PG&E files for bankruptcy protection. Here’s why that could mean bigger electricity bills

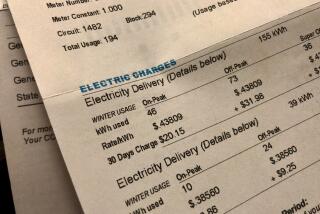

PG&E Corp., which owns California’s largest electric utility, filed for bankruptcy protection Tuesday in anticipation of huge legal claims, starting an unpredictable process that could take years to resolve and is likely to result in higher energy bills for the millions of Californians who depend on Pacific Gas & Electric for power.

PG&E said a Chapter 11 bankruptcy filing, which allows the company to continue operating while it comes up with a plan to pay its debts, was the only way to deal with billions of dollars in potential liabilities from a series of deadly wildfires, many of which were sparked by the company’s power grid infrastructure.

“Through this process, we will prioritize what matters most to our customers and the communities we serve — safety and reliability,” interim Chief Executive John R. Simon said in a statement. “We believe that this process will make sure that we have sufficient liquidity to serve our customers and support our operations and obligations.”

Energy experts say PG&E’s rates probably will increase when the utility emerges from Chapter 11 protection because bankruptcy inevitably makes it more expensive for a company to borrow money and creates large legal and other bankruptcy-related costs. The utility passes such expenses along to its customers.

“It’s almost impossible to see a way out of this that doesn’t have some short-term cost increases,” Ralph Cavanagh, co-director of the energy program at the Natural Resources Defense Council, said in a recent interview.

A bankruptcy judge could also allow PG&E to reduce its eventual payouts to California fire victims. That could include Paradise residents whose homes were destroyed by last year’s Camp fire, if PG&E’s equipment is found to have sparked the blaze. The utility has already started skipping payments to families whose properties were destroyed by the 2015 Butte fire, which was caused by a tree falling on a PG&E power line.

PG&E officials say electricity and natural gas service will continue uninterrupted for its 16 million customers in Northern and Central California. The company has lined up at least $5.5 billion from several banks to fund its operations during what it expects to be a two-year bankruptcy process, and it filed a motion Tuesday asking the court to approve that so-called debtor-in-possession agreement.

PG&E’s bankruptcy could slow California’s fight against climate change »

Lawmakers watched in dismay as PG&E chose bankruptcy, but there was nothing they could do to stop the company from filing. State Sen. Bill Dodd (D-Napa) said the situation is “extremely disappointing and underscores the need for change at PG&E in both its leadership and corporate culture.” Assemblyman Chris Holden (D-Pasadena), who chairs the Utilities and Energy Committee, lamented that the effect on fire victims and PG&E ratepayers “may be severe.”

“Our goal all along was to protect the most vulnerable, but now the Bankruptcy Court will be managing the future of PG&E and its creditors, including the damages of fire victims for which the utility is deemed responsible,” Holden said in a statement.

PG&E listed $71.4 billion in assets and nearly $51.7 billion in total debts. The firm said it filed requests for authorization to continue paying employee wages and to continue existing customer programs, including energy efficiency and support for low-income ratepayers. It also said it intends to pay its suppliers under normal terms for goods and services provided on or after the date of the bankruptcy filing.

Financial pressure has been mounting on PG&E since October 2017, when a series of wildfires ravaged Northern California, killing 44 people. State investigators determined that PG&E’s equipment sparked or contributed to more than a dozen of those fires, which killed 22 people. The company’s crisis only grew with the November 2018 Camp fire, which killed 86 people and destroyed most of the town of Paradise.

The California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection has yet to announce a cause for the Camp fire, but PG&E’s infrastructure is suspected. The utility company’s stock has lost more than 80% of its value since the 2017 fires broke out, and its credit rating has been downgraded to junk status.

PG&E has blamed its wildfire costs, in part, on climate change, which scientists say is contributing to bigger and hotter fires in California and across the western United States. The company has also pushed lawmakers to rewrite the state’s strict liability laws, which allow utilities to be held liable for wildfires sparked by their infrastructure even if they follow all safety rules and aren’t found negligent.

PG&E has estimated its potential wildfire liabilities at $30 billion or more, although that number includes the Tubbs fire, the biggest and deadliest of the 2017 Northern California blazes. Cal Fire announced last week that the Tubbs fire wasn’t caused by PG&E, which by some estimates could cut the company’s potential liabilities in half.

Even without Tubbs fire damages on its ledger, PG&E’s liabilities could still exceed the company’s market value, which was down to about $7 billion on Tuesday.

“To be clear, we have heard the calls for change and we are determined to take action throughout this process to build the energy system our customers want and deserve,” Simon, the company’s chief executive, said Tuesday.

Critics say PG&E has exaggerated its financial woes and is filing for bankruptcy as a ploy to extract investor-friendly concessions from the Legislature or regulators. Those critics include ratepayer advocacy groups and lawyers for fire victims, whose clients could see court awards reduced by a bankruptcy judge. They also include BlueMountain Capital Management, a hedge fund that holds more than 11 million shares of PG&E stock that could be wiped out.

BlueMountain urged PG&E’s management not to go through with the bankruptcy filing and said last week it would nominate a full slate of new directors to the company’s board.

“Instead of rolling up their sleeves and getting to work, current board members are poised to concede defeat and pass the buck to a bankruptcy judge. There is no imminent financial crisis — there is a leadership crisis,” BlueMountain said in an open letter to other shareholders, asking them to join the hedge fund in its protests.

Here’s how local governments are replacing California’s biggest utilities »

In addition to the likelihood of higher electricity rates and lower payouts for wildfire victims, PG&E’s bankruptcy could affect California’s ability to meet its climate change goals. Those goals depend on a rapid transition from fossil fuels to climate-friendly power sources, and state officials have been counting on PG&E to make massive investments in solar and wind farms and other clean energy technologies.

Already, PG&E has suggested it could seek to nullify existing contracts to buy power from solar and wind farms, or to slash payments under those deals. That possibility is worrying developers who have contracts with PG&E, and clean energy advocates who fear a chain reaction where lenders are hesitant to finance future projects in California.

The Florida-based developer NextEra Energy Resources has asked the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission to protect its contracts with PG&E. The agency gave NextEra an early victory last week, ruling it has “concurrent jurisdiction” with the bankruptcy court over those contracts. But PG&E objected on Tuesday, asking the bankruptcy court to declare that federal regulators have no say over the fate of those contracts.

The bankruptcy filing could also hurt the state’s plans to promote electric vehicles, a critical component of efforts to reduce planet-warming carbon dioxide emissions. Officials are counting on PG&E and other big utilities to spend billions of dollars in the coming years building electric vehicle chargers and preparing the power grid for a big boost in electricity demand from car charging.

PG&E’s bankruptcy “makes that even much more difficult to achieve,” said Mary Nichols, the powerful regulator who leads the California Air Resources Board.

Still, it’s far from clear what will happen next.

Some PG&E critics have called for the Legislature and Gov. Gavin Newsom to break the company into smaller pieces or convert it into a public entity. San Francisco has said it will study the possibility of acquiring PG&E’s electrical infrastructure in the city.

Most utility experts say a government takeover is unlikely because it could saddle state or local agencies with huge liabilities from future fires, without addressing the causes of those fires. Newsom has played his cards close to his vest, saying Tuesday that his administration “will continue working to ensure that Californians have access to safe, reliable and affordable service, that victims and employees are treated fairly, and that California continues to make forward progress on our climate change goals.”

PG&E’s bankruptcy filing “does not change my focus, which remains protecting the best interests of the people of California,” Newsom said in a statement.

Unlike most companies that enter into bankruptcy protection, PG&E is a regulated monopoly that provides an essential public service. The California Public Utilities Commission will need to approve any reorganization plan that involves raising electricity rates, giving the state some ability to protect the interests of ratepayers.

But critics aren’t happy with how the commission and its president, Michael Picker, have handled PG&E’s bankruptcy so far.

On Monday, the commission unanimously approved the company’s request to take on up to $10 billion in emergency financing, over the objections of consumer watchdog groups that said the agency was needlessly rushing to accommodate PG&E’s planned Chapter 11 filing. The raucous meeting, held on short notice, was attended by angry utility customers and labor representatives who chanted “shame, shame” as the commissioners voted.

The commission’s own Public Advocates Office said the agency’s decision failed to include important safeguards for ratepayers, such as requiring that none of the financing go toward management bonuses or to any other purpose not necessary to keep the lights on. The Utility Reform Network, an independent ratepayer advocacy group based in San Francisco, accused the commission of blindly accepting PG&E’s claim that it needed billions in emergency cash to fund its operations.

Picker defended the commission’s decision on Monday, citing a “substantial risk” that PG&E won’t be able to keep providing reliable power and gas service without the emergency funding. He also said PG&E won’t be able to pass along any of the costs to ratepayers until the commission reviews how the utility ultimately spends the money.

“The action does not encourage or enable PG&E to seek bankruptcy. Under federal law that is their choice. This decision just ensures they can take actions necessary to continue providing service in bankruptcy,” Picker said.

Even without the fires, PG&E continues to grapple with the fallout from the 2010 explosion of one of its natural gas pipelines, which killed eight people and destroyed 38 homes in San Bruno. PG&E was fined $1.6 billion by the PUC and $3 million by a federal judge. Just last month, the commission accused PG&E of falsifying pipeline safety records for years after the deadly explosion.

The company is still on probation after a criminal conviction stemming from the gas explosion. The federal judge overseeing the probation, William Alsup, said this month that he may order PG&E to inspect its entire electric grid and do extensive tree-trimming before this summer, which PG&E says could cost as much as $150 billion.

Alsup also suggested he could order PG&E to preemptively shut off electricity in certain areas when strong wind and other weather conditions create a high fire risk. PG&E and the state’s other big investor-owned utilities, Southern California Edison and San Diego Gas & Electric, rarely use preemptive power shutoffs as a wildfire prevention strategy, but that could change as climate change fuels bigger fires.

The last time PG&E filed for bankruptcy, in 2001, fires had nothing to do with it.

That bankruptcy was a result of California’s infamous energy crisis, in which a failed deregulation plan allowed Enron Corp. and other energy traders to manipulate markets and send prices skyrocketing. PG&E said it needed relief from $9 billion in debt that it incurred because it couldn’t recover its higher costs from ratepayers.

PG&E emerged from that bankruptcy process with a reorganization plan that saw investors largely made whole. The company was also allowed to boost its regulated profits for years to come. Customers, meanwhile, were saddled with higher rates.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.