L.A. is working on major zoning code revamp

Los Angeles passed a law last year requiring bicycle racks within 50 feet of the front door of many new buildings. But a problem surfaced immediately: The federal Americans With Disabilities Act requires handicapped parking spaces with an easy path to the door clear of things like bikes.

The conflicting requirements — one in the city’s building code, the other in its zoning code — left developers in a quandary, said Craig Lawson, a land use consultant who’s seen several clients stumble on the rule. They could redesign the entryway of their building — no small task — or seek a variance to put the bike parking elsewhere, a costly process that can take months of hearings.

“Most projects try to avoid filing a variance unless absolutely necessary,” he said. “It’s the sort of thing that just needs to be fixed.”

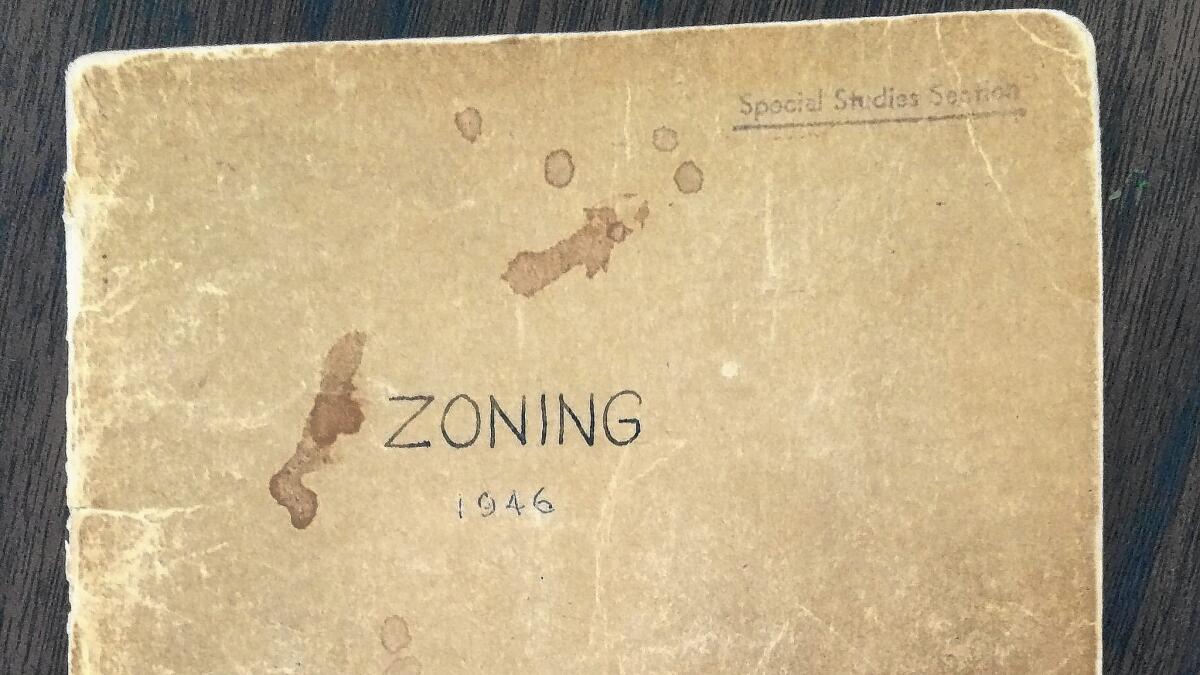

The two rules — both well-intentioned but at odds — are just one of countless contradictions embedded in Los Angeles’ zoning code, the 800-plus-page document that governs what can be built where in the city, and what it should look like.

City planning officials are hoping to iron them out by rewriting the 70-year-old code, with an eye to making development here more predictable, less expensive and more in tune with the needs of a modern city.

“[The code] has become this vast, unwieldy system,” said Alan Bell, deputy director of the city’s Planning Department. “There’s a lot of utility in making it more understandable.”

The project, called Re:Code LA, won’t be finished until at least 2017, and its results may take years to filter out into the city’s 35 community plans. But a series of recommendations — big-picture goals and priorities — is heading to the City Council soon. If the members approve, planners will spend the next three years doing a line-by-line revamp of the codes and the rules they carry.

Zoning is the DNA of a city. It lays out what businesses can go where, what streets look like, how far your wall is from the sidewalk. L.A.’s, written in 1946, encouraged the ingredients of the postwar boom years: single-family houses, streets built for cars, separation of home and work. More modern approaches to development — “mixed use” projects, or turning an old warehouse into office space — often must jump through hoops to fit the code.

“We have a 1946 code for a 2014 city,” said Tom Rothmann, who’s spearheading the project for the Planning Department. “We’re trying to do all these progressive things but we don’t have the tools in place. It’s like trying to play an MP3 on a Victrola.”

To keep up, the code has been patched and amended countless times over the decades, swelling from 96 pages when first written to more than 800 today. Special districts carrying their own zones cover 60% of the city, and in some places stack five deep. The basic R-1 zone for single-family residential comes in more than 300 flavors. Contradictions abound, and interpretations vary.

Navigating all this drives up the cost of development in L.A., say builders and planners. A cottage industry of lawyers and consultants exists to parse the code. “Expediters” will walk a project through the permitting process, for a fee. Applying for variances and special permits can add months to a development timeline.

“Opening a corner Starbucks before 7 a.m. requires a conditional use permit,” said Edgar Khalatian, a land use lawyer with Mayer Brown who’s co-chairing the recode project’s advisory committee. “That means $20,000 to $30,000 in application fees, six months of process and hiring an architect and expediter. It just doesn’t make sense.”

Cleaning up some of the more arcane elements of the code — like the 1980s provision requiring stores on a corner, but not on the interior of a block, to get a special permit to open before 7 — should make it easier to do business, Khalatian said, especially for small businesses and contractors who don’t have the resources to hire pricey experts.

And it could enable better-quality development across the city, said Will Wright, director of government affairs at the Los Angeles chapter of the American Institute of Architects.

“There’s a limited amount of resources,” he said. “Money spent going through this Byzantine maze is money not spent on making things more beautiful and useful.”

The project has bigger aims too.

The code can be a tool to help the city achieve some of its policy goals, Bell said, by streamlining approvals for affordable housing, for instance, or making it easier to develop dense neighborhoods around transit stations, reducing the need to drive, and thus air pollution.

“To the extent you can be strategic about how you use those levers, zoning controls do kind of shape and guide investment decisions that grow the economy but also provide some public goods,” Bell said.

The city should tread carefully if it plans to use zoning as a tool for policy change, said veteran developer Mott Smith. If Los Angeles wants to build more affordable housing, he said, the best approach is to increase funding for affordable housing. Zoning’s good for encouraging better design and preventing “gross incompatibilities” in a neighborhood, Smith said. But that should be the extent of it.

“The most important thing is to set our expectations appropriately,” Smith said. “If your goal in rewriting the zoning code is to correct market failures or create a more fair society, then you should hang it up and go home, because you cannot do that.”

Another thing this project cannot do is actually rezone the city.

The code will streamline zones and may create new ones, but deciding how they’re used is up to the 35 community plans that cover neighborhoods around the city. As those are updated, a few at a time, they’ll incorporate the new tools. Crafting community plans is an often-contentious process that typically takes years. But it means any big changes to existing neighborhoods will come not from City Hall but from the people who live there.

For better or worse, that will blunt the impact of the new code, said Andrew Whittemore, a professor of city planning at the University of North Carolina who’s studied L.A.’s zoning.

“I’d be shocked if I ever saw a single-family zone upzoned to anything else,” he said. “That’s never going to happen.”

Still, the project is a rare chance to redraft the outlines of Los Angeles for a new generation, said Mark Vallianatos, a member of the advisory committee and director of the Urban and Environmental Policy Center at Occidental College. The old code still reflects the vision of the postwar generation that wrote it, and that generation’s vision of a good life, he said. But the city has come a long way since then.

“Now we have a chance to update that vision,” he said. “We can ask: What’s a good life in the city of Los Angeles today?”

Twitter: @bytimlogan

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.