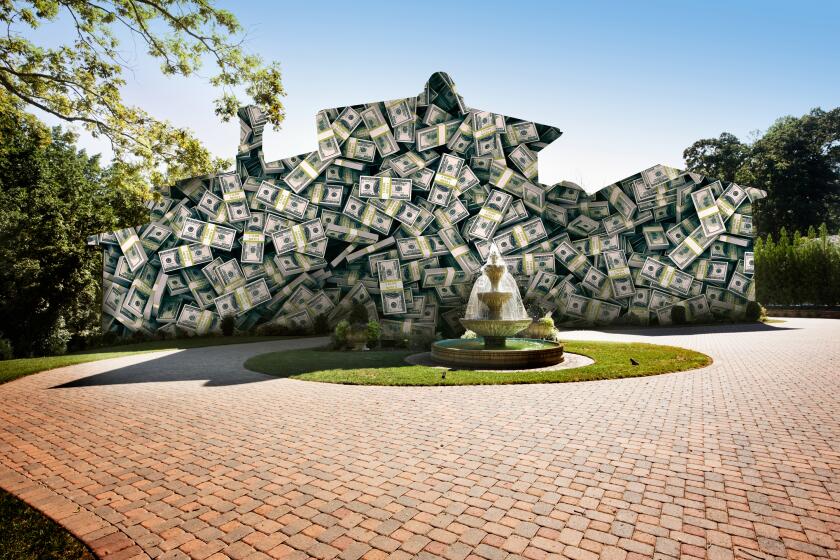

California’s unemployment benefits fund is mired in debt

SACRAMENTO — Late payments, glitch-prone computers and swamped call centers aren’t the only problems bedeviling California’s unemployment insurance program.

The insurance fund that pays state jobless benefits — run by the Employment Development Department — owes nearly $10 billion to the federal government. That’s because the state has been paying far more in jobless benefits than it receives in employer-paid taxes, and the feds make up the difference.

“The whole system is really whacked out right now and needs a fix,” said Assemblyman Curt Hagman (R-Chino Hills). “Every time you peel off a layer of this EDD, there’s an additional problem waiting to be tackled.”

Hagman is vice chairman of the Assembly Insurance Committee, which last week held an oversight hearing into the EDD’s operations.

California has been wrestling with its unemployment insurance debt for almost five years, and now it projects that the debt won’t be repaid for at least a decade. That’s unless Gov. Jerry Brown’s administration and the Legislature come up with a new way to pay for the employer-financed program.

At least three stabs at finding such a solution have failed since 2004, with the last attempt failing this year.

“We can’t keep putting our heads in the sand,” said Angie Wei, a lobbyist for the California Labor Federation. “The problem is not going to go away by itself.”

About 466,000 Californians currently receive state-paid unemployment benefits. The average weekly benefit is about $300; the maximum, $450. Recipients are required to actively seek employment.

Employers pay state and federal unemployment-insurance taxes. The state’s unemployment insurance fund finances the first 26 weeks of jobless benefits, and that’s the fund that is insolvent — largely because tax revenue has been insufficient to cover the sharp rise in claims that began with the recent recession.

In addition, federally funded benefits extending past 26 weeks are scheduled to expire at the end of the year unless renewed by Congress.

The state had hoped to pay back the federal government as the economy got better, but no dice, officials said recently. The debt is so large, a recent EDD update warned, that “the current financing system cannot self-correct during better economic times ... even if disbursement levels were to reach pre-recessionary levels.”

The blunt assessment, EDD spokeswoman Loree Levy said, was intended to spur policymakers, economic interest groups and politicians to reach agreement on how to balance the fund. “It’s got to be fixed,” she said, “or we take another dive when we hit another recession.”

In the meantime, each year California employers have to forgo hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of federal tax credits, which are reduced when the state cuts its repayments to the federal government. And their federal unemployment tax bill could more than quadruple in 2015 compared with the 2012 level, the EDD forecast said.

State taxpayers, meanwhile, are saddled with the interest payments on the debt to the federal government. The state has paid $871 million in the last three years and will pay an estimated $431 million in the next two years, the EDD said.

Much of that interest had to be paid with other borrowed money: $612 million from the state disability insurance fund, which comes due in 2016 and 2017.

There’s no mystery about how to right the fund, analysts say.

Employers, who provide 100% of the funds for the state safety-net program, could increase contributions. California is one of a handful of states in the nation that levy the payroll tax on only a worker’s first $7,000 of annual income.

Alternatively, laid-off workers could get lower payments or be excluded from benefits by tightening eligibility requirements. Or, there could be some combination of the two.

For now, groups representing employers and labor, separately, have shown interest in talking with the governor’s staff about trying yet again to cut a deal.

“The administration will continue to push all parties to work together to stabilize the fund,” said Jim Evans, a Brown spokesman.

But getting business owners and lawmakers to pass a tax increase during an election year “is a tough sell,” said Allan Zaremberg, president of the California Chamber of Commerce.

Zaremberg and other employer groups are not confident of reaching an agreement that can win support from two-thirds of the members of the state Senate and Assembly.

“I don’t see the political will to do it,” said Bill Dombrowski, leader of the California Retailers Assn.

This year, an employers coalition proposed refinancing the federal debt by selling state bonds to be retired out of current unemployment tax revenue. The governor’s office, which has been working to pay down what Brown calls the state’s “wall of debt,” did not embrace the idea.

“It appears to be a non-starter,” Dombrowski said.

At the same time, business also put forward a list of 23 proposals, similar to those in other states, that in various ways would reduce unemployment benefits and make qualifying for them more difficult.

“There’s no appetite for taking away benefits or eligibility for laid-off workers,” said Wei, the California Labor Federation lobbyist. “Our average weekly benefit is $300. Who can live on that?”

Twitter: @MarcLifsher

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.