Tech sector faces challenges if the stock market slide continues

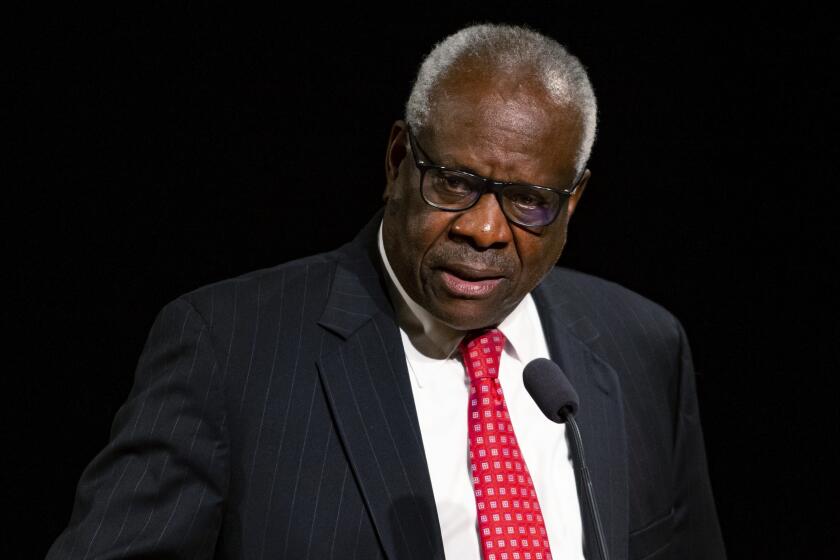

The stock market slide could lead to fewer initial public offerings by tech start-ups. Above, GoPro CEO Nick Woodman, center, celebrates his company’s IPO in June 2014. The firm is growing fast on the backs of U.S. consumers — where demand remains strong.

Last week’s stock sell-off could upend an already confusing landscape for the U.S. technology sector.

For a while last week it appeared tech stocks might escape relatively unscathed, even as the broader market headed down. But Friday’s 3.5% loss for the Nasdaq composite index put the leading technology exchange into the red for the year, down 0.6%.

If stocks continue sliding this week, that could put a drag on investments in technology companies, which have been strong this year. Acquisitions could pick up as initial public offerings slow.

The coming weeks should help determine whether the outlook is as bleak as some fear for start-ups, venture capitalists and tech stock investors. Here’s a look at some of the key questions.

Why were tech stocks hit hard last week?

Tech stocks may have suffered from previous success — as investors rushed to sell high, looking to lock in gains as markets faltered.

Until this month, technology stocks had been among the highest-performing. They headed down amid signs of weak demand in the global economy, including falling commodities prices and dismal data out of China.

Most investors didn’t consider tech’s blue-chip stocks overvalued. The share-price-to-earnings ratio for the information technology sector at large fell only slightly to 17 from 17.26 last week, according to FactSet Research Systems Inc. data. The broader technology sector is more expensive. The P/E ratio of companies traded on the tech-laden Nasdaq exchange is 25.

But the Standard and Poor’s 500 index’s technology listings fell more than any other sector except energy last week, with Apple Inc., Google Inc. and Microsoft Corp., the top rung of U.S. tech companies, collectively losing almost $94 billion in market value.

Will tech stocks continue to fall?

They might. Technology companies already are riskier bets because many of them are valued on their potential more than today’s profits or dividends.

Investors cutting back is a sign that economic conditions have shifted enough for them to lose confidence in companies’ prospects. Many will choose to invest in safer bets such as utilities and makers of bread-and-butter consumer items, including food, beverages and household goods producers.

If those investors do go into tech, they might focus only on companies such as action camera maker GoPro Corp. and active wearable-tech firm Fitbit Co. that are growing fast on the backs of U.S. consumers — where demand remains strong.

Still, any downturn presents opportunity: Companies such as Twitter Inc., for instance, are now cheaper to buy. A subset of investors who believe strongly in certain businesses might be willing to buy their shares at the more attractive prices, said Kathleen Smith, a principal at investment advisor Renaissance Capital. If enough people fall into this category, the rebound could be swift.

Should start-ups fear going public?

Technology start-ups have tapped a seemingly bottomless reservoir of cash over the last four years, enabling many to stay private much longer than comparable companies did in previous years. That’s pushed tech IPOs to historically low levels, said Smith, who manages Renaissance’s IPO exchange-traded fund.

The 16 tech companies that went public this year represent 12% of all IPOs over the period, down from a norm of 20% to 25%, Smith said. Before last week’s slide, venture capitalists, though, described the situation as a calm before a storm.

A long-term slowdown would throw the expected downpour off course. Tech companies that went public this year have on average been underperformers, littering the market with “dead bodies,” as Smith put it.

With investor appetite even weaker now, it’s easy to see tech companies delaying IPOs as long as they can until the market improves, financial experts said. Otherwise, companies should expect to raise less cash and accept lower share prices.

Companies without huge revenue growth, positive cash flows and uncertain profitability are in the worst shape, experts said.

Would start-ups do better selling themselves?

Not necessarily. The same thinking goes for start-ups looking to be bought out. Far more start-ups are acquired or merge than go public. Large companies that have balked at many acquisitions because of high asking prices could come calling again with low-ball offers.

“You’re going to have to bear through it or sell at a discount,” said Mark Mullen of Los Angeles venture-capital firm Double M Partners. “Companies set to sell this year or next year are in trouble” if the market correction drags on.

The good news is that many start-ups have been preparing for that scenario, he said. Mullen, whose firm has invested in mobile gaming company Scopely and marketing software maker Retention Science, said he’s been telling portfolio companies to raise enough money to take them into 2017.

If young companies normally raise funds four months before expecting to run dry, they now should give themselves an eight-month window, he said.

Venture capitalists still have huge cash piles — raising more money for their funds in the second quarter than in any quarter since the start of the Great Recession. So they have the resources to prop up promising companies that need to delay IPOs.

Ernst & Young consultant Joseph Muscat said chief financial officers at large start-ups have been telling him that they “still believe in the foundations of their businesses, and they think there’s still good financing opportunities available.”

“Even in periods of volatility, with venture capitalists, private equity folks, there’s still a lot of capital pursuing private companies,” said Muscat, Ernst & Young’s strategic growth markets leader in Silicon Valley.

What happens to budding entrepreneurs in an extended slowdown?

First investors in start-ups are similar to Wall Street investors, Mullen said.

If the market is down 10%, the wealthy individuals who typically fund start-ups probably lost a similar amount of their own net worth, he said. So just like public-market investors, they will take the riskiest bets off the table first. Topping that list would be speculative investments in start-ups.

“If this is a longer-term correction, you’re going to see less capital,” Mullen said. “The appetite for new investment vehicles would go sideways.”

Even if the market contraction isn’t prolonged, the prospect of the Federal Reserve raising its benchmark interest rate this fall could be troublesome for start-ups that do manage to get slightly further along.

Investors see start-ups as one of the few paths to high returns in a market where bond and equity yields are weak. Higher interest rates would restore the safer option of investing in those markets instead of taking high-risk, high-reward stakes in start-ups.

What indicators should tech companies watch as signals of the markets’ direction?

The indicators will be the same as they are for the broader market: how investors of public companies react to consumer confidence, new home sales, manufacturing activity and other economic data, along with what the Fed decides to do next month with its federal funds rate.

Another cue would be whether venture capitalists publicly remain bullish about innovative business models.

Smith of Renaissance Capital said one test could be what happens to data storage technology start-up Pure Storage, which filed for an IPO this month and was valued at $3 billion in its most recent private financing.

“Any company similar to Pure Storage has traded down since the company filed,” she said.

So Pure Storage’s valuation theoretically should be ratcheted down. If that happens, and the economic signals remain poor, she said, expect the same for a long list of companies both public and private.

Twitter: @peard33

Times researcher Scott Wilson contributed to this report.

ALSO:

Will drone racing fly as a sport?

She brings Latin music’s top acts to the stage

How Edison uses water to store excess power

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.