‘Family Guy’s’ Seth MacFarlane was attacked by this conservative TV watchdog. Now they’re friends

Seth MacFarlane, creator of the irreverent animated show “Family Guy,” once likened the barrage of blistering attacks on the program — and him — from the Parents Television Council to “getting hate mail from Hitler.”

“They’re literally terrible human beings ... rotten to the core,” MacFarlane told a magazine.

The conservative nonprofit railed against MacFarlane and his Fox network cartoon for more than a decade. It petitioned the Federal Communications Commission to proclaim episodes indecent and pressured advertisers to steer clear.

“Whatever would America’s sex-crazed, adolescent potheads do without Seth MacFarlane to amuse them?” the group once fumed. It channeled the outrage to boost membership and fundraising: “To help the PTC fight Seth MacFarlane’s filth, click here.”

In a vitriolic blog post four years ago, a PTC analyst predicted, “Until MacFarlane steps away from his sycophantic audience of frat boys and perverts, and actually stops treating rape and child molestation as jokes, no one will ever respect him.”

Yet, this spring, MacFarlane welcomed an unlikely guest to his stylish offices in Beverly Hills: PTC President Tim Winter. On a Friday evening, the former combatants cracked jokes and engaged in a thoughtful discussion about their beliefs — and friendship.

The two men inhabit such different strata that Winter initially didn’t know what MacFarlane meant four years ago when he suggested they meet at “the Chateau.” Winter called a Hollywood friend for a translation: Chateau Marmont.

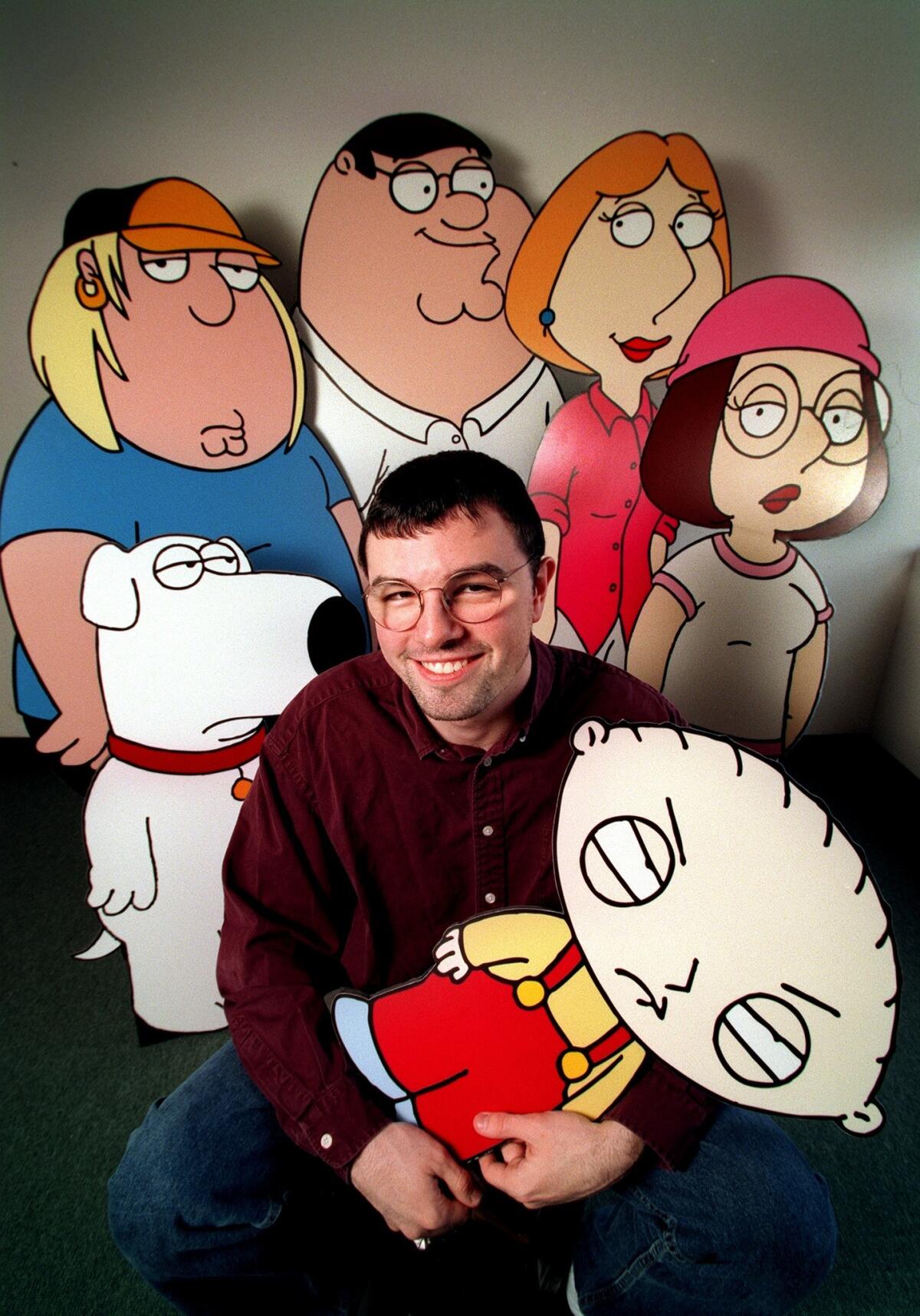

MacFarlane was a 23-year-old student at the Rhode Island School of Design when he created a hand-drawn animated short about a tactless New England father who connected more with the family dog than his son. The project morphed into “Family Guy,” which launched in 1999.

It was the first of many successes for the Connecticut native, now 45, who also co-created the animated “American Dad,” about a CIA agent, and “The Cleveland Show,” showcasing the African American neighbors from “Family Guy.” He branched out to write, direct and star in the popular 2012 R-rated teddy bear buddy comedy, “Ted.”

Fox just renewed for a third season his current pet project, the live-action comedy-drama “The Orville,” which began as an homage to “Star Trek.”

He has released five studio albums. The baritone has long had an affinity for the Rat Pack era; framed images of Frank Sinatra adorn his office.

And MacFarlane still provides voices for main “Family Guy” characters: the blue-collar father, Peter Griffin, whose favorite activity is watching TV; Stewie, the highly intelligent toddler with a British accent; and the talking dog, Brian, who drinks martinis, has sexual fantasies and was once hit by a car but came back to life. (It is a cartoon.)

“Family Guy” was canceled after three seasons, but Fox brought it back to life in 2005 after discovering it was a cult hit on college campuses. But the series has long been an irritant to the Parents Television Council and its firebrand founder, L. Brent Bozell III, who once described MacFarlane as “the guy scribbling graffiti in the bathroom stall.”

Bozell formed the group in 1995 with legendary entertainer Steve Allen to protect children from graphic sex, violence and profanity on TV. The group’s hammer is its ability to pressure advertisers to abandon programs it finds objectionable, prompting criticism from some in Hollywood that PTC’s advocacy borders on censorship.

Under Winter, who became president in 2007, the group expanded its mission to advocate for TV channels to be sold a la carte to give consumers more control over programming. One of the group’s top priorities has been lobbying the FCC to revamp the TV content ratings, and it supports legislation to create a safer internet for children.

“Whatever would America’s sex-crazed, adolescent potheads do without Seth MacFarlane to amuse them?”

— Parents Television Council

Winter, 60, was raised in Virginia by parents with opposing political views — his father a firm conservative who worked at the Pentagon, his mother an aide to an ultra-liberal senator. Winter attended Principia College near St. Louis, where he lettered as a baseball pitcher and majored in business administration.

After graduating in 1981, he moved to Los Angeles and eventually worked as a business executive with NBC, where he spent nearly 15 years, including stints at KNBC-TV Channel 4 in Los Angeles and in London. He also earned his law degree. The married father of an adult daughter (the queen of the 2016 Pasadena Tournament of Roses) joined PTC in 2003.

What brought Winter and MacFarlane together?

In 2015, PTC escalated its attacks on “Family Guy” after an episode in which Peter has surgery to get “two wieners.” The father lifts his hospital gown, swivels his hips (his private parts are not shown) and viewers hear a “thunk.” Peter remarks: “Uh-oh. That was the original.”

PTC called the episode “stupid” and filled with “misogyny ... crude references to sex acts and genitalia … and self-congratulatory narcissism posing as humor!”

That’s when MacFarlane reached out. “I have always remained open to constructive criticism,” MacFarlane wrote in a January 2015 letter, which contained an unusual offer. He invited Winter or two writers of his choosing “to write an episode of ‘Family Guy’ the way you think ‘Family Guy’ should be written.”

The PTC, MacFarlane recalled recently, might have drafted “an awesome, killer script that was funnier than anything that we could have come up with.” But he figured the group might balk. “Then, we could say: ‘Well, if you don’t want to do the job, then don’t criticize the way we do it.’”

The offer stunned Winter, and he agonized over what to do. In a heartfelt letter to MacFarlane, Winter explained the PTC’s goal wasn’t to dictate content but to raise awareness about how some subject matter might harm children. He declined the offer. But he pointed to “at least 58 instances” of jokes about sexual violence during a three-year period on “Family Guy.”

“What is the cumulative impact on children who watched those programs?” Winter wrote. “I humbly and respectfully ask you to help change the dialogue.”

Now it was MacFarlane who was stunned.

“I was properly humbled,” MacFarlane said, “and I figured that I gotta give him a call.”

When the phone rang in Winter’s downtown Los Angeles offices, late on Good Friday in 2015, Winter assumed it was a prankster. But after Winter was convinced that it was MacFarlane, the two men began a conversation, which resumed a few weeks later in Hollywood at the Chateau Marmont, an entertainment industry mecca.

At their recent meeting, Winter acknowledged being nervous about getting together.

“We had taken some pretty serious potshots,” Winter, said, looking at MacFarlane, who sat across from him at a conference table. “I never want to make a beef personal ... but we called you out by name in our fundraising pieces.”

Over drinks and dinner, which stretched three hours, the men discussed TV’s influence on society and the potential effects of raunchy entertainment on children.

“My parents let me watch ‘Animal House,’ ‘Caddyshack,’ ‘Stripes’ ... these R-rated comedies when I was 7,” MacFarlane said. “I had a very strong family unit and so there wasn’t much damage that was done from those films… . But when your kid is being raised by TV, it could be a different story.”

Now, he has a greater appreciation for the PTC and its work. “I think it is a healthy, necessary thing for them to exist in the same world as what we are doing,” MacFarlane said.

The two men have an easy rapport.

“Do you remember the first thing you said when we got together at the Chateau hotel?” Winter asked MacFarlane, who offered: “Was it: ‘Man, I shouldn’t have driven here.’”

Winter quipped: “No, that was on the way out.”

Although neither admits it, they appear to have had an influence on each other.

Since their first meeting, Winter said he’s noticed a change on “Family Guy.”

“There was not one single joke about sexual assault for more than three years — until a couple of weeks ago,” Winter told MacFarlane.

MacFarlane looked puzzled. “Really?”

Winter mentioned a January episode that featured a cartoon President Trump groping Meg Griffin, the 18-year-old daughter. Fondling was not depicted, just Meg’s horrified reaction.

MacFarlane smirked. “That’s more ‘holding a mirror up to society,’” he playfully protested. (The scene riffed on Trump’s comments about grabbing women, captured in the infamous “Access Hollywood” tape.)

“If the president of the PTC and the creator of ‘Family Guy’ can have this kind of a relationship, maybe other folks might be able to try to do the same.”

— Tim Winter

The two men clearly enjoy each other’s company. Although they rarely meet, they converse via texts. They’ve talked about politics, the media, global warming and even plot points from “The Orville.” When Winter’s mother fell ill a few years ago, he bought her MacFarlane’s music CD “No One Ever Tells You.” When she died, MacFarlane provided solace by sharing emotions he experienced when his own mother passed.

MacFarlane acknowledges that he’s matured.

“When I was in my 20s, I had a bit more simplistic view,” MacFarlane said. “The older that I’ve gotten, my perception and opinion of how television and TV and film storytelling relates to changes in the social fabric alters almost daily.”

While some continue to view MacFarlane as the brat who sang “We Saw Your Boobs” when he hosted the Oscars, that’s not the full picture.

“Seth is a truly open-minded person,” Rich Appel, who now oversees “Family Guy” as its executive producer, said in an interview. “If he hears something that makes sense to him, then he will refine his own position. He’s never going to shut the door in someone’s face.”

And, over the years, “Family Guy” also has evolved, which is no surprise, Appel said. “But do I think the show has changed in response to the PTC’s criticisms?” he asked. “Respectfully, no.”

MacFarlane said he wasn’t sure whether his friendship with Winter rubbed off on “Family Guy” because he hasn’t written an episode in eight years. Still, he is trying to move beyond his potty-mouth persona.

And he is channeling the change through “The Orville,” in which MacFarlane plays Capt. Ed Mercer, a kindly 25th century military man who commands a starship, “The Orville,” as he tries to mend his broken life.

MacFarlane found fans in an improbable place.

“The Orville” has “morphed from slapstick, juvenile comedy into a much more thoughtful sci-fi drama,” a PTC analyst wrote in a recent review. The show, she wrote, tackled weighty topics, such as pornography, genocide and social media, with “surprising maturity, sophistication, and with ultimately pro-social messages — a far cry from the ‘rape is funny’ messages of ‘Family Guy.’”

MacFarlane said “The Orville” was inspired by a nostalgia for “Star Trek” and “The Twilight Zone,” shows he consumed as a kid. “Those scripts showed a real moral compass at work,” he said. “And as silly as it sounds, it was influential to me that their weapons were kept on stun.”

After seeing “The Hunger Games,” MacFarlane became concerned that too much entertainment focuses on dark themes and brooding antiheroes.

MacFarlane also worries about the effect of Twitter and other social platforms filled with “faceless mobs who go after other people” who have opposing views. When it comes to Twitter, MacFarlane said he may be more in sync with a PTC point of view.

And they agree on something else. The group that once sought donations to counter “MacFarlane’s filth” now recommends that advertisers buy time on “The Orville.” “Even the most conservative people on our staff love it,” Winter told MacFarlane, adding, “I want to do everything we can to help it succeed.”

Sounds like the pat resolution of a sitcom, but MacFarlane said there are real-life benefits to escaping “your own little bubble” and engaging people with different opinions. “You find out that you have a lot more in common than you initially thought,” he said.

Winter summed it up: “If the president of the Parents Television Council and the creator of ‘Family Guy’ can have this kind of a relationship, maybe other folks might be able to try to do the same thing.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.