Closing of ITT Tech and other for-profit schools leaves thousands of students in limbo

Reporting from Washington — The for-profit college boom has gone bust.

Closures of high-profile schools such as ITT Technical Institute have left thousands of students in limbo while raising questions about the future of an industry that provides training for vocational, technical and other mid-level skilled jobs.

For-profit schools are facing major challenges on several fronts after a period of meteoric growth.

Federal and state officials have filed suits or launched investigations into allegations of predatory lending and false advertising by some leading chains. At the same time, the Obama administration is trying to reshape the industry by pushing new regulations that would tie student debt limits to job prospects and make it easier for students to have their loans forgiven if they were defrauded — with the school potentially on the hook for the tab.

For-profit schools began aggressively expanding their numbers and enrollments in 2000 as online education became more widespread, attracting students who were more likely to be low-income, minority and part-timers.

They’ve done their part of the bargain. They took out the loans to pay for their education. They graduated and what the school promised them wasn’t true.

— Debbie Cochrane, vice president of the Institute for College Access and Success

Those schools ratcheted up their growth even more after the Great Recession, when many Americans sought new skills in hopes of finding better jobs in a tough labor market. Wall Street drove education company stock prices sky-high.

The problems that followed, including high default rates on student loans and accusations of predatory lending, triggered a crackdown by the Obama administration.

ITT’s parent company blamed the administration’s actions for the closure of the chain’s 137 campuses last week, meaning 35,000 students who were preparing to start classes this month won’t get the degrees they were seeking.

Alvaro Laborin, a 36-year-old Navy veteran from Los Angeles, said he spent the last few years working all manner of odd jobs — bartender, mechanic, Uber driver, even a walk-on Hollywood extra — to be able to afford cybersecurity classes at ITT’s Torrance campus.

“It felt like home to me,” Laborin said. “This school has been around since before I was born and now it’s gone?”

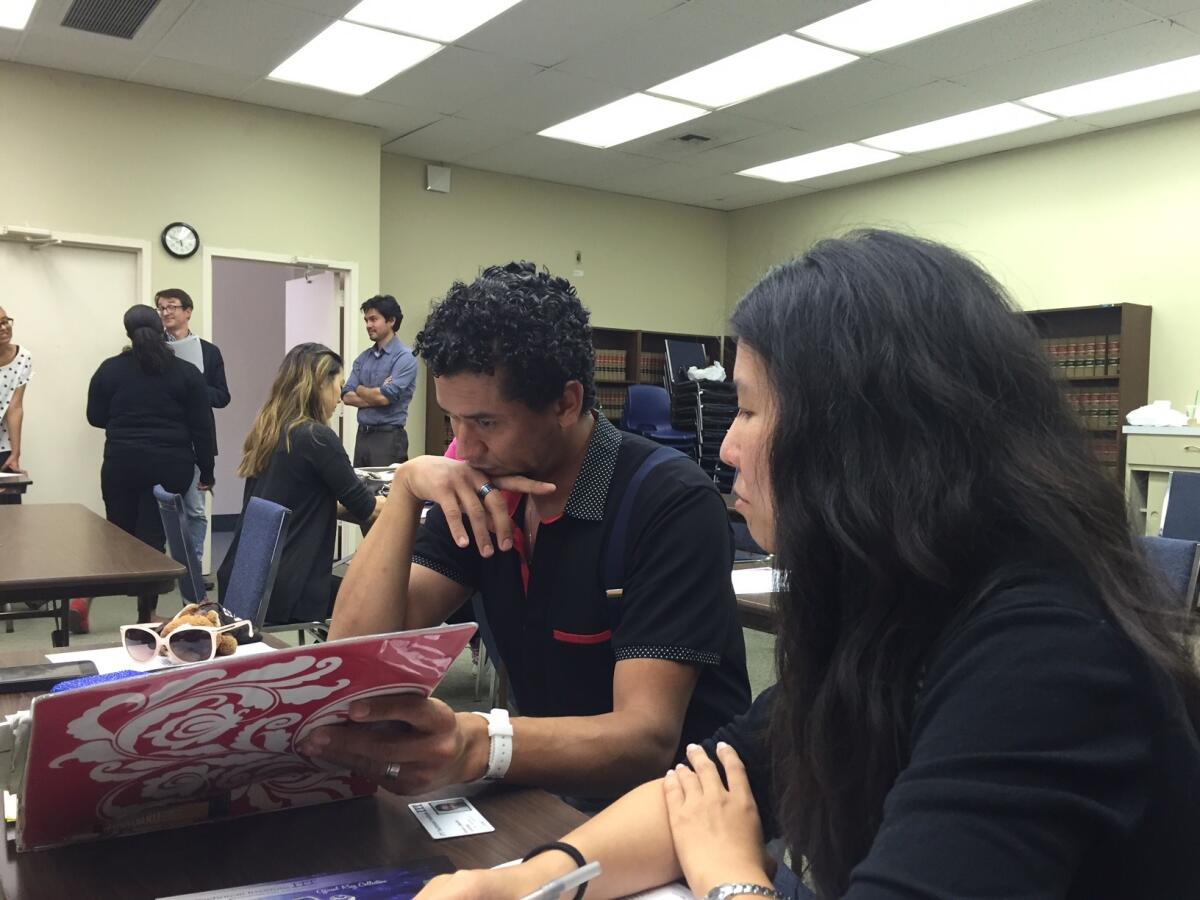

He was among about 20 ITT students at a clinic Thursday night at the offices of the Legal Aid Foundation of Los Angeles to figure out their options. They include trying to transfer ITT credits to other schools or seeking forgiveness on student loans.

Laborin wasn’t sure if he would try to attend another for-profit school or try a public community college. But he said he would not quit on his goal of a college education.

“I’d rather be in debt up to my neck for the rest of my life than give up now,” he said. “When things like this happen, you have to either change or be the one who gets left behind.”

Less than 18 months ago, thousand of students at another high-profile for-profit chain were forced into the same situation. Corinthian Colleges Inc. closed the doors on its remaining campuses following government allegations of falsified job placement rates.

Many students at ITT, Corinthian and other for-profit schools paid for their education by taking out federally backed and private student loans. And though borrowing has shot up at all colleges and universities in recent years, students at for-profit schools led the way.

Their federal student loan originations increased tenfold from 2000 to 2011, according to new research from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

Those students were more likely to default. Many either didn’t finish school or graduated but were unable to land well-paying jobs in their field.

“They’ve done their part of the bargain. They took out the loans to pay for their education. They graduated and what the school promised them wasn’t true,” said Debbie Cochrane, vice president of the Institute for College Access and Success, an Oakland nonprofit group that advocates for broader access to higher education.

Since 2004, annual default rates for students at four-year for-profit schools have been two to three times those of public or nonprofit private institutions, the New York Fed researchers found.

Despite the high-profile closures, the industry is still large. In 2015, there were about 3,500 for-profit institutions, including two-year and four-year vocational and technical schools. That’s an increase of 36% since 2000, according to the New York Fed data.

About 1.6 million students attended those schools. Enrollment nearly quadrupled from 2000 to 2011, with a surge after the Great Recession began in late 2007.

Although enrollment has declined since then 2011, a sharp increase in heavily debt-saddled students has drawn the ire of consumer groups and liberal activists who have accused the schools of predatory lending.

Steve Gunderson, president of Career Education Colleges and Universities, a trade group for the for-profit college industry, acknowledged that there have been problems.

“This sector grew too fast and too much during the recession. We practiced open enrollment and admitted students even if they weren’t academically prepared,” he said. “A lot of students dropped out, had debt and default. We shouldn’t walk away from that.”

This sector grew too fast and too much during the recession. We practiced open enrollment and admitted students even if they weren’t academically prepared.

— Steve Gunderson, president of Career Education Colleges and Universities

But Gunderson and others in the industry have said the Obama administration has unfairly targeted for-profit schools through enforcement actions and new regulations.

The moves threaten opportunities for students to get trained in fields that public and private non-profit colleges often don’t offer, such as truck driving, cosmetology, automotive repair and medical office work, said Gunderson, whose association does not include ITT Technical Institute.

For-profit schools filled educational gaps as many community colleges began offering more four-year degree programs. But after the Corinthian and ITT closures, some community colleges are offering themselves as alternatives for students seeking to transfer their credits.

U.S. Education Department officials said their actions against ITT were designed to protect students, as well as taxpayers who are on the hook for federal student loans that don’t get paid back.

The department forgave about $171 million in debt owed by Corinthian students. About $500 million worth of student loans to ITT students would be eligible for forgiveness, offset in part by about $90 million in insurance ITT had paid to the Education Department, said Education Undersecretary Ted Mitchell.

“We knew when we stepped up our oversight of ITT that this outcome was a possibility and we have been planning for this contingency,” Mitchell said last week of the chain’s closure. “Ultimately, our responsibility is not to any individual institution. It’s to protect all students and all taxpayers.”

ITT students look to legal aid attorneys for answers in the wake of another for-profit school shutdown

Last month, the Education Department barred ITT from enrolling new students who used federal financial aid because of “significant concerns” about the chain’s operations and financial viability.

In 2015, the Securities and Exchange Commission filed fraud charges against ITT Educational Services and the company’s two top executives. The SEC said ITT hid from investors the poor performance and looming financial impact of two private student loan programs the company guaranteed.

And in 2014, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau sued ITT for predatory lending, accusing the company of pushing students into high-cost private loans that were likely to end in default.

Other big players are also facing problems. In January, the Federal Trade Commission filed suit against the operators of DeVry University, alleging its ads deceived potential students about their job and earnings prospects. And the FTC has been investigating the University of Phoenix for similar deceptive marketing practices.

On top of that, other changes will make it more difficult on for-profit schools.

In June, a federal panel recommended the shutdown of the Accrediting Council for Independent Colleges and Schools, which provides the accreditation necessary for many schools to have access to federal financial aid. If the recommendation is approved by Education Department officials, those institutions will have to find another accreditor — and that could be difficult.

See the most-read stories in Business this hour »

At the same time, the Obama administration has toughened regulations of for-profit schools. New rules for schools that offer career training — for-profits and public community colleges with non-degree programs — would limit the amount of debt that students can take out relative to the incomes they can expect to earn with their education.

And this summer, the Education Department proposed new rules that make it easier for students to have loans forgiven if they were defrauded or deceived. The school could be required to pay off the loan balances for claims that are upheld.

The accreditation and regulatory changes add to the pressures of declining enrollments at many for-profit operators, said Trace Urdan, a research analyst for financial services firm Credit Suisse who follows the sector.

“We’re going to see hundreds of schools going out of business,” he said.

Still, most of the for-profit institutions should adapt and survive, Urdan predicted.

“Nobody made the kind of bad decisions on such a big scale that Corinthian and ITT did,” he said.

Follow @JimPuzzanghera on Twitter

MORE BUSINESS NEWS

Democratic senators want hearings on Wells Fargo’s aggressive sales tactics

Tesla stock rises as Elon Musk moves on from ‘one of the worst weeks ever’

HP buying Samsung Electronics’ printer business for $1.05 billion

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.