How the recession changed a family’s path

Members of a Redondo Beach family were looking forward to following dreams that would take them in separate directions. Then the economy tanked.

Five years ago, the future looked bright for Janet Barker and her family.

The eighth-grade English teacher had a secure job with annual raises. Her younger daughter was excited to be starting at UC Santa Cruz. Her divorce was about to be finalized, and she would soon have her small two-bedroom house in Redondo Beach to herself.

After years of tending to others, Barker looked forward to a few indulgences. There would be long-delayed travel to Europe and charity work in Africa. She toyed with the idea of moving to the East Coast.

Then the financial crisis struck in 2008. She has abandoned her dreams, and these days, she's just trying to hold her family together. Five people squeeze into her 1,000-square-foot house because they can't afford to live anywhere else. She's supporting her ex-husband, their daughter, an unemployed son-in-law and a grandchild.

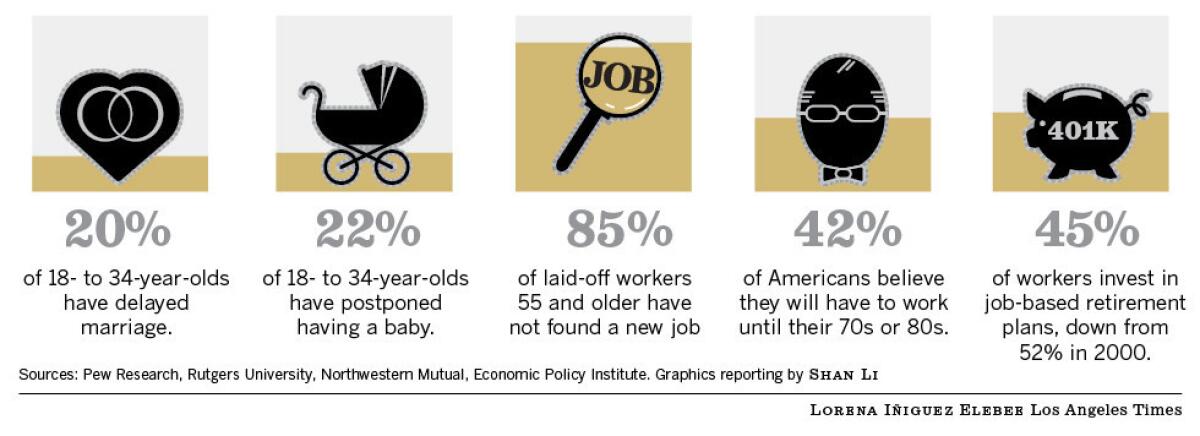

Although the economy is recovering and stock prices are setting records, millions of middle-class Americans have been left behind. Their financial expectations have been greatly diminished.

Income has stagnated. Jobs are still hard to come by. Unemployed people who find work often have to take pay cuts.

The hardships cut across all age groups. Young people are saddled with student debt and have a hard time finding jobs they want after college. Mid-career workers are supporting their grown children and aging parents while worried about their own finances. And older people who lose their jobs may never get another one.

"American workers are between two uncomfortable realities: Either they are working and terrified about the future or they are not working at all," said Carl Van Horn, a labor economist and director of the Heldrich Center for Workforce Development at Rutgers University.

To help pay the mortgage, Barker rents her converted garage to a childhood friend.

A few nights a week, she takes care of her 2-year-old grandson, who sleeps in a crib in her room. There's no space for his mother, Jenny Barker, who stays with friends. Jenny gave up her apartment because her flower shop was struggling.

I don't know how much more I can take."— Janet Barker

Janet, 57, looks on the bright side: The turmoil has drawn her family closer together. She treasures the time with her grandson. She enjoys long conversations with her new son-in-law at mealtime.

"It's sort of like an old-fashioned family," she said. "They used to move under one roof and help each other. That's what we're doing."

But she can't help but wonder how they all slipped so far, so fast.

"I wonder how many other people who look like they're coping are having the same experiences as us," she said. "I don't know how much more I can take."

'Hope and promise'

Janet Barker grew up in Redondo Beach in the 1960s and '70s, infused with a sense of civic purpose by watching John F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr. on her family's sage green Philco TV.

"I lived in the formidable years when there was hope and promise," she recalled. "We were going to make the world better."She married her college boyfriend at age 21. The marriage fizzled but produced two children, Ryan, now 36, a transport expert in aerospace, and Jenny, 33, the floral shop owner.

In her 20s and 30s, Janet worked as a reporter at the Daily Breeze, a newspaper in Torrance, where she met Bruce Hazelton, a staff photographer.

They married in 1986 and their daughter Katie was born four years later. In 1994, the couple scratched together a down payment on a $260,000 California bungalow a block from Pacific Coast Highway.

Today, a white picket fence encircles a property blooming with roses, lavender and a strawberry patch. The mailbox is a replica of the house itself, crafted by Hazelton. The interior is awash in pastel shades of blue, green and pink. A backyard of spruce and silk oak trees serves as an oasis of sorts.

In 2002, Barker changed careers and became a full-time teacher at Parras Middle School in Redondo Beach. The family was careful with spending. There was always enough for a new computer or a bike for Katie.

Barker was better off than her parents, who refolded aluminum foil to use again.

"You couldn't go on big trips and you couldn't go out to eat all the time, but you always had food in the fridge," she said. "It wasn't terrible. It was a step up from the way I grew up, definitely."

The years leading up to the economic crisis were the family's best financially because Barker and Hazelton were both working. And though their marriage was ending, the split was amicable. Hazelton had planned to move out after Katie left for college.Then he lost his job.

Didn't see it coming

One day in January 2009, Bruce Hazelton's boss sent him to the human resources department. There, the 29-year employee earning $52,000 a year was let go.

Hazelton was devastated. He had just turned 60. The economy was tanking, and he wasn't able to get another full-time photography job.

Bruce Hazelton's inability to find a job drove him into a depression. "This illness I had ate away at everything I valued in my life, including my self-esteem, my ego, my drive and my purpose in life," he said. He moved back into his ex-wife's house this year. More photos

Eventually, he looked for any kind of work. The low point came when he was passed over for a job unloading trucks at a department store.

He became disconsolate. He lost his appetite. He barely spoke.

"I liken it to having an undiagnosed cancer of the soul," Hazelton said. "This illness I had ate away at everything I valued in my life, including my self-esteem, my ego, my drive and my purpose in life."

He burned through the $130,000 in his retirement account. He started collecting $1,500 a month from Social Security at age 62. The amount would have been about 30% higher if he had waited five more years before drawing his benefits.

In 2011, three days before Christmas, Hazelton stormed out of the bungalow. He was disgusted with himself and his failure to find steady work.

He stayed briefly with his sister before moving to a veterans' shelter in Long Beach. (He had served in the Navy.) He lived for more than a year in a tiny room painted in what he called "institutional yellow," venturing out only for meals. He avoided contact with other people.

"I was always expecting to get a phone call from his sister saying he's gone, as in dead, as in suicide," Barker said. She called and texted regularly, urging him to come home.

"He needed us," she said. "He needed us to help him to feel good again about himself."

Hazelton moved back to the house this year and sleeps in the TV room.

No safety net

Janet Barker endured her own professional hardship.

Her once-automatic raises were replaced by furlough days that sliced into her income, which is now about $68,000 a year.

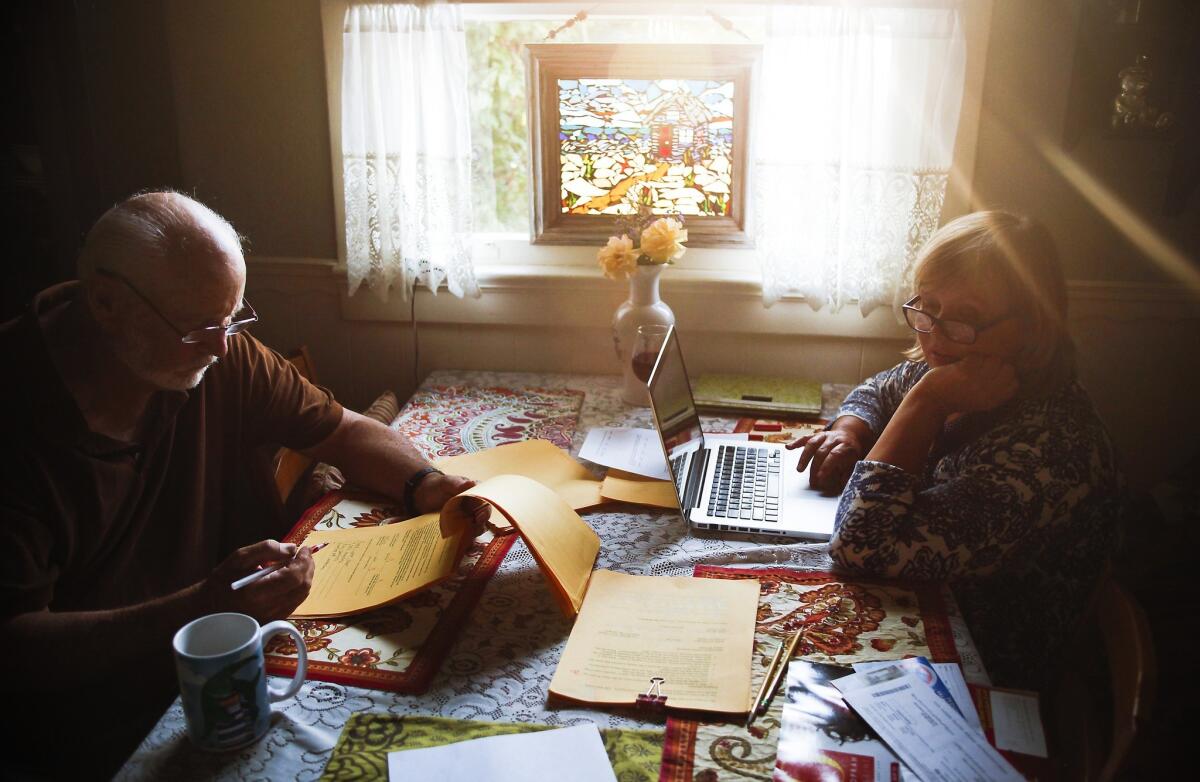

Sitting in her darkened kitchen two weeks ago, a glass of red wine at her elbow, Barker looked at her bank statement with dread. She let out a sigh. Teachers don't get paid during the summer, and her bank account had dwindled.

She had $1,401.50 in her checking account and $2,586.28 in savings. She owed $4,668 on a Visa credit card.

She agonized over paying $24 to Southern California Edison, then $125 on her credit-card debt. The week before, she paid $1,300 on her mortgage and $460 for her share of Katie's student loans.

She finished paying the bills, and started to move $500 into her savings account. She stopped for a second and lowered it to $300. She reconsidered and left the money where it was.

"Oh my God, it's making me sick," Barker said, her eyes teary. "It's like you are hitting a dead end all the time, you are hitting the wall all the time."

She's found hope in playing the lottery. She reasons that God may not want them to struggle forever, and with even a small prize, "we could go out to dinner or something."

Imperfect timing

Katie Barker-Hazelton thought that by the time she graduated, the economy would have rebounded.

Bruce Hazelton, left, Janet Barker, son-in-law Jason Kwok and daughter Katie Barker-Hazelton shop for groceries. In 2008, Barker had planned to live alone and visit Europe. More photos

But she couldn't find a job after earning a degree in sociology last year. Young people like her are confronting the worst employment market for college graduates in decades. She's also become one of 22 million people ages 18 to 34 who live with their parents, up 22% from a decade ago.

She had no luck getting work related to her major or her interest in teaching, and was relieved when she landed a receptionist position at a Torrance antiques dealer with a salary of $1,800 a month after taxes. That enables her to pay $400 a month toward $23,000 in student loans. She contributes to groceries for the household and tries to save as much as $500 monthly for car and other major expenses. She and her husband live on the rest.

"I just thought it was going to be easy when I got out," said Barker-Hazelton, 23. "They tell you, 'Go to college. Get a job. It'll be great. Work hard and you'll get it.' But it really hasn't been that way."

In June, she married her college sweetheart, Jason Kwok, a Hong Kong native, at the Compton courthouse, in part so he could live and work in the United States. They occupy her mother's spare bedroom.

More so than her parents, Barker-Hazelton is mindful of every purchase she makes. She meticulously plans meals to avoid wasting food. She agonizes over buying new clothes.

She chafes at what she views as her parents' wasteful spending.

"They're frugal in many ways, but also careless in ways they don't have to be," she said. "I've talked to her about it. My mom has a gym membership but she never goes to the gym."

Looking ahead

The family eats dinner together. Janet Barker, third from left, no longer dreams about early retirement, but she does speak optimistically about her daughter's future. More photos

Janet Barker no longer dreams about early retirement. She speaks optimistically about Katie's prospects, less so about Hazelton's and her own. Although Hazelton, 64, has secured some freelance photography jobs, he is still looking for full-time work.

Their daughter Katie plans to go to graduate school despite the extra debt it could bring. Their son-in-law Jason is still waiting for a U.S. work permit.

Barker is constantly worried about the family's finances. She had mentioned to her principal that she was interested in teaching another class to make more money. On Thursday, she took on a seventh-grade English class for an extra $40 a day.

It's not much, she admits.

"Are we better off financially? Hell, no," Barker said. "But we are better off in the ways that count, and have always counted since the very beginning. We have had the chance to refocus on what matters."

FIVE YEARS AFTER THE MELTDOWN

Lavish perks take a drubbing on Wall Street

We made a lot of money in those days, and we never thought it was going to end.”

Follow Walter Hamilton (@LATwalter) on Twitter

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.