Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac to go after more strategic defaulters

Anyone thinking of skating on mortgages owned by either Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac may want to think again. As a result of new government reports, the two companies say they are going to do a better job of going after so-called strategic defaulters.

Fannie and Freddie can pursue judgments against borrowers who walk away from their loans even though they have the ability to make their payments. That’s called a strategic default, and many borrowers are taking that step — typically throwing in the towel because their homes are no longer worth as much as they owe.

But when their homes are sold at foreclosure and the proceeds are not enough to cover their outstanding loan balances, it creates a deficiency for which many defaulters either don’t realize they are liable or don’t care.

To date, the two government-sponsored enterprises, which are now highly profitable after five years of running in the red, haven’t done a particularly good job at pursuing deficiency judgments, according to scathing reports from the Office of the Inspector General at the Federal Housing Finance Agency.

But the FHFA says it is going to make the GSEs clean up their acts. And that should serve as fair warning to those who can pay but fail to do so.

As the inspector general’s office says time and again in the reports, chasing down strategic defaulters can not only cut the enterprises’ losses on bad loans but can also “serve as a deterrent to those who would chose to strategically default on their mortgage obligations.”

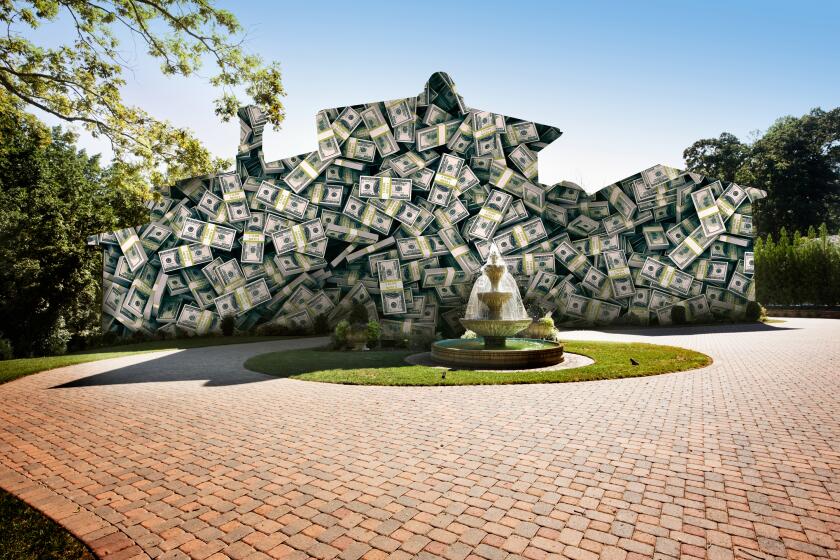

Going after strategic defaulters is big money. According to the report by the inspector general’s office criticizing Freddie Mac’s lax practices, the company has left billions on the table.

The report found that Freddie Mac, which has received some $71 billion in taxpayer assistance since it was taken into conservatorship by the FHFA in September 2008, did not refer nearly 58,000 foreclosures with estimated deficiencies of some $4.6 billion for collection by its vendors.

Of course, only a percentage of that amount might have been recoverable because some borrowers are simply tapped out. But because the bad loans weren’t even considered for recovery, Freddie Mac “eliminated any possibility” for collecting what is owed, the report said.

Now extrapolate that to Freddie Mac’s entire holdings and you can see we’re talking some really big money here. As of December, the big secondary mortgage market company had nearly 50,000 foreclosures still on its books, carrying a value of some $4.3 billion. And as of March 31, it held 364,000 mortgages that were 60 days or more delinquent and were, therefore, likely foreclosure candidates.

Fannie Mae’s portfolio of troubled assets is much larger. At the end of last year, it owned more than 105,000 foreclosed properties valued at $9.5 billion and carried a “substantial” shadow inventory of 576,000 seriously delinquent mortgages that were 90 days late or more and likely to end up in foreclosure.

It does a better job than the smaller Freddie Mac, according to the inspector general’s office. But in a separate report, Fannie Mae earned a slap on the wrist for not taking any action on nearly 30,000 accounts because statutes of limitation had expired or were about to. For the same reason, the report says, it failed to pursue deficiencies of some 15,000 accounts that already had been reviewed for collection by its vendors.

Several factors influence the decision to pursue deficiency recoveries. But most important, state laws dictate timelines for filing claims. Some states do not allow deficiency judgments at all, but they are fair game in more than 30 states and the District of Columbia. But 10 have short windows — only 30 to 180 days in which collections are allowed.

But not going after defaulters where it is permissible to do so not only reduces the chances of recovering potentially billions, the reports point out, it “incentivizes” other borrowers to walk away from mortgages they can afford to pay.

The new inspector general reports are a follow-up to one issued a year ago that called the FHFA, the agency that oversees Fannie and Freddie, on the carpet for failing to provide enough guidance about effectively pursuing and collecting deficiency judgments wherever and whenever possible.

In September, in response to a draft of these latest reports, the agency set down requirements for both enterprises to maintain formal policies and procedures for managing their deficiency collection processes, establish a set of controls to monitor their collection vendors and comply with state laws in an effort to preserve their ability to pursue collections.

And by the first of the year, the FHFA said it will begin to more closely monitor the effectiveness of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac’s deficiency judgment processes. That’s government-speak for “We’ll be watching you from now on, so you’d better get your collection house in order.”

Distributed by Universal Uclick for United Feature Syndicate

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.