Column: Justice Gorsuch’s call for ‘civility’ is a hypocritical defense of privilege

Calls for “civility” in public discourse always should come with a warning label.

That’s because they’re never what they seem. They seem to be appeals for, well, civilized behavior in debate. What they are, in reality, are appeals for submission and tacit acquiescence, directed by established authority to the subjugated.

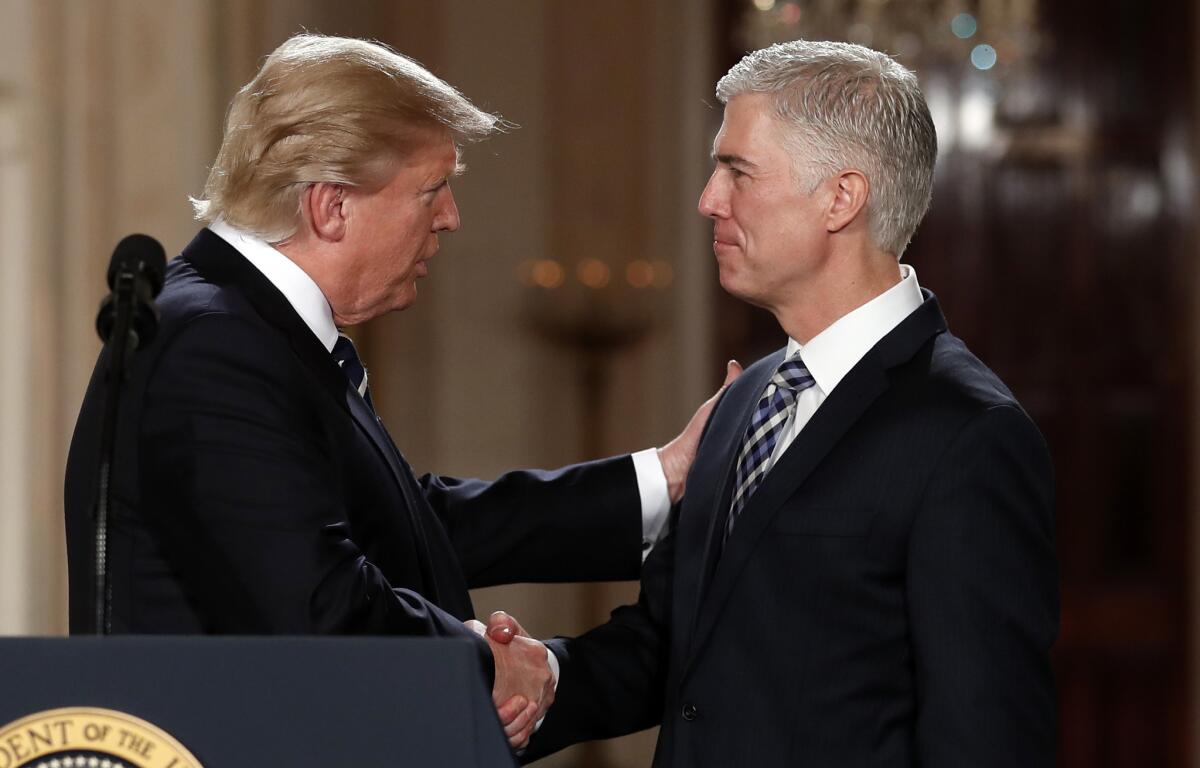

That’s the context in which one should consider the latest voice arguing for “civility.” It comes from Supreme Court Justice Neil Gorsuch, a card-carrying member of the court’s conservative majority. Gorsuch has been on a publicity tour for his new book, “A Republic, If You Can Keep It.”

The Negro’s great stumbling block in the stride toward freedom is... the white moderate who is more devoted to order than to justice.

— An uncivil Martin Luther King Jr., 1963

As reviewers and interviewers have pointed out, in the book — actually a collection of essays and articles — Gorsuch flogs the “civility” theme hard.

“I worry that, just as we face a civics crisis in this country today, we face a civility crisis too,” he writes. “Without civility, the bonds of friendship in our communities dissolve, tolerance dissipates, and the pressure to impose order and uniformity through public and private coercion mounts. ... Self-governance turns on our treating each other as equals — as persons, with the courtesy and respect each person deserves — even when we vigorously disagree.”

And: “To be worthy of our freedoms, we all have to adopt certain civic habits that enable others to enjoy them too.”

Here we go again: As Trump administration policies become ever more intemperate and inhumane, critics of those policies are being counseled to become more “civil” in their criticisms.

These are classic tropes from the mountaintop. They treat the fraught political battle over our essential freedoms — about decisions made in Washington and in statehouses across the country that can determine whether some people will live or die — as though it’s a theoretical exercise in a debating club, with a trophy and medallions as the only stakes. Only someone whose daily life will scarcely even quiver however the battle turns out could possibly take this view. Someone like, say, Neil Gorsuch.

Before delving a bit more deeply into Gorsuch’s viewpoint. Let’s take a look at how the “civility” argument has been wielded in the recent past.

Lately it’s been invoked against restaurant personnel or patrons who resent having to serve or share a public space with political figures who have made a career out of depriving them of their rights or whose general behavior in office seems beyond the pale.

Former Trump spokeswoman Sarah Sanders was asked to leave a restaurant when its LGBTQ workforce objected to her service for the president, who has made curtailing LGBTQ rights a cornerstone of his administration. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell and former Homeland Security Secretary Kirstjen Nielsen were similarly discommoded at mealtime in public settings. Stephen Miller, the architect of Trump’s openly racist anti-immigration campaign, was hectored at a Mexican restaurant, though he stayed to finish his meal.

When someone in power praises the principle of free speech, it’s wise to be on the lookout for weasel words.

The “civil” take on these episodes was that it was unfair to subject the targets to inconvenience, notwithstanding their egregious policymaking. “Let the Trump team eat in peace,” pleaded the Washington Post’s editorial page, possibly on the grounds that equal opportunity to enjoy a sociable meal is on a par with the equal opportunity to vote, to be educated and to have secure employment regardless of race, creed or sexual orientation.

Prior to that, Nicholas Dirks, then the chancellor of UC Berkeley, stepped into a quagmire when he marked the 50th anniversary of the Free Speech Movement on that campus by asserting, “We can only exercise our right to free speech insofar as we feel safe and respected in doing so, and this in turn requires that people treat each other with civility. Simply put, courteousness and respect in words and deeds are basic preconditions to any meaningful exchange of ideas.”

Dirks got hit with an uncivil reaction from critics who properly interpreted the call for civility as a weaselly dodge around the principle of free speech. As Ken White of the group legal blog Popehat observed: “Civility is an admirable value. ... But speech need not be civil to be entitled to robust protection. Berkeley’s free speech movement did not seek to protect civil speech; the Vietnam War was not an occasion for civility.”

One problem with calls for “civility,” as I noted in connection with the Sanders affair, is that the term has no fixed definition. That makes it useless in defining the boundaries of public discourse. As we’ve observed before, one person can be deeply affronted (or claim to be) by language that another finds perfectly innocuous.

Bullies are usually quick to start whining when things don’t go their way.

Indeed, sometimes the tribunes of “civility” use the term to mask their own incivility. Consider the masterly performance of Rep. Tom McClintock, R-Elk Grove, after he was recorded scurrying out of a meeting with angry constituents in his Northern California district, escorted by police. Many of the attendees had come to urge McClintock not to vote to repeal the Affordable Care Act, on which they depend for their healthcare.

A few days later, a rattled McClintock hoisted the civility flag on the House floor. “If your love of our Constitution is greater than your hatred of our president, I implore you to engage in a civil discussion with your fellow citizens,” he said. “That is what true democracy looks like.”

He then proceeded to label members of the district audience as “the radical left” and attributed the protests at the meeting — which police said were peaceful — to “a well-organized element that came to disrupt.” In an earlier interview, he described the protesters as “an anarchist element.”

“Civility” is often invoked to excuse official behavior that violates the right of free speech. When the University of Illinois wanted to fire professor Steven Salaita after he tweeted some critical thoughts about Israel’s conduct in Gaza, then-Chancellor Phyllis Wise tried to weasel out of the controversy with the humbug of claiming that Salaita’s offense lay not in what he said, but his uncivil way of expressing it.

Calls for “civility” are employed to stave off political discussions likely to prove extremely discomfiting for one side. It’s the implicit theme in the gun lobby’s position that the aftermath of a violent slaughter is the wrong time to inject “politics” into the gun rights debate. The argument seems to be that, while the blood of massacred 6- and 7-year-olds is still draining from their bodies, no one should rise up in fury at the cynical refusal by our political leadership to stop the bloodshed.

There is no better example of the corrosive effect of money on American politics than the spending of the National Rifle Assn.

Why? Because calling them to account at a moment when it matters would be impolite to — to whom? The shooter? The senators and members of Congress and presidents who allowed the carnage to be endlessly repeated? “Thoughts and prayers,” they’re “civil” and therefore acceptable. Action, that’s “politics” and therefore out of bounds.

The blindness of “civility” advocates to the fatuousness of their own works never ceases to amaze. Of all people, President Trump has argued for a new “tone and civility” in politics. During a campaign rally last October in Charlotte, N.C., Trump said, “Everyone will benefit if we can end the politics of personal destruction. ... It is time for us to replace the politics of anger and destruction with real debate about the issues.”

Yes, Trump, who attacks his political challengers with racist slurs. His definition of “civility” must come from a lexicon different from that used by the rest of the world.

That brings us back to Gorsuch, whose concept of “civility” seems especially upside down. He treats “civility” as if it’s a precondition to debate — “Self-governance turns on our treating each other as equals — as persons, with the courtesy and respect each person deserves — even when we vigorously disagree.”

Of course, the very point of the noisiest and most impolite political battles is exactly that one side hasn’t been treated with “courtesy and respect.” During the civil rights movement of the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s, African-American activists sat in at lunch counters where they had been refused service, refused to give up their seats on city buses to white passengers, and marched to demand equal rights.

These activities were the definition of uncivility, because “civility” had been defined for them by the white power structure. The most eloquent deflation of the “civility” idea was written by Martin Luther King in 1963, from a cell in the Birmingham jail where he had been deposited for leading a demonstration that was judged by the white power structure as disorderly and “untimely.”

The Red Hen affair continues to percolate through our national discourse.

King had heard the call to be civil and timely all his life. He rebuked the white clergymen to whom he addressed his letter for sounding the same call.

“You deplore the demonstrations that are presently taking place in Birmingham,” he wrote. “But I am sorry that your statement did not express a similar concern for the conditions that brought the demonstrations into being. ... Frankly, I have never yet engaged in a direct-action movement that was ‘well timed’ according to the timetable of those who have not suffered unduly from the disease of segregation. For years now I have heard the word ‘wait.’ It rings in the ear of every Negro with a piercing familiarity. This ‘wait’ has almost always meant ‘never.’”

King concluded that “the Negro’s great stumbling block in the stride toward freedom is not the White Citizens Councillor or the Ku Klux Klanner but the white moderate who is more devoted to order than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice; who constantly says, ‘I agree with you in the goal you seek, but I can’t agree with your methods of direct action.’”

He might have been speaking directly to Neil Gorsuch, who lectures us that “to be worthy of our freedoms, we all have to adopt certain civic habits that enable others to enjoy them too.” In other words, argue for your rights, but don’t overstep the bounds of good taste and decorum.

Has there been a moment in recent American history in which words like these sound more threadbare? Every day the Trump administration assaults the rights and interests of those seeking asylum from violent gangs abroad, of LGBTQ citizens, of Americans dying for lack of health insurance, of immigrants and their children, of the victims of gun violence, of those who value clean air and clean water, of women who want the freedom to make their own reproductive health decisions.

And Trump and Gorsuch have the gall to suggest that the problem in American society is that those pushing back against these policies aren’t polite enough?

Gorsuch writes in his book that “civics and civility [are] essential ingredients to civilization.” He’s wrong. The essential ingredient to civilization is equality. And that’s under attack on Capitol Hill, in the White House, and in the Supreme Court’s own chambers. Asked by the Associated Press to comment on President Trump, the most disrespectful, unmannerly and boorish president in living memory, Gorsuch replied, “If you’re asking me about politics, I’m not going to touch that.”

How civil of him.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.