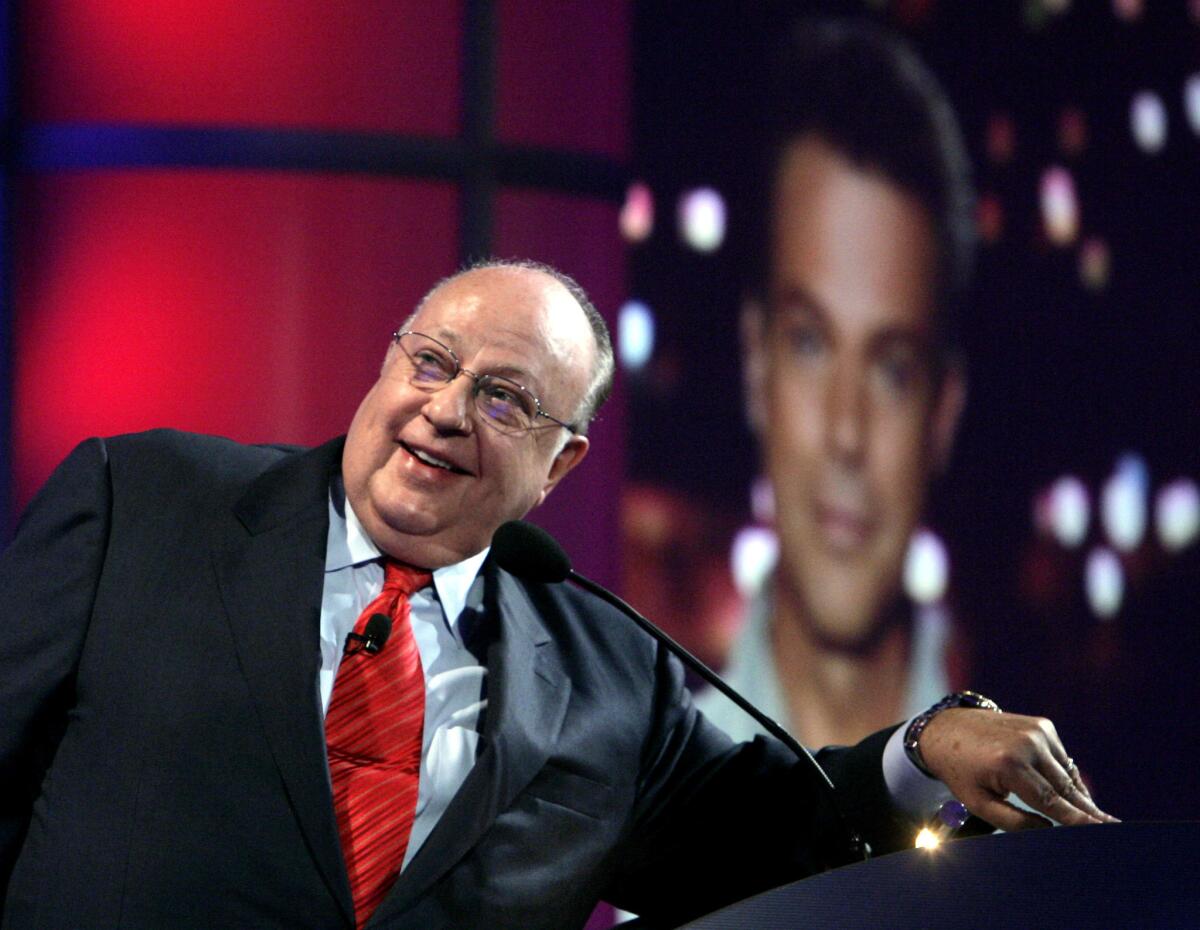

How I survived Roger Ailes’ wrath in 1988: ‘He wanted to beat you up a little bit’

Before Roger Ailes made TV history with the launch of Fox News, he was considered the best political media strategist in the business.

I first got to know Ailes in 1988 when I was a writer for the advertising trade magazine Adweek. An all-star lineup of creative ad people earned kudos for the gauzy “Morning in America” commercials made for Ronald Reagan’s 1984 reelection campaign.

Four years later, Madison Avenue’s involvement in the election became my beat. Ailes was tapped to lead the GOP team handling the presidential campaign of then-Vice President George H.W. Bush.

Ailes, who died Thursday at the age of 77, already had a reputation for being an outsized character. It was Ailes who also convinced Richard Nixon that mastering TV was the only way to win the White House in 1968, as well documented in Joe McGinniss’ classic book “The Selling of the President.” (Ailes told McGinniss the public looked at Nixon as “the kind of kid who always carried a book bag. Who was 42 years old the day he was born.”)

After reading it, the weeks it took to get a meeting with Ailes felt like months. When we got together at his Manhattan office, Ailes still wore a demonic-looking goatee that made him look slightly intimidating. He was candid and profanely funny — saying things that even in 1988 were inappropriate to laugh at, but I did.

Just as he did with Nixon in 1968, Ailes oversaw a repositioning of Bush, which was required after the patrician vice president had been on the cover of Newsweek with the headline “Fighting ‘The Wimp Factor.’”

Ailes was in the room as Bush pushed back against Dan Rather when the anchor of “The CBS Evening News” raised the arms-for-hostages scandal that engulfed the final years of the Reagan administration. A biographical ad for Bush used footage of him being fished out of the Pacific Ocean when his plane was shot down during World War II. He was being de-wimped by the week, and got the nomination.

But Ailes wasn’t finished. There was the question of a running mate. The choice made at the Republican National Convention in New Orleans that summer was a surprise — Dan Quayle, the junior senator from Indiana.

Pundits praised the move. Likability was still an issue with Bush. who was way behind Massachusetts Gov. Michael Dukakis in the polls. The campaign needed a jolt and Quayle seemed youthful, telegenic and fresh next to a vice president who had been around for eight years.

The day after Quayle was chosen, I ran into Ailes on the floor of the Superdome, where the 1988 convention was being held. He was getting ready to rehearse Bush’s acceptance speech when I asked him whether he had something to do with the Quayle choice. Ailes had done the advertising for Quayle’s landslide senate reelection win in 1986, the year a number of other Republican Senate incumbents were voted out.

“I suggested it,” Ailes told me with a look on his face that suggested he regretted taking the question.

By the last day of the convention, the reaction to Quayle had shifted. There were reports that questioned his use of family influence to get assigned to National Guard duty during the Vietnam War. It was a negative story that stepped on Bush’s night in which he had given the political speech of his life.

The brilliant choice suddenly was not looking so great. The fact that it was driven by the guy in charge of the commercials made it look worse. The headline of my Adweek story about Ailes’ involvement used a quote from a Democratic ad maker who said the Quayle selection was “Media Consulting Run Amok.”

The phone rang soon after I got to my desk in New York the following Monday morning. It was Roger Ailes. People told me he could get volcanic when mad. They were right.

He tried to deny his role in the Quayle choice. I reminded him that not only had he told me, but that Sen. Bob Dole had also brought it up on “Meet the Press.”

“Bob Dole’s crazy because he lost his arm in the war!” Ailes said. Or yelled. He finished the conversation by saying I was “dead” to the campaign and anyone in it who talked to me in the future would be fired.

I called Sig Rogich, a Las Vegas ad executive and Ailes associate who was my connection to the advertising team. “Don’t worry about it,” he said. “He wanted to beat you up a little bit, but he’ll get over it.”

The Dukakis campaign tried to make Ailes an issue, even creating a series of commercials called “The Packaging of the President.” It showed actors portraying a group of conniving Bush handlers in a smoky back room coming up with ways to gloss over their candidate’s record and distort his opponent.

The spots didn’t work. The Quayle controversy died down and Bush went on to win, largely with the help of the ad team led by Ailes that stuck with a strategy of making Bush look more presidential while presenting Dukakis as a liberal risk. (Bush tweeted on Thursday that he might not have become president without the help of Ailes.)

Later on election night, after Bush had been declared the winner, I received a phone call at home from Ailes. Why would Ailes call an ad business reporter on a historic night? But I wasn’t surprised to hear from him. I had learned a lot about political consultants that year. They all coveted corporate work. The money was better than politics and the travel schedule far less onerous. When consultants got fired in the 1980s, they did not have three cable news channels where they could become on-air contributors. One consultant told me how as a breed they feared dying alone in a hotel room.

Ailes talked to me because he wanted Adweek’s readership of marketing executives to know that as a fast-acting media tactician, he was ready to do for their brand what he did for Bush. “I’ve proved that I could do it,” he said.

He was aware that his edges were a little rough. I asked him about calling Dukakis “the meanest little son of a bitch” in American politics. His answer offered some insight on the bare-knuckle style he later used in getting Fox News on the map.

“I may have been exaggerating,” he told me. “But it was necessary to direct my team, to tell them not to take the other side lightly. They’re not some small-state politicians. I wanted to fire a shot across the bow to show the Democrats we were aware of that.”

Nearly 12 years later, Ailes’ office called and asked me to join him for lunch at a restaurant near Fox News headquarters on the Avenue of the Americas. He was finishing out his first contract as the head of Fox News, which had not yet become the cable powerhouse it is today. It was the height of the dot-com bubble in 2000. I was working for Inside.com, a media news website.

Ailes confided that he was not sure he would re-sign with Fox News. He was getting approached by Internet companies. He wanted me to tell him everything I knew about the Web, which wasn’t very much. But he hung on every word.

The rest is history. Ailes decided to stay with Fox News, and within two years it surpassed CNN to become No. 1 in the ratings, where it has been ever since.

Read the rest of The Times’ coverage of Ailes here.

Twitter: @SteveBattaglio

ALSO

Roger Ailes turned television news into an Us vs. Them free-for-all

Conservative media remember Roger Ailes as ‘brilliant’ but flawed TV executive

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.