An abandoned mine near Joshua Tree could host a massive hydropower project

An abandoned iron mine on the doorstep of Joshua Tree National Park could be repurposed as a massive hydroelectric power plant under a bill with bipartisan support in the state Legislature.

Senate Bill 772, which was approved by a panel of lawmakers last week with no dissenting votes, would require California to build energy projects that can store large amounts of power for long periods of time. It’s a type of technology the state is likely to need as utility companies buy more and more energy from solar and wind farms, which generate electricity only when the sun is shining or the wind is blowing.

But SB 772 is a controversial solution to that problem. The bill could jump-start a $2.5-billion hydropower project that critics say would harm Joshua Tree National Park, draining desert groundwater aquifers and sapping above-ground springs that nourish wildlife in and around the park.

The bill is being pushed by NextEra Energy, a Florida-based company that hopes to build the proposed Eagle Mountain hydropower project.

NextEra is the world’s largest operator of solar and wind farms, with nearly $17 billion in revenue last year. The company and its affiliates have spent heavily on lobbying and showered campaign contributions on California lawmakers, giving nearly a quarter-million dollars to Senate and Assembly candidates in the most recent election cycle, campaign finance filings show.

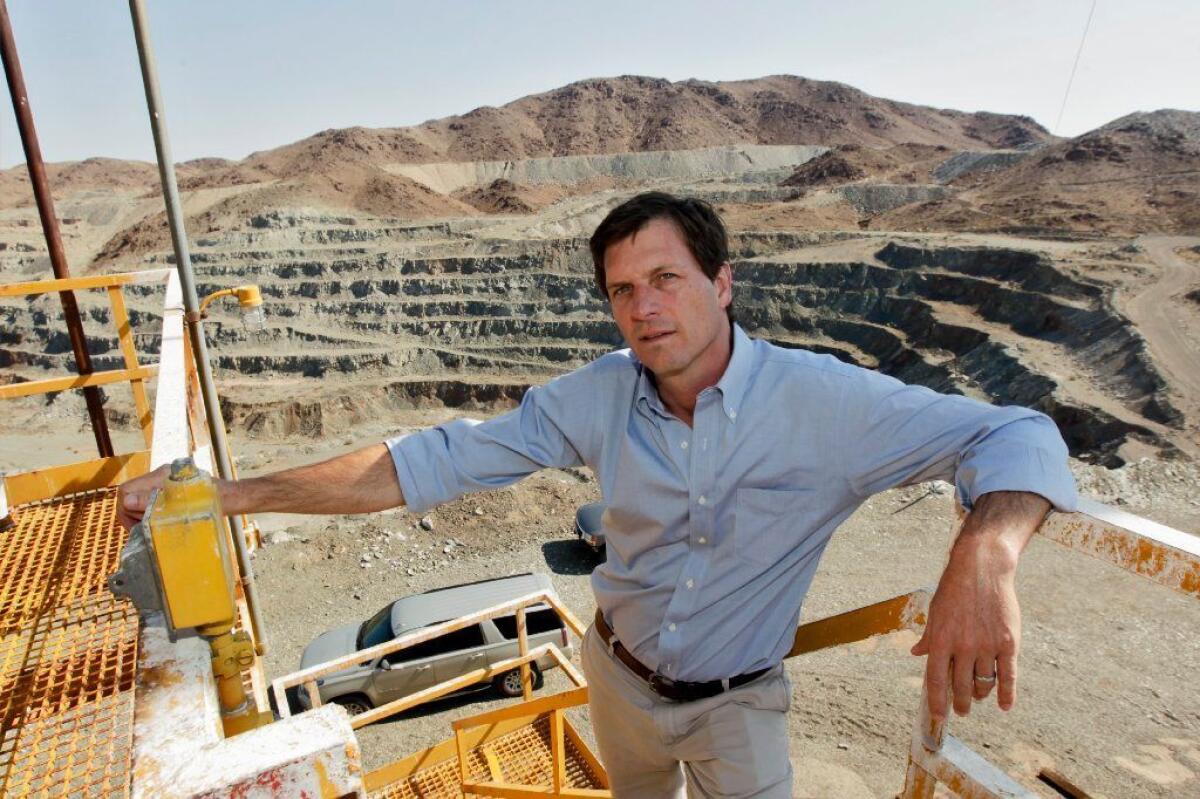

The Eagle Mountain facility would be surrounded on three sides by Joshua Tree National Park, just north of Interstate 10 in eastern Riverside County. The lands were originally part of Joshua Tree National Monument, the predecessor to the park, but were carved out for iron mining after World War II.

For years, outdoors advocates and tourism officials have campaigned for the Eagle Mountain area to be added to the national park. The lands are traversed by bighorn sheep, golden eagles and desert tortoises. There’s also a well-preserved ghost town from the area’s mining days, which conservationists say has historic value.

David Lamfrom, California desert program manager for the National Parks Conservation Assn., said energy development and conservation present “two different visions for the future” of the Eagle Mountain lands.

“One is based on extracting precious groundwater from a sensitive and already over-allocated basin,” Lamfrom said. “The other is to connect people to the beauty of the desert, and to tell the story of what life was like here.”

NextEra acquired a majority stake last year in the hydropower project’s developer, Santa Monica-based Eagle Crest Energy Co. The companies plan to pump billions of gallons of groundwater, filling an abandoned mining pit.

When cheap renewable energy floods the power grid — during the middle of the day, for instance, when the sun is shining and electricity demand is low — the companies would pump the water uphill to another mining pit, effectively storing the clean power. Then in the evening, when the sun goes down and electricity demand rises, the water would be released back downhill to the lower pit through a turbine, generating electricity.

NextEra and its allies say California will need projects like Eagle Mountain to meet its legally mandated goals of 60% renewable energy by 2030 and 100% climate-friendly energy by 2045. Supporters of SB 772 point to the shortcomings of lithium-ion batteries, which typically supply just a few hours’ worth of stored energy.

“Renewable energy is intermittent by nature. If we want to achieve our 2045 zero-carbon power goals, we need bulk energy storage to help balance the grid,” the bill’s author, Sen. Steven Bradford (D-Gardena), said last month at a meeting of the Senate’s energy and utilities committee. “We can debate exactly when we will need this resource, but by the time we act it will be probably too late. We cannot wait to fix this problem.”

A war is brewing over lithium mining at the edge of Death Valley »

Bradford received $6,500 in campaign support from NextEra over the last two years. His bill would require the California Independent System Operator, which runs the power grid for most of the state, to buy at least 2,000 megawatts worth of power from “one or more long duration energy storage projects” in the next three years.

The grid operator would charge the costs of those projects to ratepayers across the state, excluding areas served by utilities that run their own electric grids, such as the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power.

Kerry Hattevik, NextEra’s regional director of government affairs, told the state Senate energy committee last month that the bill fills a “regulatory gap” by requiring large infrastructure projects that will be necessary to meet the state’s clean energy goals, but that are larger than any one utility needs or can afford to pay for.

“California must invest in bulk energy storage now,” she said. “The soonest you’re going to see a project online is 2030. The soonest you’re going to see any project hit rates is 2030. These are 10-year construction cycles.”

SB 772 doesn’t specify that hydropower projects would need to be built.

But there don’t appear to be other technologies capable of providing the kind of energy storage the legislation requires, at least not in the next three years. And while there are a handful of pumped storage projects in the works in California, none is nearly as far along as Eagle Mountain.

“This is just NextEra trying to use California utility customers as their personal cash register,” said Barry Moline, executive director of the California Municipal Utilities Assn., some of whose members’ customers would foot the bill. “This is putting somewhere from a $3 billion to $10 billion bet on one technology, and more significantly one project and one company.”

SB 772 is NextEra’s second attempt at a bulk energy storage bill, after the failure last year of similar legislation from Assemblyman Bill Quirk (D-Hayward). This year’s version made it through the Senate energy committee on a 9-1 vote, and was advanced unanimously by the chamber’s appropriations committee last week. It would need to be approved on the Senate floor by May 31 to be considered in the Assembly this year.

The bill’s coauthors include eight Democrats and three Republicans, all of whom received campaign funds from NextEra in the last election cycle. The bill’s other supporters include at least nine organized labor groups.

Scott Wetch, an influential labor lobbyist hired by NextEra, told lawmakers that union support for SB 100 — the 100% clean energy mandate approved last year — was contingent on the promise of big infrastructure projects.

“In 2017, when SB 100 was held up in the Assembly, we were opposed,” Wetch told the Senate energy committee last month. “This singular acknowledgment that we would need this level of infrastructure to make that goal obtainable is the reason that we came in support of that bill and helped make that a reality.”

Hydropower bill would sabotage California’s clean energy mandate, critics say »

Even with union support, it’s not clear SB 772 has the votes to clear the Senate. Several lawmakers who voted for the legislation in committee said they still had serious concerns with the bill — including the appearance it was designed to support a specific project — and wouldn’t support it on the Senate floor without changes.

Some lawmakers also worried the bill could invite the federal government to interfere in California’s energy policies. The California Independent System Operator, which under the terms of SB 772 would be required to buy large amounts of energy storage for the state, is regulated by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, or FERC. Three of the five commission members are Republicans appointed by President Donald Trump.

“Our concern is that FERC wouldn’t necessary have California’s interests at heart,” said Sen. Nancy Skinner (D-Berkeley), who also complained that the bill favors pumped storage and is “not technology-neutral.”

Stephen Berberich, president of the California Independent System Operator, has raised concerns about expanding the organization’s responsibilities to include signing long-term energy contracts. He also questioned the wisdom of legislative support for pumped storage, even as he described it as “one of the best assets you can have on the system.”

“On these big asset projects, really what we’re doing is predicting the future. It’s going to take many years to get a bulk pumped storage project online,” Berberich said in an interview. “And what’s the future of storage at that point? Who’s to say that flow batteries aren’t prevalent and a lot cheaper at that point? And then you’re going to have a big asset on the system that you’re paying for for a long, long time.”

For environmental groups, SB 772 is the latest battle in a decades-long fight to protect Joshua Tree National Park from industrial development in the Eagle Mountain area.

Plans for a huge garbage dump were abandoned in 2013 when the Sanitation Districts of Los Angeles County backed out. A year later, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission issued a permit for a hydropower project — following environmental reviews that were based on aerial surveys and publicly available information because the developers didn’t have access to the site at the time.

“The branding of the Eagle Crest project as a renewable energy project doesn’t speak to whether or not this is the right place,” Lamfrom said. “The fundamental question is, does this project take away more than it gives?”

In an emailed statement, NextEra spokesman Steve Stengel said the company has “committed to ongoing mitigation and monitoring to assure the environment is protected.”

“The work we do benefits Californians and California businesses and we are proud to support sound public policy,” he said.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.