Something Trump and Elizabeth Warren agree on: Bringing back Glass-Steagall to break up big banks

Carter Glass and Thomas Steagall have been dead for more than 70 years. But the two congressmen apparently can still accomplish the seemingly impossible: unite big names in a sharply divided Washington.

The roster of those who want to break up the biggest U.S. banks by restoring a key piece of legislation Glass and Steagall sponsored in the midst of the Great Depression includes President Trump; liberal firebrand Sen. Elizabeth Warren; Trump economic advisor and former Goldman Sachs executive Gary Cohn; avowed Democratic Socialist Sen.

Glass-Steagall, as the 1933 law was known, is credited with helping keep the U.S. financial system safe from a major crash until it was largely repealed in 1999.

Within a decade, the financial system was in severe crisis.

Whether the two events were related, and whether a restoration of Glass-Steagall would prevent another collapse, is up for debate. But demands have persisted from the left and right to bring back Glass-Steagall provisions that effectively separated commercial banking from riskier investment banking. The Republican Party’s official 2016 platform called for it. So did the 2016 Democratic Party platform.

“There are, you know, some people that want to go back to the old system, right?” Trump said when asked about the issue in a recent interview by Bloomberg News. “We’re looking at it right now as we speak.”

Cohn has indicated he supports restoring Glass-Steagall, but the Trump administration probably would want to accompany such a move with a reduction in other financial regulations.

Last month, Warren (D-Mass.) joined with McCain (R-Ariz.) to introduce legislation to restore Glass-Steagall’s prohibition on banks with federally insured deposits from selling investments and insurance.

Sanders is among the bill’s backers. Lee (D-Oakland) is among 47 co-sponsors of similar legislation in the House.

The bills, opposed by big banks, would force large institutions such as Citigroup Inc.,

“Despite the progress since 2008, the biggest banks continue to threaten our economy,” Warren said in introducing the bill. “Reinstating Glass-Steagall has broad bipartisan support, and it’s time to get it done.”

Here’s a look at what such a move would — and wouldn’t — accomplish.

‘A prolific source of evil’

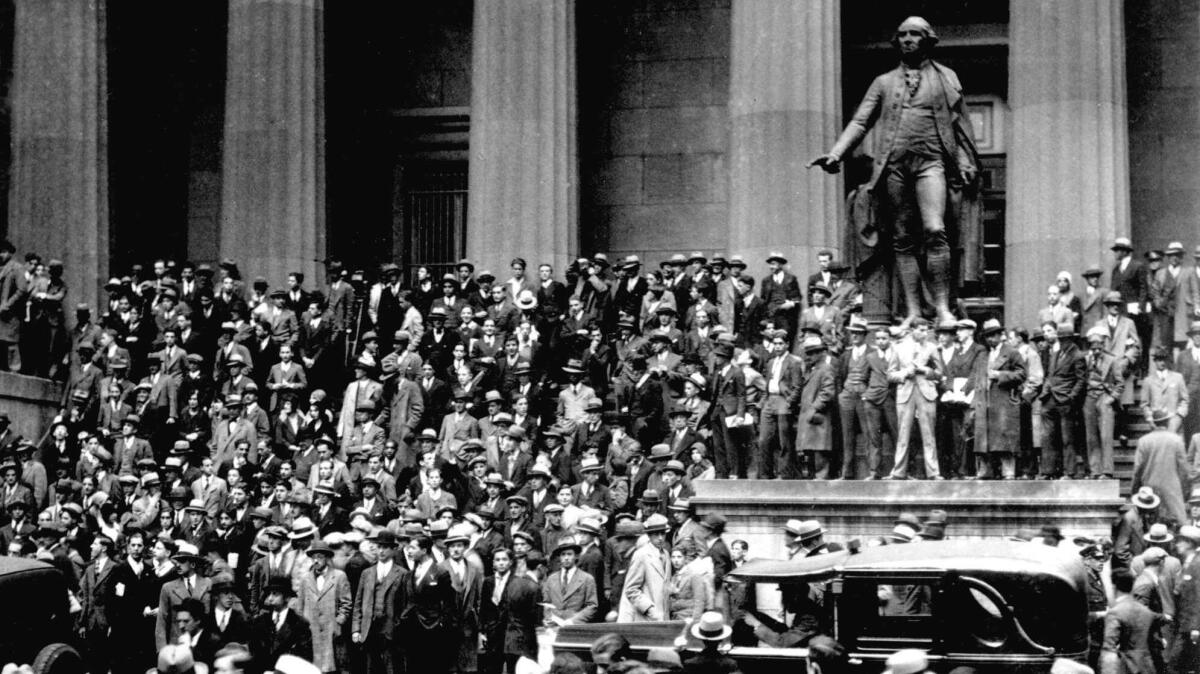

With World War I over and the economy booming in the 1920s, Americans poured money into the stock market. The Dow Jones industrial average more than quadrupled from 1924 to 1929.

Then in October 1929, the Roaring ’20s came to a resounding end.

Stock prices began plummeting. The Dow dropped 13% on Oct. 28, what would be called Black Monday. It dropped another 13% the following day, Black Tuesday. And it kept falling.

The stock market crash helped trigger the Great Depression, the worst financial crisis and economic downturn in U.S. history.

The

Commercial banking involves taking deposits and making loans. Investment banking is all about selling stocks and other securities. Investigators believed commercial banks had fueled the rampant stock speculation leading up to the crash.

“A prolific source of evil has been the affiliated investment companies of large commercial banks,” the report said. Commercial banks referred customers to affiliates that “unloaded securities owned by them on unsuspecting investors and depositors,” the commission found.

Congress already was working on a solution.

A banking wall goes up

What now is known as Glass-Steagall was just part of the Banking Act of 1933, which included the creation of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. and other reforms to safeguard the financial system. The act also aimed to “prevent the undue diversion of funds into speculative operations.”

Four provisions had the effect of separating deposit-taking — which now was federally insured — and investment banking:

- Banks were prohibited from underwriting and dealing in securities (with the exception of government-issued bonds);

- Banks were not allowed to be affiliated with any businesses that were “principally engaged” in securities activities;

- Securities firms and other nonbanks were not allowed to take deposits;

- Banks and securities firms could not share directors or managers.

As an example of the law’s effect, the J.P. Morgan banking empire was forced to split up. J.P. Morgan & Co. became a commercial bank while the investment business was spun off into a separate company called Morgan Stanley.

Soon, though, a growing industry chafed at the restrictions.

‘The Shatterer of Glass-Steagall’

It didn’t take long for banks to find loopholes and lobby for changes.

New classes of securities were added to the exemptions in the law. Investment banks began offering money-market accounts that acted like bank accounts. And the

The final straw came in 1998. Amid a wave of industry consolidation, Citicorp, which owned Citibank, agreed to a record-breaking $83-billion merger with Travelers Group Inc., the insurance company that also owned the Salomon Smith Barney brokerage.

Such a combination was prohibited under Glass-Steagall. But amid high-level lobbying of Fed and Clinton administration officials, the Citicorp/Travelers deal helped spur enactment in 1999 of the Financial Services Modernization Act, which repealed much of what was left of the Depression-era law.

Sanford “Sandy” Weill, the chief executive of Travelers, went on to head the new behemoth, named Citigroup.

In his office on the 46th floor of a Manhattan skyscraper, Weill reportedly hung a piece of wood etched with his picture and the phrase “The Shatterer of Glass-Steagall.” Robert Rubin, the Treasury secretary who helped shepherd the repeal, joined Citigroup’s board in 1999 and later became chairman.

The 2008 financial crisis spurs questions

The early 2000s saw the financial industry grow and consolidate. Large banks competed to sell stocks and securities alongside Goldman Sachs, Merrill Lynch and the other big investment firms.

Complex new financial products were developed. Subprime mortgages, encouraged by federal housing policy, surged in popularity. Wall Street bundled them into securities. Government regulators were lax in their oversight.

The whole thing came crashing down in September 2008, forcing federal bailouts of banks and turning an economic downturn into the Great Recession.

“The erosion and then the repeal of Glass-Steagall was part of a larger deregulatory thrust by the industry and by policymakers that ended up with less oversight, bigger, more complex and more powerful financial institutions — and those bigger, more complex financial institutions took more and more risk,” said Phil Angelides, who headed the federal commission that investigated the crisis.

Would Glass-Steagall make the system safer?

In the wake of the crisis, President Obama and congressional Democrats in 2010 pushed into law a sweeping overhaul of the financial system called the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act.

It didn’t include reinstating Glass-Steagall.

Former Rep. Barney Frank (D-Mass.), who co-wrote the legislation, said in an interview that it would have been difficult to pass the bill with the restoration of those provisions. In addition, Frank said he was worried as the bill was being drafted in 2009 that forcing the breakup of big banks would have added to the financial system’s instability during that precarious period.

But there’s an even bigger reason the separation between commercial and investment banking wasn’t restored in the overhaul: Frank and others didn’t think its removal was a factor in the financial crisis.

Frank, who voted against the 1999 repeal, said that Glass-Steagall restrictions wouldn’t have prevented the issuance of bad mortgages and faulty derivatives.

Other Glass-Steagall opponents point out that the biggest collapses in the crisis were not commercial banks but investment firms such as Bear Stearns and Lehman Bros., and insurer

Dodd-Frank sought other ways to safeguard the system. It toughened capital requirements for banks and required the biggest financial firms to develop liquidation plans so they could be more easily shut down if they teetered near collapse. And the so-called Volcker Rule prohibited banks from trading for their own profit and limited their ownership of risky investments.

But there’s no question that the repeal of Glass-Steagall led to consolidation in the U.S. financial system.

In 1999, the five largest U.S. banks had 29% of total commercial banking assets. By 2008, it was 45%.

The financial crisis and its aftermath led to even more consolidation, as big banks purchased troubled firms such as Merrill Lynch & Co. and Wachovia Corp.

But looking more broadly at the entire U.S. financial sector, the market share of the largest banks has been trending down since peaking in 2010, said Frederick Cannon, director of research at brokerage and investment bank Keefe, Bruyette & Woods.

Large banks are difficult to manage — the unauthorized account scandal at

Reinstating Glass-Steagall would have the biggest effect on JP Morgan Chase, Bank of America and Citigroup — the first-, second- and fourth-largest banks by assets, Cannon said. They all have large investment banking operations. Wells Fargo, the nation’s third-largest bank, has a smaller investment banking footprint.

Splitting up those banks “would give the appearance of safety,” but there could be significant unintended consequences, he said.

“You have the potential to create exactly the type of financial institutions that were at the center of the financial crisis,” Cannon said.

Trump said during the campaign that he wanted to dismantle Dodd-Frank. He has directed Treasury Secretary Steven T. Mnuchin to review the law and its key provisions.

Trump administration officials could try to argue that reinstating Glass-Steagall would offset the risk from eliminating other financial regulations.

Democrats such as Warren and Sanders won’t go for such a trade-off. They want Glass-Steagall restrictions on top of existing regulations.

Angelides said that the largest banks should be broken up, which Glass-Steagall would do, but strong regulations still are required.

“No one should think that gives us the protection we need,” he said.

Twitter: @JimPuzzanghera

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.