Column: Can Trump legally revoke California’s clean air waiver? Probably not

President Trump’s latest attempt to stick his thumb in California’s eye — the revocation of the state’s treasured authority to set its own auto emissions rules — rests on very shaky legal ground, experts say.

At the very least, the move to revoke the state’s Clean Air Act waiver will lead to an intense legal battle that could delay the revocation past the 2020 election, the outcome of which could make his maneuver moot.

“The legislative history of the Clean Air Act is deep and strong, and very bipartisan,” says Sean Donahue, an attorney for the Environmental Defense Fund. “There’s no question there’s going to be an aggressive legal attack” on the revocation.

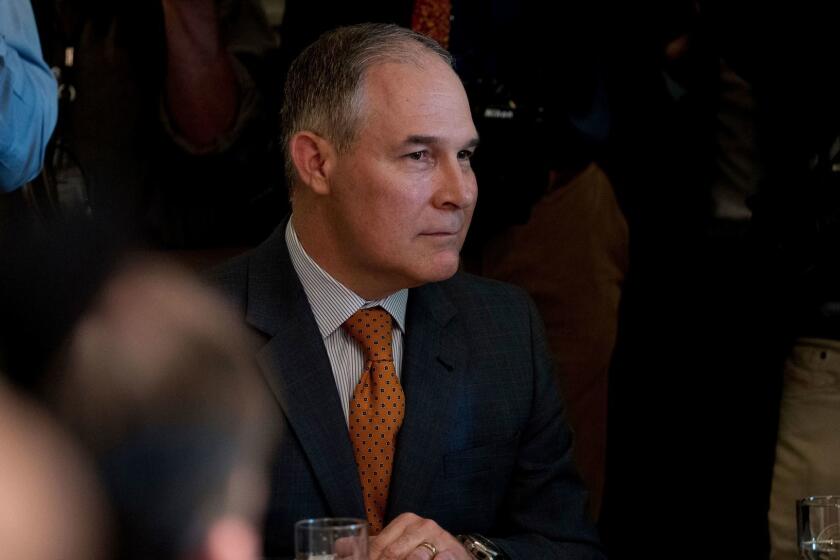

California cars have no closer link to California climate impacts than do cars on the road in Japan or anywhere else in the world.

— EPA Administrator Andrew Wheeler

Indeed, California fired the first shot in court Friday along with 22 other states, the District of Columbia, and the cities of New York and Los Angeles. Their lawsuit against Transportation Secretary Elaine Chao asks a federal court in Washington, D.C. to declare the waiver revocation illegal even before it takes effect, which would happen in about 60 days.

There’s no question that the administration is venturing onto thin legal ice by revoking the state’s waiver, which is based on authority specifically written into the Clean Air Act in 1970 and strengthened in 1977. The provision requires the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to grant California permission to set its own clean air standards as long as the state can show that its proposed standards are “at least as protective of public health and welfare as applicable federal standards” and that the state needs those tighter standards to meet “compelling and extraordinary conditions.”

Over the years, California has been granted 100 waivers, with each one typically superseding its predecessors. The most recent version was approved by the Obama administration in 2013, covering the state’s greenhouse gas emissions restrictions and its zero emission vehicle (ZEV) mandate. Both provisions would be revoked by Trump’s action.

The ZEV mandate requires major car manufacturers to produce a minimum number of ZEVs and plug-in hybrids each year or cover their quota by purchasing excess ZEV credits from electric car makers such as Tesla. The California Air Resources Board estimates that the rule will result in ZEVs and hybrids accounting for 8% of new car sales in 2025. As Friday’s lawsuit states, California began regulating auto emissions in 1959 and first instituted its ZEV standards in 1990.

Ford, Honda, Volkswagen and BMW reach deal with California regulators on fuel efficiency standards

Trump officials offered two chief grounds for the revocation Thursday. One is that the state’s emission regulations effectively take the form of fuel economy standards even though states, including California, are explicitly preempted from setting mileage standards. That authority is reserved to the federal Department of Transportation under the Energy Policy and Conservation Act, the administration says. The second ground is that California can’t show that its emissions rules are related to “compelling and extraordinary conditions” within the state.

Instead, the EPA and DOT say, the state’s rules are aimed at “national and global issues such as climate change,” environmental issues “that are not particular or unique to California.”

The most immediate problem with these arguments, legal experts say, is that the Clean Air Act does not contain any provision for revoking a waiver once it has been granted. Indeed, no waiver has been revoked in the nearly 50-year history of the Clean Air Act. The measure’s provisions set forth standards the EPA must consider to grant a waiver, but after that point nothing in the law allows it to review the grant decision.

What about the argument that only the federal government has authority to set fuel economy standards?

There was a fair amount of perplexity at the California Air Resources Board on Feb. 21, when the Trump administration abruptly announced that it had decided to “discontinue discussions” with the state’s air quality regulator over the administration’s proposal to gut federal auto emissions standards.

“What they’re saying is that even though California’s standards are not fuel economy standards but emissions standards, because a way to achieve emissions reductions is to make your cars more fuel-efficient, the emissions standards have the effect of regulating fuel economy,” says Julia Stein, an environmental law expert at UCLA. But two federal court rulings, both based on a 2007 decision by the Supreme Court, have upheld California’s regulations even though they might have an impact on fuel economy rules.

The courts found, Stein told me, that “the fact that the preemption exists on fuel economy doesn’t preempt California’s regulation of tailpipe greenhouse gas emissions.”

Trump’s strategy may be aimed at overturning the Supreme Court decision, which ordered the EPA to start regulating greenhouse gases or cogently explain why it shouldn’t. “The Trump administration would like to relitigate that whole area,” says Dan Reich, a former regional counsel for the EPA, “because they think they have a friendlier court.” (They may be right — the 2007 Supreme Court ruling was 5 to 4, with Chief Justice John Roberts and Justices Antonin Scalia, Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito in dissent. Today’s more conservative majority might overturn the 2007 precedent.)

One potentially effective defense against Trump’s revocation is that it’s based on an exceedingly threadbare scientific rationale. The action is part of the administration’s effort to roll back mileage and emissions standards established in 2012 under President Obama. Those standards mandate that overall efficiency reach 54.5 miles per gallon by 2025. Trump last year proposed ratcheting that back to 37 mpg.

The old adage about being sorry when you get what you asked for is about to land squarely on the head of the automobile industry.

As I reported last year, the administration’s published backup for its proposed rule change was laughable. The proposal stated that reducing fuel efficiency would reduce auto fatalities because (a) the more stringent mileage rules would prompt manufacturers to make lighter cars, which are more dangerous; (b) the better mileage would prompt car owners to drive more, which is more dangerous; and (c) higher-mileage cars would be more expensive, so people would stick with their older cars, which are more dangerous.

As 11 experts at leading universities, including three UC campuses, USC, Yale and MIT, responded a few months later, the analysis supporting the rollback had “fundamental flaws and inconsistencies,” and was “at odds with basic economic theory … [and] is misleading.”

They weren’t alone. American Honda issued a blistering comment in October. Honda said that the proposal “invites litigation and regulatory uncertainty, stalls long-term strategic industry planning, puts at risk American global competitiveness, exacerbates climate-related environmental impacts, and slows industry readiness for a widely acknowledged … transition to vehicle electrification.”

Like other critics, the company took issue with the administration’s claim on automotive safety. If the government used the proper math, Honda said, it would be clear that the original standards made driving safer than the new proposal.

Few federal agencies would entirely escape the meat cleaver in President Trump’s proposed budget, but none is facing more devastating cuts than the Environmental Protection Agency.

Nevertheless, EPA Administrator Andrew Wheeler and Transportation Secretary Elaine Chao pushed this discredited argument during a news conference Thursday announcing the waiver revocation. The less stringent standards would make new cars cheaper, encouraging Americans to replace their older, more dangerous vehicles, Wheeler claimed, without evidence.

On the whole, Wheeler and Chao made a host of unintelligible arguments. Chao suggested that California was trying to “impose its policies on everybody else in our whole country.” That’s a bizarre assertion, given that California doesn’t have the power to force any other state to follow its lead, and that 13 other states and the District of Columbia, accounting for about 40% of the nationwide auto market, have voluntarily signed on to California’s rules.

So too have Honda and three other carmakers (Ford, Volkswagen and BMW of North America), which have agreed with California on a plan to raise average fleet mileage to 50 mpg by model year 2026. Instead of hailing the initiative as a worthy advance on the environmental front, which would be a grown-up reaction, the Trump administration has opened an antitrust investigation of the four companies, which is the way a petulant infant would react.

Wheeler acknowledged that California “has uniquely bad problems with smog-forming pollutants” and that “there’s a direct and tight link between California cars and their emissions ... and the impacts they have on California.” Yet he also denied that California needs its standards to meet “compelling and extraordinary conditions.”

His point seemed to be that smog has nothing to do with greenhouse gases — “California cars have no closer link to California climate impacts than do cars on the road in Japan or anywhere else in the world” — so California should just concentrate on reducing smog and back off from any broader ambitions.

Indeed, it’s the quality of scientific thinking like this that could be the biggest roadblock to Trump’s getting his way. “The rulemaking record for the [2013] action was far more robust,” Stein told me, “and there’s plenty of evidence in this rulemaking record that contradicts the action the administration is taking now. So there are strong grounds for California and others to challenge the administration here.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.