Rent vs. buy? A look at the math and other factors

It may be the biggest financial decision most of us ever make: Buy a house? Or keep renting?

For a while in the wake of the housing crash, the answer was pretty clear: If you could swing it, buy now.

But things have changed rapidly. Prices in Southern California have climbed by a third in two years. The post-crash bargain bin has been picked clean. Yet doubts linger about the health of the housing recovery, and the broader economy.

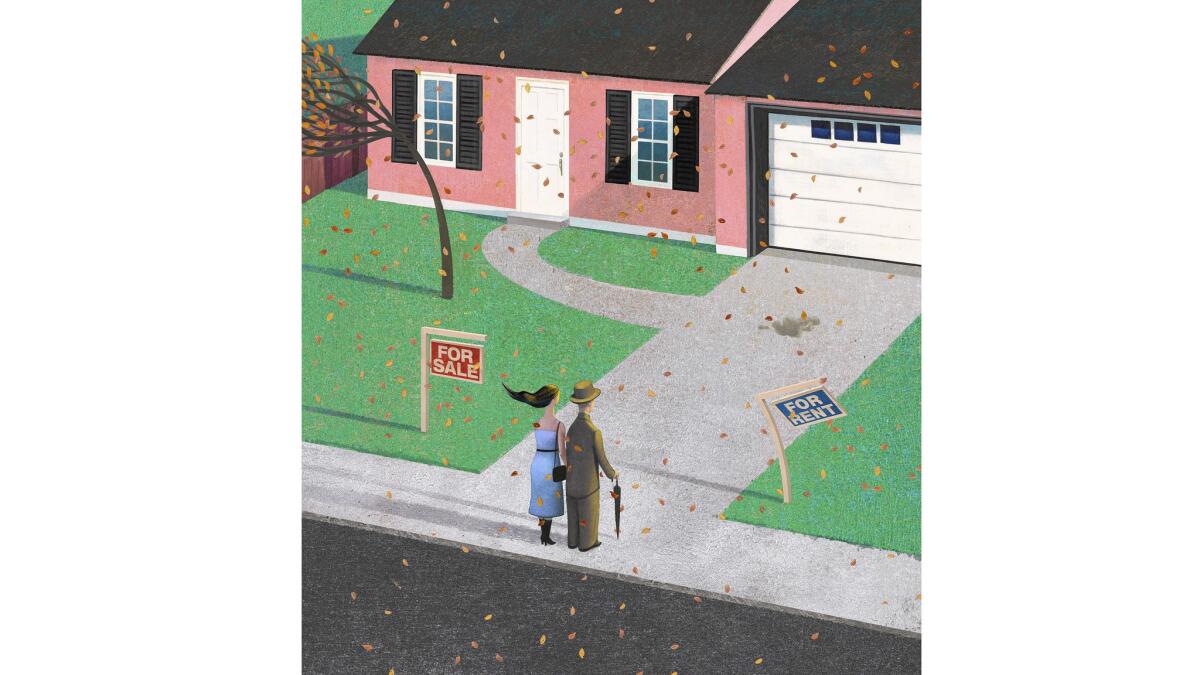

That has a lot of would-be home buyers eyeing the market more carefully. They’re weighing the new higher prices against interest rates still near record lows, deciding between the flexibility of renting and the potential long-term payoff of homeownership. And many are looking at a job market that still feels a little wobbly and wondering whether now is the right time to take the plunge.

All this is one reason why home sales in the Southland fell 10.4% through the first half of the year, according to figures from CoreLogic DataQuick. Even as buyers are shaking off the effects of the recession, they’re confronting prices that are no longer very recessionary at all.

“People still have this idea that houses are still more affordable, which, compared with their highest points before the crash, they are,” said Natalie Lohrenz, director of counseling at the Consumer Credit Counseling Service of Orange County. “But they’re getting out of reach again for a lot of our typical clientele, which is middle-income people.”

Still, despite the dents of the housing crash and the new higher prices, survey after survey of renters suggest that most do plan to buy. The question is when.

In some ways, it boils down to simple math, the kind Jed Kolko does all the time.

The chief economist at Trulia, Kolko regularly produces a Rent. vs. Buy Index for 100 markets across the U.S., including L.A.

Crunching home prices, rents on comparable apartments, interest rates, tax deductions and other factors, he tries to determine the spread between the cost of buying and the cost of renting.

The last time he did, in February, he projected that buying would cost 24% less than renting for the typical household in Los Angeles County over seven years. In Orange County, it would cost 21% less. But, he notes, prices have been climbing faster than rents, and the next time he crunches the numbers, he expects those figures will be smaller.

“The gap [between buying and renting] will continue to narrow,” he said. “It’s already been narrowing.”

As it does, would-be buyers will have even more to weigh, like location.

Southern California includes many housing markets, from foreclosure belts like Lancaster and San Bernardino — where sale prices remain relatively cheap compared with rent — to high-end areas like San Marino and Newport Beach where seven-figure houses have bounced back from the crash but rents remain relatively modest.

“Prices are real high in some places, compared to rent, and in some places they’re real low,” said Gary Smith, a Pomona College professor who’s written a book about the economics of homeownership. “It’s hard to make a universal statement like, ‘Everyone in Southern California should buy a home.’”

Some of this dynamic, too, lies in what’s getting built where.

Parts of Southern California are seeing something of a rental boom. In places like downtown Los Angeles and North Hollywood, swanky new apartment buildings are going up left and right, but there’s little supply on the for-sale condo market.

That’s a big change from 10 years ago, said Enrique Wong, regional manager in Marcus and Millichap’s Los Angeles office. Back then, multi-family development was about half for-sale, half for-rent. Now it’s overwhelmingly rental.

“There’s a lot of risk inherent in developing condos,” Wong said. “A lot of developers struggled through the downturn of 2008 and 2009 and they’re a little more careful with regards to putting up new condo developments.”

That’s driving up the cost of what condos there are, while all the apartment competition keeps a bit of a lid on rental prices. Still, there’s lots of demand for nicer rentals — even at $2,000 or more a month for a one-bedroom — from young people with good jobs and no particular urgency to buy.

Travis Ruff sees them often. A real estate agent with Coldwell Banker, Ruff sells a lot of condos in Studio City and North Hollywood and owns six rental properties himself. Whereas some clients come in set on buying, he knows lots of other people for whom it’s just not on the table.

“It’s just a different mind-set,” Ruff said. “They don’t want to own. They don’t want the hassle. But they’re paying $3,000 a month for an apartment and they could easily buy a condo for that.”

Indeed, even the most likely first-time buyers are holding off.

A recent study by lending giant Fannie Mae found that the homeownership rate among “prime” first-time buyers — married couples in their early 30s with a college degree, a child and household income of at least $95,000 — fell by more than eight percentage points from 2006 to 2012. When those people move, only a bit more than half now are buying a house, the study found, compared with three-quarters of them six years prior. This is despite homes being relatively cheap for some of those years.

There are financial reasons for this — tight lending requirements, high student debt, an unsettled job market — said Pat Simmons, director of strategic planning in Fannie Mae’s economic research group. But some of it, too, stems from a changed perspective after the housing crash. The idea that a house is always a good investment got thrown out the window.

“Baby boomers saw a decline of nearly $1 trillion in home value during the bust,” Simmons said. “Younger folks saw that experience among their parents. I think that’s going to leave an impression.”

That may be a healthy thing, said Lohrenz, if it keeps people from stretching too far to buy a house on the assumption that its value will catch up. Many would-be buyers figure they can make the mortgage payment, but they don’t necessarily budget for all the other stuff — taxes, condo fees, maintenance costs — that go along with homeownership, not to mention the transaction costs of buying and selling a house if you plan to live there just a few years.

“The biggest challenge for us is helping people be really realistic,” she said. “A big part of the housing crisis was people not knowing what they were getting into.”

But even for those who are well-prepared, the decision to jump in can be daunting.

Cedric Shen and his wife have been “aggressively looking” for a house to buy for about three months, but they’ve yet to put in an offer. They’ve looked all over, from Eagle Rock to Redondo Beach, but haven’t found anything they really like at a price that seems right.

“We’re fully qualified for a loan. We’ve got good credit and no debt. You’d think it would be easy,” he said. “But you’ve got inventory issues, and you’ve got prices that seem ridiculous.”

They could stay in the one-bedroom apartment they rent in Marina del Rey, at least for a while. But Shen missed the chance to buy low a couple of years ago — he was paying down law school debt and his wife was getting an MBA — and now he’s worried that prices and interest rates will climb higher. On the flip side, though, Shen’s a self-employed attorney, and worries a bit about what might happen if business sags or the housing market starts falling.

“We’re anxious to do it,” he said. “There’s just so many factors involved.”

Twitter: @bytimlogan

Receive business updates. Sign up for the business newsletter here.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.