Column: New data show that failing to expand Medicaid has led to 16,000 unnecessary deaths

Adversaries of Medicaid expansion have always pointed to the lack of evidence that enrollment in Medicaid improves health and saves lives, and therefore the expansion is a waste.

A new study should put that argument to rest, permanently. The researchers found not only that the expansion of Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act brought appreciable improvements in health to enrollees, but also that full expansion nationwide would have averted 15,600 deaths among the vulnerable Medicaid-eligible population.

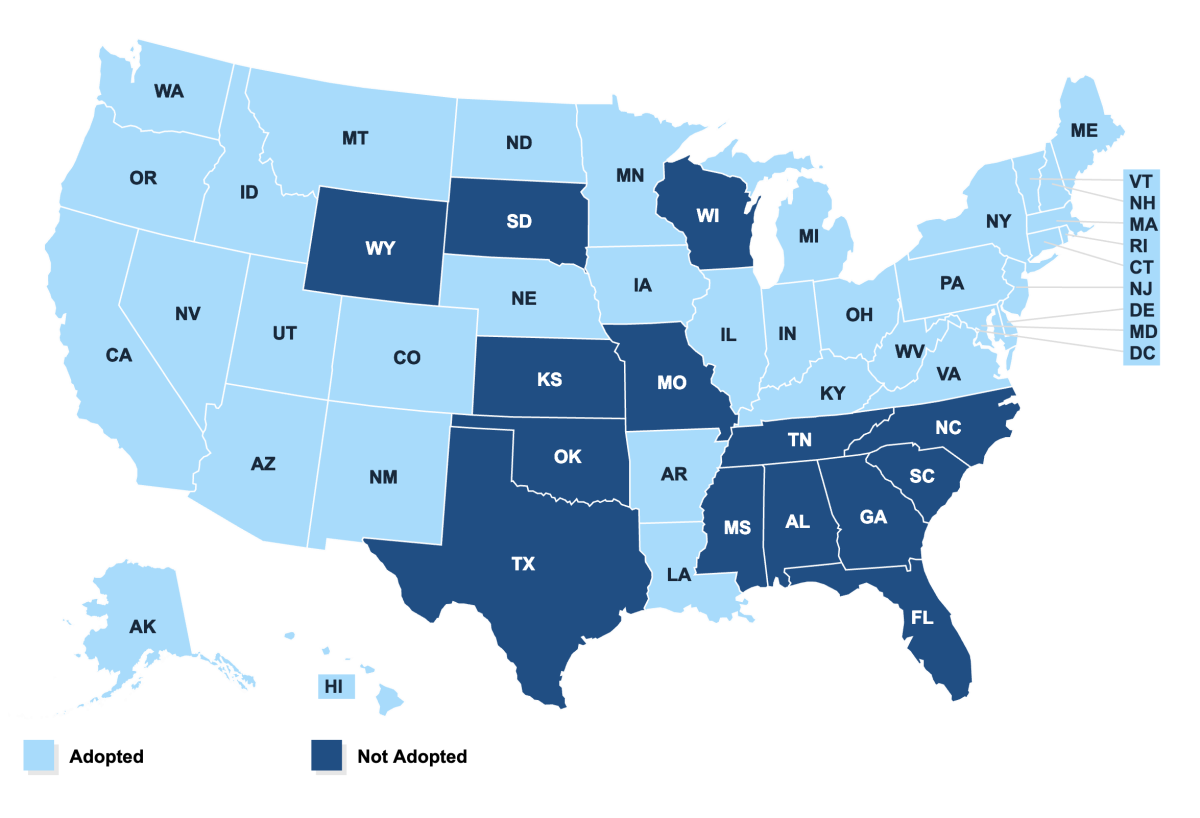

In other words, the 22 mostly red states that refused to accept expansion starting in 2014 caused 15,600 unnecessary deaths among their residents. “This highlights an ongoing cost to non-adoption that should be relevant to both state policymakers and their constituents,” write the study’s authors, charitably. Fourteen states are still holding out.

Medicaid expansion has been a litmus test for Republican governors and legislative leaders aiming to demonstrate their anti-Obamacare bona fides. They’re mostly in Deep South states and some havens of warped concepts of “freedom” such as Wyoming and South Dakota; some states such as Maine and Louisiana adopted expansion more recently when they replaced GOP governors with Democrats.

This highlights an ongoing cost to non-adoption that should be relevant to both state policymakers and their constituents

— Miller, et al

The authors of the new paper, a team led by Sarah Miller of the University of Michigan’s business school, recapitulate the sorry history of Medicaid expansion. The Affordable Care Act originally imposed it nationwide, with a provision that the federal government would pick up 100% of the expansion cost in its first three years, declining in stages to a permanent 90% share, where it stands now. That’s much more than the federal share of the traditional joint federal-state program, which covers mostly low-income households with children. The ACA expanded that to all households, including childless single persons and couples, earning less than 138% of the federal poverty level (or $17,236 for a single).

The expansion mandate was overturned by the U.S. Supreme Court in a 2012 decision by Chief Justice John Roberts. Possibly trying to strike a compromise that would allow him to uphold the constitutionality of the ACA as a whole, Roberts made the expansion voluntary state by state.

Republicans who think the American public is clamoring to repeal or roll back the Affordable Care Act have another think coming.

Since then, conservatives have worked hard to depict Medicaid as ineffective. They’ve done so by overinterpreting limited studies such as a 2013 study of a Medicaid expansion in Oregon. Critics focused on the researchers’ finding of “no significant improvements in measured physical health outcomes in the first 2 years” of expansion, but they overlooked the findings that the expansion did “increase use of healthcare services, raise rates of diabetes detection and management, lower rates of depression, and reduce financial strain.”

Conservative health policy commentator Avik Roy, for example, crowed that the result “calls into question the $450 billion a year we spend on Medicaid, and the fact that Obamacare throws 11 million more Americans into this broken program.”

This sort of poison extends even to Seema Verma, a Trump functionary who despite being director of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services has argued that the expansion hasn’t been a success despite its enrollment figures and has been a leader in undermining the program by allowing states to impose premiums, work requirements and punitive disenrollments on patients. (Her efforts have been blocked by a federal judge, for now.)

Other studies have shown measurable success in health outcomes from Medicaid expansion. One study cited by Miller’s team found a significant 8.5% reduction in mortality among patients with end-state renal disease after they enrolled in Medicaid. Another found a “decrease in rates of cardiovascular disease among adults ages 45-64 associated with state adoption of the ACA Medicaid expansions.”

Miller’s study focused on mortality rates among a sample of nearly 600,000 subjects who were aged 55 to 64 in 2014 and would be eligible for Medicaid under expansion--that is is, with income below the ceiling. They calculated mortality rates for the sample population starting in 2008. They found that mortality rates for the entire sample were consistent (and rising) until 2014, when expansion began. As Miller told me, “at the time the Affordable Care Act was implemented, they started diverging. Mortality rates went down in the states that expanded and continued climbing in the states that didn’t.”

Failure to expand in the holdout states, the researchers conclude, “likely resulted in 15,600 additional deaths ... that could have been avoided if the states had opted to expand coverage.”

The contest for worst Cabinet member of the Trump administration is what we might call “competitive.”

Their findings, they assert, tend to confirm “robust evidence that Medicaid increases the use of healthcare, including ... prescription drugs and screening and early detection of cancers that are responsive to treatment.”

As the researchers point out, it should be “obvious that Medicaid would improve objective measures of health.” The lack of empirical data has allowed naysayers to claim that the program doesn’t work. That’s an ever-harder argument to make. It’s time for the critics to give it up.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.