Rocket Lab launch in New Zealand brings quick, cheap space access

Cheap, quick access to space has officially arrived — and in some serious style.

Late Sunday afternoon in New Zealand, Rocket Lab successfully launched its third rocket. Dozens of employees gathered at the company’s Auckland mission control center clad in Rocket Lab’s black-and-red colors and let out a series of primordial screams as the rocket took off, flew into space and dropped its satellite payload into orbit.

Although issues had delayed this launch for months, Sunday’s event went off without a hitch. Rocket Lab — headquartered in Huntington Beach — has now established itself in the lead position of a frenetic, worldwide competition to change the economics and speed at which people can get things into space.

“It’s game on,” said Peter Beck, the company’s founder and chief executive, in an interview outside of Rocket Lab’s mission control in Auckland. “This era has been coming and coming. Well, the small launch race is over. We have proven it can be done.”

The rocket dubbed It’s Business Time — after a song by the New Zealand comedy duo Flight of the Conchords — took off just before 5 p.m. local time from a spaceport in New Zealand.

It carried six satellites into low Earth orbit. Two of them belonged to the start-up Spire and will be used to track ships, planes and weather in remote parts of the world, while Tyvak Nano-Satellite System also put up a weather satellite. Another was built by students at six high schools in Irvine and will be used to gather data around the satellite’s performance and used as a teaching aid.

And, in a show of Down Under harmony, the Australian start-up Fleet Space Technologies sent up two satellites that will be used as the foundation for a new telecommunications network. Fleet has spent all year waiting to hitch rides on rockets from SpaceX and the Indian government, and has been plagued by delays.

About six weeks ago, it found out there was room on the Rocket Lab rocket. Typically, it takes months or years to get satellites ready, installed and certified for launch, but in this new era of cheap, fast space flight, Fleet got its hardware on board in record time.

“I don’t think anyone thought this was possible,” said Flavia Tata Nardini, co-founder and CEO of Fleet. “I can’t believe we actually did it.”

For decades, the main path to space has run through a handful of large, government-backed organizations that charged $150 million to $300 million per flight. Their massive rockets were lucky to fly once a month and typically carried bus-sized satellites.

Elon Musk’s SpaceX caused a massive upheaval in this market by showing that a private space company could launch large rockets at a fraction of the cost — $60 million per flight — and do so much more often.

Rocket Lab represents a second dramatic shift in the launch industry toward smaller, cheaper rockets that fly almost every day. It makes a 56-foot tall rocket (Electron) versus SpaceX’s 230-foot tall rocket (Falcon 9) and charges $5.7 million per launch. SpaceX can take far more cargo to space, but Rocket Lab is pitching its nimbleness and low cost as ways to give new customers access to space and to do so on a more convenient schedule.

Dozens of satellite start-ups have appeared over the past two years, hoping to take advantage of these small rockets. They’re making shoebox-sized satellites for imaging, science missions and communications.

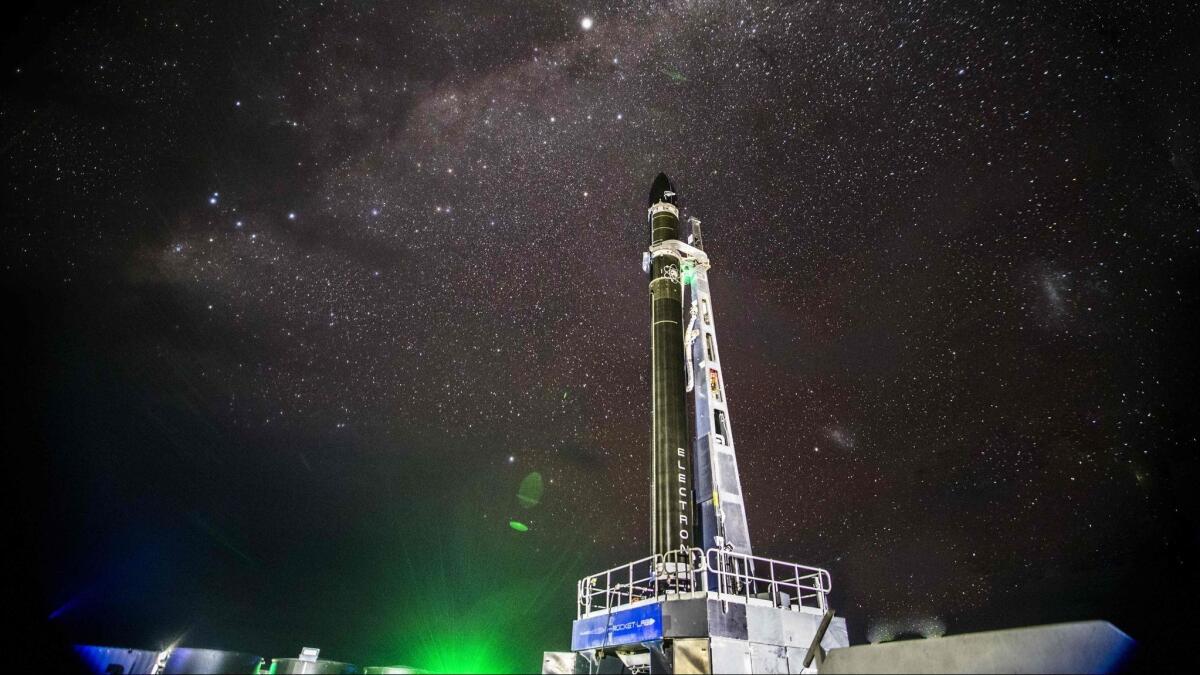

Sunday’s launch took place at Rocket Lab’s private spaceport located on a sheep farm in the Māhia Peninsula on the far eastern edge of New Zealand’s North Island.

Private spaceports are a rarity, and Rocket Lab’s is the only one that is seeing regular use. Its remote location should allow Rocket Lab to launch frequently — the company hopes to get to one launch a week and then to one every three days — as air and boat traffic are relatively low. This launch, however, did have to take the path of the Majestic Princess, one of the world’s biggest cruise ships, into account as it was scheduled to briefly pass by the launchpad.

Rocket Lab recently moved into a new facility in Auckland, where it has both mission control and a factory for producing rockets. The entry to the building has a futuristic feel with its minimal lighting, black walls and red glowing accents along the walls — all of which leads to the glass-enclosed mission control. Deep inside the factory, workers have a handful of rockets at various stages of assembly, awaiting their turn to be thrust into space.

To date, Rocket Lab has raised $148 million from investors betting that it could end up as the FedEx of space. Dozens of other companies around the world are scrambling to build small rockets of their own, including Firefly Aerospace, Virgin Orbit and Vector Launch Inc.

Rocket Lab, however, now has a clear edge in the race to cheap space with most of the other companies still in the prototyping and testing stage of their operations. Rocket Lab already has plans to conduct another launch in December and recently broke ground at a second launch site in the U.S. to support even more launches.

The company’s first successful test launch took place in May 2017, and in January 2018, it sent a second rocket into space with a handful of customers’ satellites. Both of the flights were considered tests of Rocket Lab’s technology with this third flight being the moment when business would kick off in earnest.

Rocket Lab, though, faced two false starts trying to get its third rocket to launch. The biggest issue hampering the launches revolved around a motor controller with a flawed design that triggered errors ahead of liftoff. Rocket Lab’s engineers have since redesigned the part. Even though the company lost some momentum, the delay did give it time to regroup at the production facility and to line up more rockets for a quick succession of launches.

The company was started by Beck, a largely self-taught engineer, who had dreamed of building rockets since his childhood growing up on New Zealand’s South Island. Beck and a handful of engineers guided Rocket Lab through the first few years of the company’s existence, building smaller prototype rockets.

Once the technology started to take shape, Beck was able to bring in outside investors to scale up the operation and also to help the New Zealand government create an aerospace industry out of thin air.

“It’s just an awesome accomplishment from the team and a textbook launch,” Beck said.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.