New tax-inversion rules kill proposed Allergan-Pfizer merger

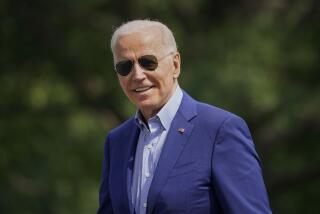

President Obama speaks Tuesday about new rules aimed at deterring tax inversions.

Reporting from Washington — The $150-billion proposed merger of Pfizer Inc. and Ireland-based Allergan has been scrapped, becoming the first casualty of an Obama administration crackdown on companies that avoid U.S. taxes by moving their headquarters overseas.

In issuing two new broad rules late Monday to deter so-called corporate inversions — the strongest such action to date — the Treasury Department seemed to be targeting the Pfizer-Allergan deal and others like it.

One of the regulations makes tax inversions harder and potentially much less profitable for foreign companies that have been involved in multiple deals with U.S. companies over a three-year period, what Treasury officials called “serial inverters.” Allergan was bought in March of last year by Actavis, a formerly New Jersey-based firm that itself had merged in 2013 with an Ireland company.

Allergan, which was born out of a Los Angeles drugstore more than 65 years ago and became best known as the maker of Botox, was expected to complete its merger with New York-based Pfizer in the second half of this year.

But Wall Street signaled that the new rules put the deal in peril. Allergan’s stock plunged 15.6% to $234.35 a share in afternoon trading Tuesday in New York. Pfizer’s stock rose 84 cents to $31.56 a share.

On Wednesday morning, Pfizer announced the deal had been called off by the two companies by “mutual agreement.”

“The decision was driven by the actions announced by the U.S. Department of Treasury on April 4, 2016, which the companies concluded qualified as an “Adverse Tax Law Change” under the merger agreement,” Pfizer said in a written statement.

Pfizer said it agreed to reimburse Allergan $150 million for expenses related to the deal, as required in the merger agreement.

“While we were surprised that the Treasury issued the rules and proposed regulations on Monday we were prepared for that contingency,” Allergan Chief Executive Brent Saunders told analysts on a conference call Wednesday.

Allergan’s future remains “incredibly exciting,” with a promising pipeline of new drugs along with a strong balance sheet and growth opportunities, he said.

“We are recharged, excited and ready to go,” Saunders said.

Allergan’s stock bounced back Wednesday, rising about 3% in early trading. Pfizer shares also were up about 3%.

But Saunders also complained that Treasury had targeted the Pfizer-Allergan deal with its new rules.

“It really looked like they did a very fine job of constructing a rule here — a temporary rule — to stop this deal, and obviously it was successful,” he told CNBC-TV.

“For the rules to be changed after the game has started to be played is a bit un-American, but that’s the situation we’re in,” Saunders said.

The new federal rules on inversions, which would apply to deals not yet closed, are the third round of efforts by the Obama White House to deter companies from leaving for tax advantages abroad. The prior actions, however, were seen as largely ineffective and drew criticisms on the political campaign trail, where the issue has been a hot topic.

MORE: Get our best stories in your Facebook feed >>

President Obama, who two years ago promised to crack down on tax inversions, said Tuesday that the new regulations “build on steps that we’ve already taken to make the system fairer.” Obama has previously chastised corporations that exploit the tax system by generally buying small companies and then changing their address to another country to reduce their U.S. tax burden. While saying that the new rules would help curb the practice, the president called on Congress to close the loophole for good by reforming the tax system.

“Let’s stop rewarding companies that are shipping jobs overseas and profit overseas,” he said, “and start rewarding companies that create jobs right here at home and are good corporate citizens.”

The Treasury Department’s new rules surprised analysts in their breadth and potential for wide impact. The second of the two main regulations focuses on blocking a tactic known as “earnings stripping,” a practice that is not limited to corporate inversions. It involves a company lending money between a U.S. and foreign affiliate so that interest payments can be deducted from U.S. tax bills.

Analysts said the new rulings are substantial expansions to the Treasury Department’s administrative actions to clamp down on a practice that has been condemned by candidates of both parties and by many members of Congress. Still, Treasury Secretary Jacob J. Lew said in a statement that although the new rules should help slow the pace of such deals, “we know companies will continue to seek new and creative ways to relocate their tax residence to avoid paying taxes here at home.”

Companies and business groups have blamed the rise in tax inversions on the high U.S. corporate tax rates that they say give foreign companies a competitive edge. But also fundamental to the debate, analysts say, are questions about what constitutes an “American” company at a time when business and capital is global, said Adam Rosenzweig, a law professor and expert in international taxes at Washington University School of Law in St. Louis.

Is corporate domicile determined by where the company is legally incorporated, where most of the employees are located, or where principal research or operations take place, he asked.

“These are positive rules, and they may stem the flow for a very short period of time,” said Kenneth Serwin, an economist and consultant with the Berkeley Research Group in Emeryville. But, he added, “this is really a big ugly Band-Aid on the problem.”

With the latest rules, analysts said the fate of the Allergan-Pfizer deal hinged on the expected nontax benefits of the merger. As of late last year, Allergan had more than 2,000 employees in Irvine, where it was long based, as well as 300 in Corona.

For one critic of the merger, David Balto, an antitrust lawyer and former policy director at the Federal Trade Commission, the inversion rules only provided more reason to oppose the transaction.

“This is a headache that’s well deserved,” said Balto, who contends the deal would have helped drive up consumers’ drug prices as competition declined. “The tax-inversion situation just made things fundamentally worse” because it meant “the American taxpayers are subsidizing the pharmaceutical industry throughout the world,” he said.

Staff writers James F. Peltz in Los Angeles and Jim Puzzanghera in Washington contributed to this report.

ALSO

Why Disney could have to go outside the Mouse House for a new CEO

Disney shares dip as Iger succession plan is thrown into question

Column: Tesla brought down by ‘hubris’? Who could have expected that?

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.