The truth is that Wonderful’s agricultural enterprises are major users of increasingly scarce water supplies in California and elsewhere.

Its Fiji Water subsidiary, which has been turned into a lifestyle brand of bottled water through expert marketing, ships its product more than 5,000 miles to the U.S. from a Pacific island country, a trip requiring the burning of a great deal of fossil fuel (a major contributor to climate change), even though importing bottled water to the U.S. is wasteful and unnecessary.

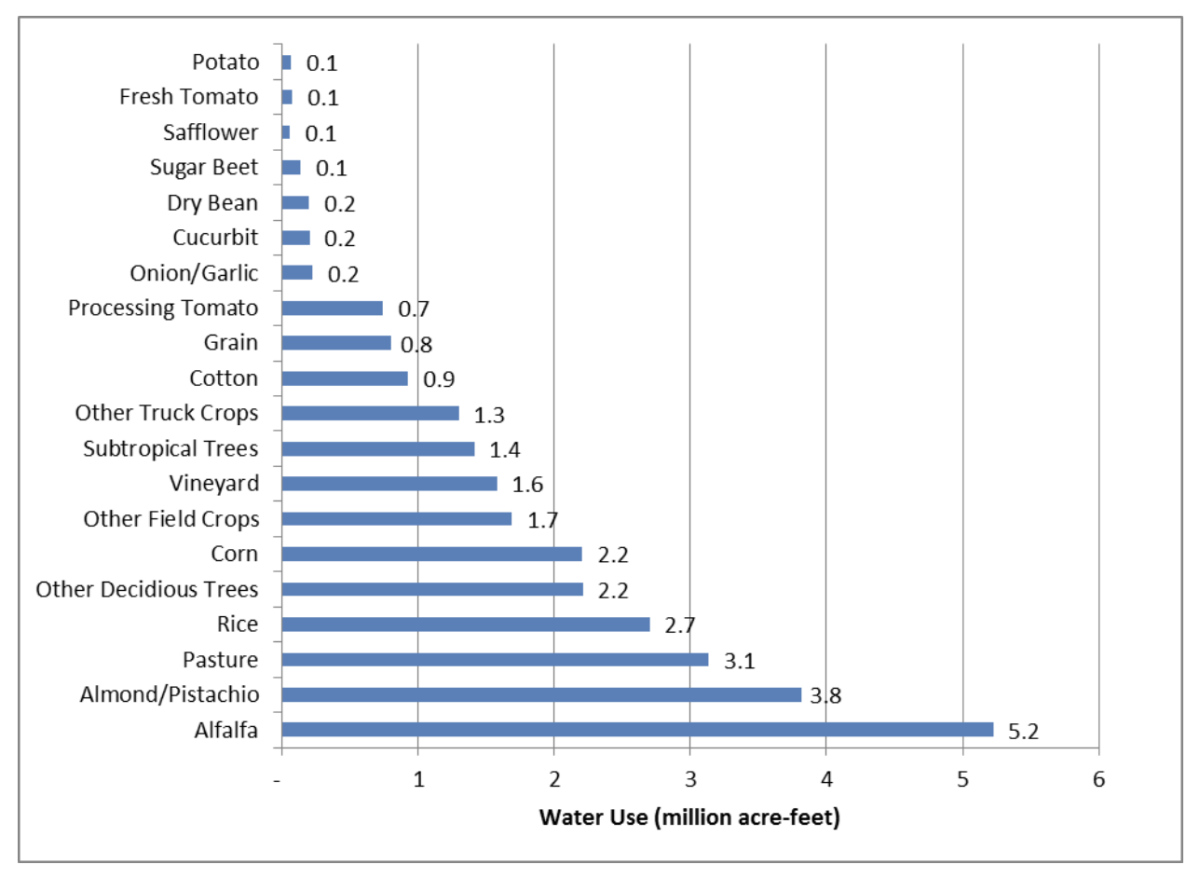

Wonderful’s almond and pistachio trees are among the thirstiest crops in California, where the availability of water is likely to shrink as a result of climate change.

And the Resnicks’ control over a key supply of water could make it difficult for anyone to craft a statewide water policy that weighs their needs against those of other users.

It would be churlish to suggest that the Resnicks’ gift to Caltech is devoid of genuine altruistic impulses; we should take Stewart Resnick at his word that he’s looking ahead to the world that the present generation will bequeath to posterity. But it would be naive to assume that altruism is the whole story.

The gift speaks volumes about the benefits that big donors receive from their philanthropy, both in this life and the hereafter, and about the economics of billionaire philanthropy itself. (The $750-million pledge won’t put much of a crimp in the Resnicks’ fortune, which Forbes has estimated at $9 billion.)

The Wonderful Company, the corporate arm of Beverly Hills billionaires Stewart and Lynda Resnick, promotes itself incessantly as an exemplar of social responsibility and a guardian of sustainable agriculture.

There’s no reason to doubt that Caltech will put this money to good use. Of the sum, Caltech says $100 million will go toward construction of a building for its sustainability resource program, $250 million will finance research immediately, and $400 million will be placed into Caltech’s endowment, which earns a typical payout of about 5%, or $20 million a year.

In announcing the donation, Caltech President Thomas F. Rosenbaum observed that the gift “will permit Caltech to tackle issues of water, energy, food and waste in a world confronting rapid climate change,” while “letting researchers across campus follow their imaginations and translate fundamental discovery into technologies that dramatically advance solutions to society’s most pressing problems.”

MIT’s obituary of donor David H. Koch lauded him for donating to cancer research, but ignored a career undermining science.

Yet one benefit that a contribution on this scale buys its donors is silence, or perhaps tactful blindness. Caltech’s announcement of the gift identified the Resnicks as “philanthropists and entrepreneurs” and mentioned the name of their company. But it didn’t specify what Wonderful Co. actually does, possibly because irony has no place in university publicity releases.

Caltech is hardly the only institution to play this game. Consider the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, which flushed the business and political records of David Koch down the memory hole in its obituary of the right-wing, climate-denying MIT donor in August.

The motivations underlying billionaire philanthropy are infinitely varied. Some appear to be motivated by a sincere desire to address problems left unsolved by governments or international organizations. The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, established by the founder of Microsoft, is focused on global health and development issues. Warren Buffett, who has pledged to give away virtually all of a fortune estimated at more than $80 billion, is focused on reducing poverty.

But it’s certainly not new for wealthy families to use philanthropy to create an image of themselves for posterity that may be at odds with their activities during their lifetimes. When the donations are large enough, the effort generally works.

The public today thinks of Andrew Carnegie as the endower of libraries, universities and a prestigious New York concert hall, not as the tycoon who played a role in the 1892 Homestead strike, a labor conflict at Carnegie Steel’s main plant that ended with the deaths of seven strikers and the injuries of hundreds more.

It’s a fair bet that future generations will associate the Resnicks with their charitable donations to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and Caltech. (They’re also active political campaign contributors, almost exclusively to Democrats.)

The ‘science’ behind Lynda Resnick’s Pom Wonderful juice

Among the Resnicks’ businesses, Fiji Water stands out for its environmental unsustainability. The couple acquired Fiji Water in 2004 for their privately held company, which was then known as Roll International and has since been rebranded as Wonderful Co.

Bottled water is one of the most wasteful manifestations of our modern throwaway culture. “There are plenty of reasons to avoid bottled water,” climate expert Peter H. Gleick, president of the Pacific Institute and a leading critic of the industry, told me a few years ago. “It’s got environmental challenges, it’s incredibly expensive, it’s unnecessary, and it’s not as well regulated as tap water.”

Transporting water in bottles to places that already have access to abundant water — such as most of the U.S. — is wasteful on a mindboggling scale.

Water is complicated.

Fiji Water’s defense, a spokesman for Wonderful told me by email, is that “ocean freight is the most economical and environmentally friendly way of transporting goods across continents.”

That merely raises the question of why water needs to be transported from Fiji to Los Angeles or points beyond at all. The spokesman also said that Fiji is “committed to achieving 20% recycled plastic by next year and 100% recycled plastic by 2025, and we are also exploring packing innovations under an incredibly aggressive timetable.” The “challenge of plastics,” the spokesman added, “is at the top of the list for researchers at Caltech” who could be funded by the Resnicks’ gift.

Of more importance in local and regional terms are the Resnicks’ agricultural businesses, particularly the growing, processing and marketing of almonds and pistachios. The Central Valley is climatically ideal for these nut trees but an atrocious location in terms of water availability. The trees require a permanent, uninterrupted supply. They can’t be fallowed in times of drought, like other crops; without water, they die.

Water experts and environmentalists are divided over whether growing almonds and pistachios in this semi-arid region is a good idea. By some measures, it makes good sense to devote scarce and therefore valuable water resources to the highest-value crops, which include almonds and pistachios. Almonds were the third most valuable California commodity in 2018, bringing $5.47 billion in cash receipts, according to the state Department of Food and Agriculture. Only dairy products and grapes ranked higher. Pistachios ranked fifth, at $2.62 billion.

“Fruits and nuts account for 45% of the total revenue of California agriculture, but consume only 34% of agricultural water, making them what Ellen Hanak, director of the Water Policy Center of the Public Policy Institute of California, has called “the only category for which the share of value is higher than the proportion of water.”

Stanford University on Wednesday announced the largest donation in its history: a $400-million gift from Nike founder Phil Knight to endow a graduate program modeled after the Rhodes Scholarships.

Wonderful says it plays only a small role in California water use: “We use one percent of California’s annual agricultural water to grow food for all of California and beyond.”

But that still places it among the top agricultural users in the state. The company says it’s “using advanced strategies like micro irrigation” and has invested “over $400 million to innovate and implement new, more efficient ways to irrigate our orchards.”

Growing nuts in an environment of scarcity requires unusual arrangements to ensure an uninterrupted water supply, and the Resnicks have been in the middle of them. The key arrangement involves the Kern Water Bank, a state-funded project that, in a highly controversial transaction still before state court, was transferred to a private entity allegedly controlled by the Resnicks.

As I reported in 2010, the water bank, a complex of wells, pumps and pipelines outside Bakersfield, was initially part of the $1.75-billion bond-funded State Water Project, which provides water for 25 million Californians and irrigates 750,000 acres. In 1995 the state gave up on the project and turned it over to Kern County water authorities. They promptly ceded it to a local consortium of public and private entities including Westside Mutual Water Co., a subsidiary of the Resnick-owned Paramount Farms.

A state judge rejected a lawsuit aimed at overturning the transfer in 2014, but the case is on appeal. No hearing date has been scheduled by the state Court of Appeal in the four years since the parties’ briefing has been completed, however.

The water bank’s private owners have maintained that they rescued the bank from a state bureaucracy that had been unable to surmount procedural roadblocks in getting it operational. Wonderful maintains that under private control, the bank is a boon to the state. “There’s a difference between using and wasting water,” the company says. “The Kern Water Bank captures and stores water runoff that would otherwise go out to sea in wet years to use in dry years.”

Yet that presupposes that water running off to the sea is wasted, which isn’t the way it’s seen by environmentalists and downstream economies such as the salmon fishery, which has suffered from the wholesale diversion of water to agricultural and residential use.

Indeed, Stewart Resnick insinuated himself in 2009 into the debate over whether the severe drought in the region should be blamed on environmental restrictions designed to help revive fisheries and river habitats. In a letter to Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.), Resnick accused federal agencies of “sloppy science” in imposing those environmental restrictions, which obviously had the potential to cut into his agricultural water supply. He demanded a new scientific study.

The National Academy of Sciences reported a few months later that the restrictions were, indeed, “scientifically justified.”

It’s fair, if perhaps impolite, to ask how Caltech researchers will deal with issues that could so intimately concern their financial patrons. There are no public indications that the Resnicks will have a say over the research portfolio or the personnel of the program they’re funding, though Caltech’s chief communications officer, Shayna Chabner, told me by email, “the gift agreement and its details are confidential.”

What’s left is a question of balance. When it comes to environmental sustainability and climate change, are the Resnicks part of the problem or part of the solution? Or both?

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.