Downtown L.A. development spreading south with planned SoLA Village

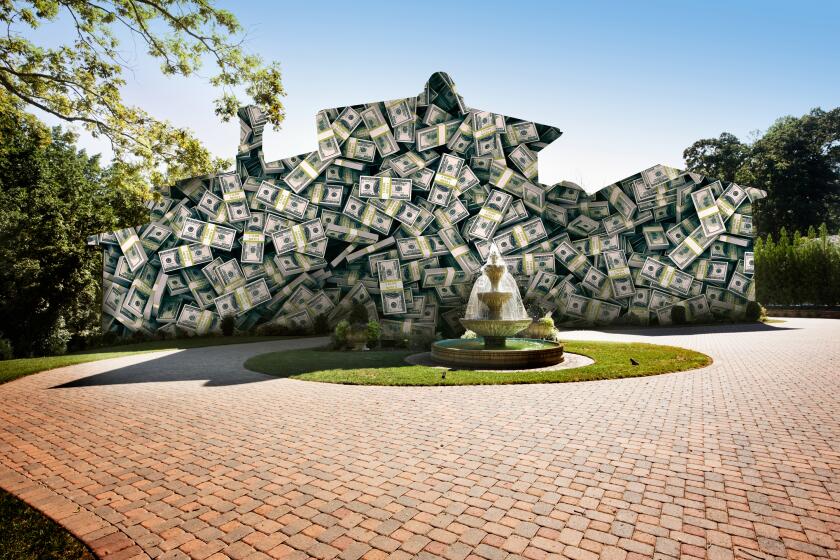

A $1-billion residential, hotel and retail complex is being planned south of the 10 Freeway in downtown Los Angeles as robust development promises to spread beyond the traditional boundaries of the neighborhood.

The proposed project, called SoLA Village, would rise just south of Washington Boulevard on a block and a half next to the former LA Mart, a large design center and showroom for the gift, interior design, and home furnishing industries.

Now known as the Reef, the high-rise built in the 1950s also provides incubator space for new creative firms and artists. The planned project would be an ambitious addition by its owners into two parking lots covering 7.5 acres on both sides of Broadway.

Plans call for a densely developed complex with skyscrapers and low- and mid-rise residential buildings along with outdoor plazas and terraces intended to create a pedestrian-oriented community.

“SoLA Village will be about place making,” said Ava Bromberg, head of operations for the Reef and the SoLA Village project. “With the Reef, we are turning creative space into more of a community and connecting that community to the surrounding neighborhoods.”

Bromberg oversaw development of Atwater Crossing, a mixed-use complex in the Atwater Village neighborhood of Los Angeles that incorporates housing, offices, manufacturing, a restaurant and live theater in an environment intended to nurture young firms in creative fields.

Both projects are controlled by limited liability companies headed by Ara Tavitian, a Glendale physician who invests in commercial real estate.

The developers hired well-known architecture firm Gensler to come up with the design for SoLA Village that will be submitted to city officials for approval.

“We’re not looking at this project as a singular fingerprint,” said Shawn Gehle, a design principal at Gensler. “It’s multiple projects within one project with diverse forms and materials.”

Plans call for a 1.66-million-square-foot development to be built in stages, probably starting with a 19-story, 208-room hotel. Guests might include people doing business at the Reef or attending events at the Los Angeles Convention Center.

The other tall structures would be condominium towers of 35 stories and 32 stories. There would also be multiple shorter apartment buildings. The breakdown of for-sale and for-rent units would be 900 condos and 549 apartments including 21 “live-work” units for people who operate small businesses at their homes.

There would be shops, restaurants, bars and a grocery store. Like most new residential projects, SoLA would have a gym and yoga studio — and it would have an art gallery. There would be 2,734 auto parking spaces and 1,300 bicycle parking places that would help support a bike-sharing program. The developers hope the bikes will encourage people to use the adjacent Blue Line light rail on Washington Boulevard.

By erecting tall, slim buildings, the developers hope to preserve views of the downtown skyline for people living south of SoLA while leaving much of the site clear of structures. Plans call for significant open space, emphasized by two landscaped central plazas facing Broadway. There would also be courtyards, patios and terraces with outdoor seating, cafes and public performance spaces.

“We need to break down expansive, urban blocks to achieve a pedestrian scale,” Gehle said. Steps and a wide footpath would lead from the Metropolitan Courthouse across Hill Street from SoLA Village through two blocks to Main Street.

Billions of dollars’ worth of real estate development have taken place north of the 10 Freeway in recent years, and more is on the way, but comparatively little investment has been seen on streets south of the busy interstate during downtown’s recent renaissance.

“This is a ‘not seen’ neighborhood,” Bromberg said, usually overlooked by investors.

But perceptions can change, she said. The South of Market district of San Francisco that is now a thriving hub of technology businesses and the artsy Chelsea neighborhood of New York were considered declasse not long ago.

“Los Angeles is a very dynamic, open-minded city in terms of the people we attract,” Bromberg said. “The freeway underpasses can start to disappear” as psychological barriers.

The neighborhood has the chance to evolve as a lower-cost alternative to downtown, where land costs are high, said Rob Katherman, head of planning and economic development for City Councilman Curren D. Price, who represents the 9th District where SoLA is proposed.

“Downtown has become very expensive. It’s no cheaper to live downtown in an apartment than it is on the Westside,” Katherman said. “I think this is a natural progression.”

The development proposal still has to pass through an approval process expected to last about three years that would include multiple public hearings. “There are certainly a lot of details that need to be worked out,” Katherman said, “and they need to get the community and stakeholders onboard.”

Still, the councilman’s office is “thrilled” at the prospect of such substantial privately funded development in the area, he said.

“This is a wonderful opportunity to show what the future of downtown is going to be as it migrates southward.”

Twitter: @rogervincent

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.