Column: The conflict between Apple and the FBI has a long history--and your privacy is at stake

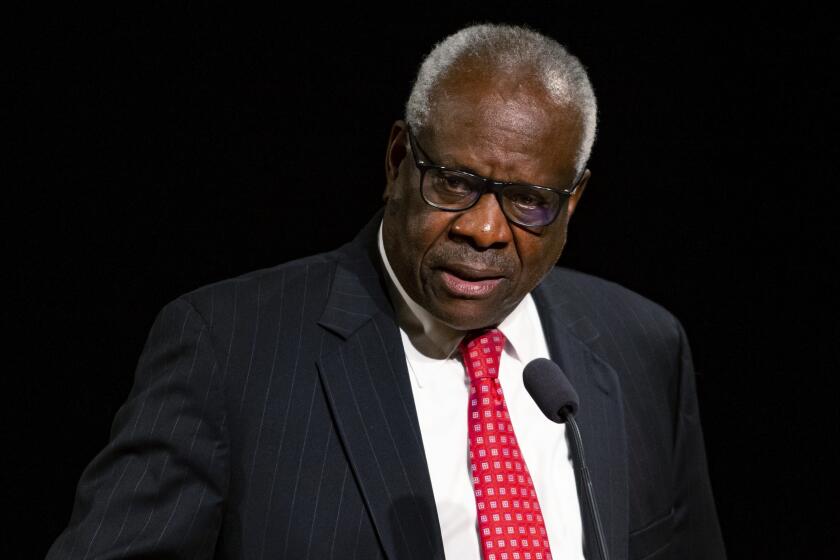

Apple CEO Tim Cook.

The consumer technology industry and the law enforcement community have been on a collision course over consumer privacy for years. Now, in the confrontation between Apple and the FBI over unlocking the iPhone of one of the San Bernardino attackers, that collision finally has happened.

The details of the case are by now well known. Acting on a motion by the FBI, U.S. Magistrate Sheri Pym of Riverside ordered Apple to help the FBI break into the iPhone used by Syed Rizwan Farook, one of the perpetrators of the San Bernardino terrorist attack on Dec. 2, which left 14 people dead. The FBI says it has been unable to bypass the phone’s password protection of Farook’s iPhone because he’s assumed to have taken advantage of device settings designed to thwart such unauthorized access.

The case raises the intertwined issues of how far manufacturers should go in protecting their customers from privacy invasions, and how far government authorities should go in gaining access to people’s private data.

These are not new issues. “This is part of a battle over strong encryption and law-enforcement access that goes back 25 years,” Marc Rotenberg, executive director of the Electronic Privacy Information Center, or EPIC, told me. “I had hoped that the government had reached the conclusion that it was better to encourage strong encryption to protect American consumers and American businesses than to go down the path of broken encryption.”

The harvest of our failure to install strong encryption in consumer and business systems, he says, is the repeated occurrence of data breaches that compromise people’s personal data. “It’s really quite dangerous and we’re paying an enormous price for it.”

American consumers are becoming more sensitive to the potential for technological invasions of their privacy. Revelations of government spying on phone conversations, made by whistleblowers such as Edward Snowden, and of prosecutors’ overreaching have sharpened the tech community’s sense that weakened security threatens the privacy of the average citizen more than it aids law-enforcement—and also sharpened suspicions of government motivations.

“How much of the data the FBI wants [in the San Bernardino case] is really on the phone, and how much of this is really about the FBI just wanting into the phone?” asks David Auerbach, a software expert at the think tank New America and frequent contributor to Slate.com.

The FBI and federal prosecutors argue that allowing wrongdoers to conceal their intentions or evade detection by hiding behind strong encryption is a threat to the public. At one fraught 2014 meeting with Apple executives, a high-ranking federal prosecutor reportedly predicted that the day would come that a child would die because police couldn’t penetrate the security on a killer’s phone.

In the San Bernardino case, the government argued in a motion Friday that Apple’s assistance in helping the FBI crack Farook’s password should be compelled because of “the urgency of this investigation.” Yet assertions that constitutional and legal protections for individual privacy give aid chiefly to criminals or traitors have been common over the decades, as when Abraham Lincoln suspended the writ of habeas corpus during the Civil War. But such erosions of civil rights often have been regarded with remorse in retrospect.

Apple and its defenders are right to doubt the FBI’s assertions that the San Bernardino case represents a one-time-only request mandated by the exigencies of a terrorism investigation. History tells us that once granted an investigative tool, law enforcement is reluctant to give it up. Apple CEO Tim Cook made that point in his public statement about the assistance the FBI is seeking, published on Apple’s website: “While the government may argue that its use would be limited to this case, there is no way to guarantee such control.”

It’s hard to avoid the conclusion that in recent years, Americans’ privacy has become immeasurably less secure, and that has made us anything but safer. The list of data breaches affecting ordinary consumers and employees revealed in 2015 alone is stunning. They include the theft of data from personnel records of 21.5 million federal workers, including fingerprints of 5.6 million workers, on file with the government’s office of Personnel Management; the exposure of personal data of 80 million persons held by the health insurer Anthem; and records of 330,000 taxpayers vacuumed up from the Internal Revenue Service and used to collect bogus refunds.

That’s on top of such publicity-garnering hacks as the 2014 invasion of computers at Sony Pictures, which forced the company to shut down its computer systems and resulted in the release of thousands of compromising and embarrassing emails, among other data.

Apple has taken an increasingly firm stand on user privacy, banking its reputation not merely on its elegant hardware but on its image as a champion of customer privacy. In opposing an order similar to Pym’s in a New York case last year, the company asserted that “public sensitivity to issues regarding digital privacy and security is at an unprecedented level,” including “in the area of government access—both disclosed and covert.” It stated that it has “taken a leadership role in the protection of its customers’ personal data against any form of improper access.” Helping prosecutors break a defendant’s password, it said then, could “substantially tarnish the Apple brand.”

In a statement published on the company’s website, CEO Tim Cook has vowed to challenge Pym’s order, which he labeled “an unprecedented step which threatens the security of our customers.” (The company’s formal response is due in court by the end of this week.) Cook went further in a speech last June upon accepting EPIC’s 2015 Champions of Freedom Award: Weakening encryption, he said then, “has a chilling effect on our First Amendment rights and undermines our country’s founding principles.”

On the other side of the argument is FBI Director James Comey, who has been campaigning to require tech companies to provide law enforcement with “back doors” allowing authorities to penetrate even the strongest consumer privacy protections. Comey complained as early as 2014 about the strong encryption being installed in the newest generation of consumer devices. “We have the legal authority to intercept and access communications and information pursuant to court order,” he said, “but we often lack the technical ability to do so.”

That appears to be true of Farook’s iPhone, which the FBI has been unable to crack to obtain data from the last weeks before he and his wife, Tashfeen Malik, staged the massacre. They died in the aftermath. Among the material locked away could be messages, emails, photos, contacts, call records and travel routes the FBI says could be crucial to its investigation of the attack.

Apple plainly knew it was heading toward a confrontation with the government, and tried to inoculate itself by reducing its own ability to break its users’ privacy and giving them more power to control their own passwords. Its iOS 9 operating system is what gave Farook the ability to block password-breaking efforts. The company may simply not have gone far enough to take itself out of the loop; although Apple has hinted in at least one previous case that the access sought by the government is technically unfeasible, there are other indications that the company could meet the magistrate’s order if it wished.

In his posted statement, for instance, Cook observed that the new version of the iPhone’s operating system requested by the FBI could theoretically be created: “Once created, the technique could be used over and over again, on any number of devices....In the wrong hands, this software — which does not exist today — would have the potential to unlock any iPhone in someone’s physical possession.”

The U.S. is not the only place where Apple and other tech companies are fighting for privacy safeguards. China last December passed a law requiring companies such as Apple to provide “technical interfaces, decryption and other technical support assistance” to Chinese authorities in anti-terrorism cases. The law places Apple in a delicate position, since the company obtains some 25% of its revenue from “greater China,” which includes Hong Kong and Taiwan and is its fastest-growing market.

Chinese authorities backed away from their most stringent original proposals, including a requirement that device makers provide a “backdoor” to allow the government to decode encrypted information, but many experts predict that a confrontation between Apple and the Chinese over the law is only a matter of time.

That said, Apple’s stance against providing user information to government authorities is anything but absolute. The company accepts that data from iPhones and iPads backed up to its iCloud servers are subject to search warrants, and Apple routinely cooperates with such orders. Indeed, the FBI says it collected via a warrant “all iCloud data” associated with Farook’s iPhone up to Oct. 19, when he apparently stopped backing it up to keep subsequent data concealed. (Apple’s Cook also acknowledged that the company has complied with “valid subpoenas and search warrants...in the San Bernardino case.”)

One’s opinion about how to balance privacy and prosecution depends on how one weighs the threat to privacy against the threat from secrecy. But Cook is surely correct in maintaining that consumers want and need more protection from unauthorized snooping, not less. By challenging Magistrate Pym’s order, Apple may at least force the government to state outright where it thinks the balance should be struck, and why.

Keep up to date with Michael Hiltzik. Follow @hiltzikm on Twitter, see our Facebook page, or email [email protected].

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.