Column: Insurance firms’ blunders on long-term care insurance create disaster for millions

Jeffrey Gerber has had a front-row seat for the unfolding disaster in the long-term care insurance business.

The Century City insurance broker not only sold the policies to numerous clients but became a customer himself. Now, a decade or more after the policies — which provide daily payouts to cover expenses for assisted living or nursing care — were first written, he and some 26 clients have been hit with increases in their monthly premiums of as much as 80%. That’s forcing the policyholders to make a harsh choice. “You’re forced into accepting the increase in premium or a reduction in benefits, which amounts to the same thing,” Gerber told me.

Gerber and his wife, Gayle, were each entitled to about $200 a day in benefits from Genworth Life Insurance Co. once they needed assistance. But they will have to give up an automatic inflation-related increase in their potential daily benefit if they want to keep their combined monthly premiums at the current $345, instead of swallowing an increase to $621.

There’s no way in hell that folks, as they get into fixed incomes, are going to be able to handle these rate increases. The very reason for long-term care insurance has been negated.

— Insurance broker Jeffrey Gerber

As Gerber told an official of the California Department of Insurance in April, Genworth executives had assured him repeatedly “not only was Genworth safe, but that their reserves were such that all claims could be paid easily. This was a lie.”

Genworth, which was spun off from General Electric Capital in 2004, is the largest carrier in the long-term care insurance market, but it has incurred losses averaging about $425 million a year over the last five years, according to Thomas McInerney, its CEO. The company hopes that the rate increases it’s seeking over multiple years will finally put the insurance line on a solid financial footing, McInerney told me.

Some business blunders can be fixed or reversed — think of Coca-Cola’s rollout of New Coke, followed quickly by its reversion to Classic Coke, in the 1980s. But some deliver enduring pain. Long-term care insurance is in the second category.

These four charts trace the sudden improvement in health coverage for individuals in Obamacare

But Genworth is not alone in feeling the pain from sales of long-term-care policies, especially those sold in the 1990s, the heyday of the LTC insurance market. Insurers have lost billions of dollars on those policies — Genworth’s accumulated losses through 2005 alone were $3.6 billion, McInerney says.

Among the entities that dug themselves into a hole is CalPERS. The huge California public pension fund sold some 150,000 policies to its enrollees and family members starting in 1995. In 2012, it decided to jack up rates by about 85%, phasing in the increase in 2015 and 2016. A class-action lawsuit covering 85,000 policyholders who were entitled to annual benefit increases to protect against inflation asserts that the premium hike amounts to a breach of contract. That’s because they were promised from the beginning that their rates would never rise because of the inflation provision. One named plaintiff, Sacramento resident Holly Wedding, 71, paid $58 a month for her coverage when she bought her policy in 1995; the 2015 increase raised her monthly rate to more than $304, according to the lawsuit.

The lawsuit could cost CalPERS as much as $1 billion in damages, estimates Michael Bidart, an attorney for policyholders. CalPERS believes it can show at trial that the 2012 increase was permissible under the policies, and necessary, CalPERS General Counsel Matthew Jacobs told me by email: “The only reason CalPERS raised rates was because the sustainability of the long-term care insurance fund depended on it.”

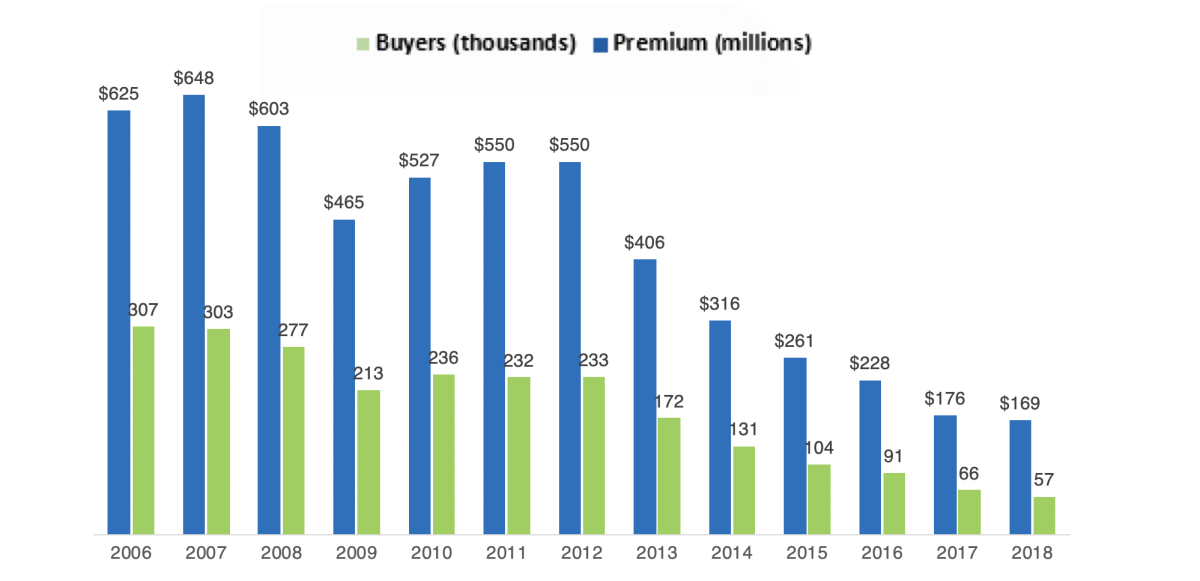

Although policies to cover the costs of a nursing home or assisted living date back to the 1970s, insurers started to market them energetically to baby boomers in the early 1990s, topping out at more than 700,000 per year in 2001 and 2002. The pitch was that as this generation aged, care in their twilight years would become monstrously more expensive. The argument was that they owed it to themselves to protect themselves from having to turn to Medicaid, the only government program that covers nursing care and now covers 6 out of 10 nursing home residents, and to shield their heirs from the burden of private long-term care.

About 7 million policies remain in force, according to the insurance research firm Limra. Sales have fallen off sharply since the peak, however. Only about 57,000 were sold in 2018, with much skimpier benefits than the originals. Scores of companies scurried into the market in the 1990s, but only about a dozen remain.

As workplace wellness programs have gained popularity among employers, questions about their effectiveness and drawbacks have proliferated.

The marketers were right about one thing: Old-age care has become ruinously expensive, with the cost of long-term care running to $100,000 a year or more. But the companies’ actuarial projections were way, way off.

For one thing, the actuaries projected that the companies would earn 7% to 8% a year from investing premiums. The existing financial models those figures were based on, however, were overturned by the realities of the financial markets, including a devastating crash in 2008 and an environment of low interest rates in the 21st century that prevents insurers from meeting those expectations. Some insurers promised customers annual 5% increases in benefits, even though inflation has run closer to only 2% a year.

Insurance actuaries, furthermore, had no experience to turn to for help projecting the behavior of long-term care policyholders. In the words of Los Angeles County Superior Court Judge William F. Highberger, who is presiding over the CalPERS lawsuit, CalPERS and other insurers have “learned a bitter lesson: Actuaries do not always make correct predictions about the true cost of insuring a new class of risks.”

Actuaries based their estimates on the disability insurance market, the closest analogue they could come up with. But the two lines of insurance turned out to be very different.

Their expectations were that policies would lapse at a rate of about 5% a year — that is, policyholders would abandon their policies for a variety of reasons, leaving their paid premiums behind to subsidize policies remaining in force. But long-term care insurance buyers turned out to be a more determined and farsighted group. At Genworth, McInerney says, the lapse rate is only 0.7%, which seems to be close to the industry average. That means many more policies remain in force than the industry expected.

During a meeting of the CalPERS board in Monterey on Jan. 19, board member Bill Slaton took the floor to launch an extraordinary attack on one of his colleagues.

Finally, the actuaries miscalculated how long customers would continue to make claims. Although they accurately projected the incidence of such ailments of old age as Alzheimer’s, they expected that patients would last only two to four years in nursing care. Instead, families have tended to keep their loved ones at home as long as possible — often at insurers’ expense — before their conditions worsen to the point where they need to be sent to a nursing home. So they start making claims earlier, and live longer. “It’s not unusual to see Alzheimer’s claims go seven to 10 years,” McInerney says.

Insurers didn’t wake up to the triple whammy of low investment returns, underestimated lapse rates and unexpectedly long-lived claims for decades, when customers reached their 70s and 80s and began filing claims. By then it was too late for insurers to institute a sequence of modest premium increases, and the era of shock increases began.

That’s not to say that problems in the market were entirely unforeseen. As early as 1987 the General Accounting Office warned that the lack of actuarial experience had made it difficult for insurers to price the policies reliably, and that partially as a consequence, some policies were riddled with loopholes. The category eventually acquired the reputation of a black hole of insurance company bad faith. Lawsuits proliferated alleging that insurers denied claims from policyholders based on nonexistent prerequisites, such as that home health care be provided by a licensed professional or that the claimant be medically, not just functionally, impaired.

What quickly became clear was that two policy provisions were especially costly to insurers — unlimited lifetime benefits, and automatic benefit increases to account for inflation. Buyers who opted for those coverages paid extra for them, but not enough to make them profitable.

Indeed, insurers let customers know that they could moderate or even eliminate the premium hikes by giving up either or both, or abandoning other benefits. Genworth has told Gerber, for instance, that he and his wife could avoid their premium increase almost entirely by removing the inflation protection.

The suspicion persists, however, that the insurers intentionally sought steep premium increases to produce “shock lapse,” which Highberger described as “a process by which insureds react to a drastic price change by dropping the coverage entirely.” The underlying injustice, moreover, is that policyholders may have been led to believe that they would face modest premium increases at most, but that the benefits they had paid for would be secure. Now they’re facing steep premium hikes if they want to keep their original benefits. Many are already in retirement.

“There’s no way in hell that folks, as they get into fixed incomes, are going to be able to handle these rate increases,” Gerber says. “The very reason for long-term care insurance has been negated.”

The government hasn’t been much help. “Long-term care insurance is very poorly regulated,” says Harvey Rosenfield of Consumer Watchdog, an expert on insurance abuse.

CalPERS and the other insurers say they need steep premium increases to keep out of insolvency, an outcome that could mean the end of benefits for thousands, if not millions, of customers. Much of the discussion in Highberger’s courtroom was about whether forcing CalPERS to stick to its original premium commitment would be a “suicide pact,” since it could not fund the product at the lower premiums.

Highberger already has ruled that the CalPERS contract language bars it from raising premiums to cover the costs of inflation protection. But he says premiums can be raised for other reasons. He has ordered CalPERS and the plaintiffs to try negotiating a settlement; otherwise he will hold a trial starting in October. The plaintiffs are amenable to a negotiated deal, Bidart says.

Highberger also urged CalPERS to seek a bailout for the long-term care insurance fund from the state Legislature, but that’s unlikely, since the pension system explicitly promised legislators in 1995 that it would be self-sustaining and never require funding from the state.

Is there still a place for long-term care insurance? Probably. The expense of long-term care will continue to rise, and so will the population requiring it. The Census Bureau says America will have 98.2 million residents over 65 by 2060, of whom 19.7 million will be 85 or older. Using today’s more trustworthy actuarial projections, the insurance industry has put lids on inflation protection increases and lifetime benefits, while pricing new policies for profit. But the tendency to surprise customers with policy restrictions that kick in only after they’ve paid premiums for 20 or 30 years may never disappear. Insurance regulators should pay attention, and stay busy.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.