How NBC’s ‘Must See TV’ risk takers of the ’90s are still launching groundbreaking TV

Twenty-five years before Peak TV, there was “Must See TV.”

The three words served as the marketing tagline for NBC’s lineup of prime-time hits during the 1990s, when the country was still talking on mobile flip phones and the proliferation of cable channels was the biggest threat to the mighty broadcast networks. If you wanted to binge on a TV series, you had to buy a DVD box set.

NBC typically reached 75 million viewers on Thursday nights during much of the 1990s, more than ABC, CBS and Fox combined, with hit shows such as “Friends,” “Seinfeld,” “Mad About You,” “Frasier,” “Will & Grace” and “ER.” The network also racked up the most Emmy wins and nominations during the decade while generating annual profits in the range of $500 million.

More than two decades on, Must See TV still matters, and not just as a nostalgia kick.

The traditional TV landscape where NBC once ruled has been disrupted by the rise of prestige shows on premium cable and online streaming services. All the broadcast networks are scrambling to hold onto their diminishing audiences and cultural relevance. But the demand for the people who developed the arsenal of NBC’s high-quality hits of the 1990s — many of which have sustained their popularity thanks to online streaming — has remained. Must See TV veterans have helped shape some of the most groundbreaking shows of the Peak TV era, including “Homeland,” “The Handmaid’s Tale,” “Atlanta,” “The Americans,” “Orphan Black,” “Fargo” and “The Shield.” And five executives from the Must See TV era, are currently running network TV entertainment operations.

That’s partly due to timing. The executives who were in their 20s and 30s during their NBC years are now seasoned pros who have the experience of developing broad-appeal hit shows and maintaining their quality over 22 episodes in a season, an increasingly valuable skill in a market crowded by an explosion of TV programming options.

“Whether they succeeded or failed, the training they received during that era was incredible,” says Ted Harbert, a veteran network executive who was at ABC during NBC’s reign. “You just can’t find that anymore.”

Karey Burke, 52, who was part of the program development team that put “Friends” on NBC, became president of ABC Entertainment in November after overseeing the revamp of parent Walt Disney Co.’s Freeform cable channel.

David Nevins, 52, who shepherded “ER” and “Will & Grace,” was elevated to chief creative officer at CBS in October after eight years of heading the company’s premium cable channel Showtime, which is still part of his portfolio.

Nevins’ team at NBC included Kevin Reilly, 56, the current president of TBS and TNT, who recently added WarnerMedia’s upcoming streaming service to his duties.

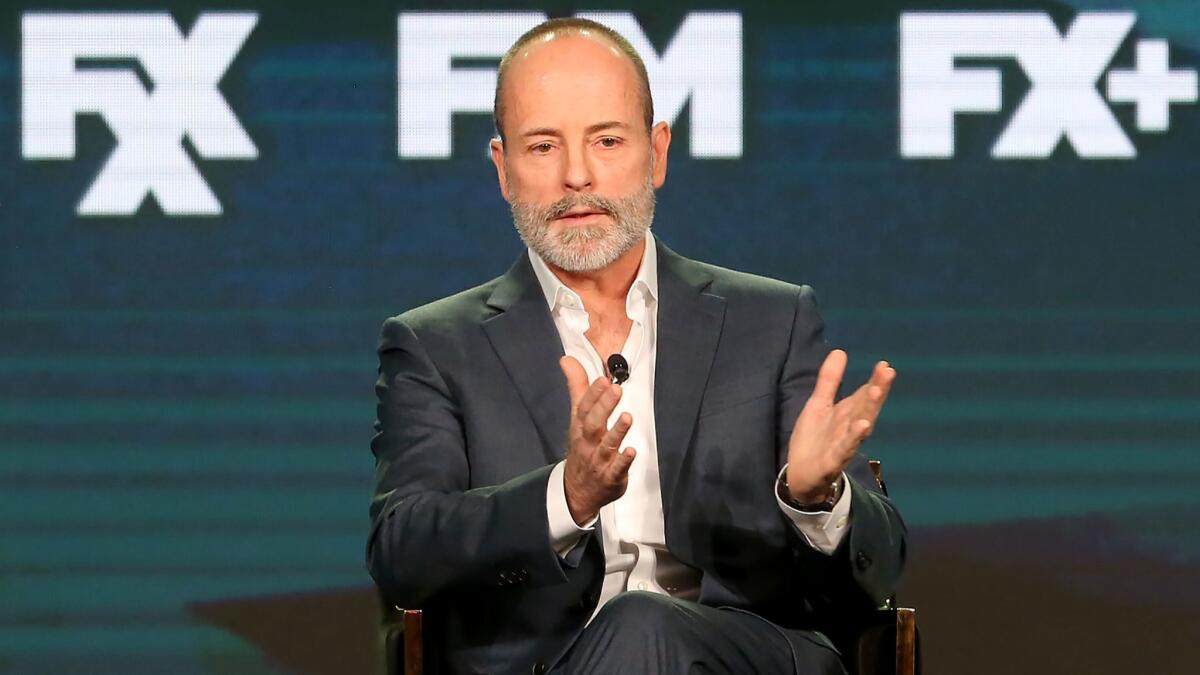

John Landgraf, 56, has led FX Networks — the home of such critically lauded series as “The Americans” and “Atlanta” — since 2005 and is continuing in that role following the company’s ownership change from Fox to the Walt Disney Co. His NBC tenure ran 1994 to ’99 and he worked on “Friends,” “ER” and “The West Wing.” He also coined the term “Peak TV,” which characterizes the bounty of scripted programming choices viewers have today.

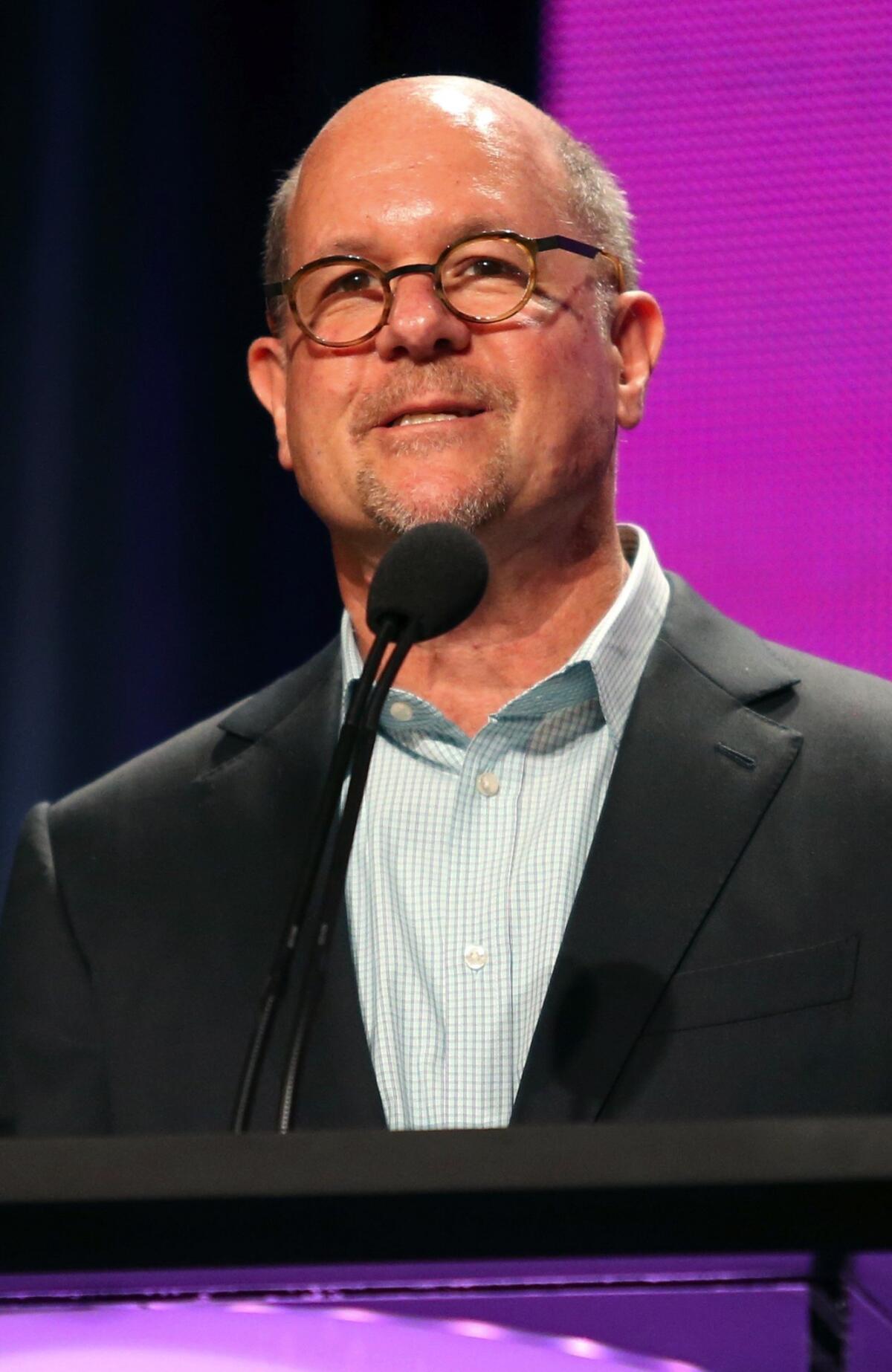

Even public television has some Must See TV lineage. Perry Simon, 64, named chief programming executive at PBS in early 2018, was at NBC from 1983 to ’93. In recent years he commissioned the cult favorite “Orphan Black,” when he headed cable network BBC America.

Risk takers

Three of the group’s former colleagues have served as network entertainment chiefs in the past: Jamie Tarses and Steve McPherson had stints at ABC while Tom Nunan ran UPN, the network that was eventually merged into the CW. Reilly also served as an entertainment chief at FX, Fox and in the post-Must See era at NBC from 2003 to ’07.

All of them worked under Warren Littlefield, 66, the NBC entertainment chief from 1991 to ’98, whose current production outfit, the Littlefield Co., has been a major contributor to television’s creativity surge with Emmy Award-winning series for FX (“Fargo”) and Hulu (“The Handmaid’s Tale”). The latter was the first streaming series to win a trophy for outstanding drama.

“Warren had tremendous taste and really elegant leadership,” says Nunan, a partner at Bull’s Eye Entertainment and a lecturer at the UCLA School of Film, Theater and Television. “You felt good coming into work every morning with him there. He obviously had excellent taste in picking executives.”

The shared corporate DNA of the executives has kept them connected. They still see each other socially and have reunited on industry panels to reminisce about their triumphant years.

“There is a camaraderie among the people who worked there,” Nevins says. “We all have warm feelings for each other.”

They have also adhered to the philosophy drilled into them during their NBC tenures. While creating hits was their main goal, so was having the courage to take risks and standing up for projects.

“There was a forgiving nature about the way you worked creatively,” says Nunan, who oversaw NBC’s production studio from 1995 to ’98. “Everyone was expected to work very hard to be relentless about finding bold new voices out there. If you messed up — they still believed in you.”

Even with a mandate to trust their instincts, it was not always easy.

Littlefield keeps a framed copy of the dismal audience testing report for the pilot of “Seinfeld” on his office wall. The research predicted failure for a show that became one of the most successful sitcoms of all time, earning more than $4 billion.

“[‘Seinfeld’ creators] Jerry Seinfeld and Larry David didn’t know the rules and followed their heads and their hearts,” Littlefield recalls. “For the most part we were smart enough to get out of the way.”

Nevins can remember clashing with Don Ohlmeyer, a cantankerous NBC senior executive who hated the pilot for “ER,” the hit medical drama that played like an action movie.

“I was devastated at first, “ Nevins says. “But sensory overload is what made it compelling. I always believe the audience can process more and faster than producers and the Hollywood establishment once believed. Give them an emotional roller coaster.“ The viewers eventually proved Nevins right.

Nevins also got pushback from Ohlmeyer when he touted “Will & Grace,” a sitcom with two gay lead characters, unheard of for broadcast TV in 1998. (“What world do you live in?” Ohlmeyer asked). But Nevins persevered and the series became a major hit and a cultural milestone and helped alleviate prejudice against the gay community.

“My mother worked in Orange County in a very conservative insurance agency,” Burke says. “She was overjoyed to tell me that ‘Will & Grace’ was doing some good in the world.”

Nevins says his triumphs at NBC taught him to stick to his guns when it came to bold programming ideas. At Fox, he championed “24” — the addictive series that told a single story about an anti-terrorism unit in real time over 24 episodes. He moved Showtime into TV’s creative vanguard with “Homeland” and “The Affair,” and brought a lot of attention to the network with the revival of David Lynch’s cult favorite “Twin Peaks.”

“I always think about what’s going to drive the medium forward,” Nevins says. “Forget about what’s working right now.”

‘First be best’

Key to the success of “Must See TV” was establishing a creator-friendly ethos. Landgraf says he has tried to bring that ethos to FX, which emerged as a haven for such producers as Ryan Murphy (“American Horror Story and Noah Hawley “Fargo”) under his watch.

“One of the reasons people like working at FX is because they really think that we know their shows and care about them and our fans,” Landgraf says.

While there was plenty of internal tension at NBC during those Must See years, the executives say the atmosphere was largely a nurturing one that had long-term benefits.

“I think those guys, and they were guys, valued teaching the next generation,” says Burke, who first joined the network after she graduated college in 1989. “It was important for them.”

Littlefield believes the template that his executives followed was set in the early 1980s when Grant Tinker, whose MTM Productions created “The Mary Tyler Moore Show” and other heralded series, was hired as chairman of NBC when it ran a poor third in a three-network universe.

“First be best, then be first” became the mantra at NBC under Tinker. He told his creative team to put on the shows they would watch rather than following previous management’s dictum of finding the “least objectionable program.”

“Grant would look at us and say, ‘the audience is not the other, they are you — they are young, highly educated adults who love this medium. Make the shows for you,’” Littlefield says. “‘Find the best ideas and the best people and let them in fact do what they do.’”

The approach allowed Brandon Tartikoff, Littlefield’s boss at the time, to stick with creatively strong shows that were slow to find big audiences. The patience paid off as Emmy-winning series such as the groundbreaking police drama “Hill Street Blues” and the grown-up ensemble comedy “Cheers” became hits. They also learned to have fun.

“Brandon reminded everyone that there’s no better job on the planet than being at a network, developing shows, and that anyone could walk through your door and change your life and the life of your network,” Littlefield says.

The success emboldened them to take chances. In 1984, Tartikoff, Littlefield and Simon moved ahead with a series pilot based on Bill Cosby’s stand-up comedy. The half-hour sitcom genre was considered dead. But “The Cosby Show” became the most-watched show on television for five consecutive years and turned NBC’s ratings fortunes around. (“The Cosby Show” reruns earned a fortune for decades until the 2018 conviction of its star, who was accused by multiple women of sexual assault, prompting stations and networks to drop the show.)

“That was something I took with me my entire career,” says Simon. “Don’t be afraid to reinvent things in new and fresh ways.”

NBC slipped in the ratings in the early 1990s as its hits aged and viewers acquired more cable channels. Littlefield moved NBC more toward sophisticated adult comedies — often set in urban centers, which attracted upscale audiences favored by advertisers.

“These were shows that were extremely specific, original and well-written in terms of their characters,” Landgraf says. “You knew what the four main characters would do or not do on ‘Frasier.’ The same for ‘Mad About You’ and ‘Seinfeld.’”

Once “Friends” and “ER” debuted in 1993, becoming huge hits in their first season, NBC was back on top for the rest of the decade.

“The incoming calls from people who wanted to be on the shows in those days — everyone wanted to be on ‘Friends’ — created the sense that this was pop culture at its most pervasive and most relevant and most fun,” Burke says.

A new audience

The durability of the Must See TV hits have made them popular on streaming platforms that needed proven programming to build audiences.

Netflix paid more than $100 million last year to keep the rights to “Friends” for another year. Viewers and TV critics rediscovered “ER” last year when it debuted on Hulu. Twenty years after its finale, “Seinfeld” repeats are still ubiquitous on broadcast and cable TV and it’s a hit on Hulu. The last major Must See hit “The West Wing” — which disproved a Hollywood axiom that a Washington-based drama would never work — has seen a recent resurgence among the streaming audience as viewers seek a distraction from the chaotic Trump presidency.

Fans have clamored for reboots and reunions of the Must See TV hits and in some cases they have been rewarded. NBC revived “Will & Grace” and cable company Spectrum has bought a reboot of “Mad About You.”

The executives who worked on developing and sustaining those series when they first ran now tell stories of how their children have discovered them.

Burke was the director of comedy development when the network launched “Friends.” Years after it ended its run, she watched her kids become fans of the series. It made her aware of the show’s timeless appeal.

“My daughter was in middle school when I gave her the DVD box set for Christmas and we spent the Christmas break all watching it together,” Burke recalls. “She was having some trouble with her friends at school at the time. When she was ready to go back I said to her ‘are you going to be OK?’ She said, ‘It’s OK mom, I have my friends — I have Monica and Chandler and Joey. It’s going to be all right.”

NBC’s dominance ended in the early 2000s. Littlefield was gone and the competition made headway with big, unscripted TV hits — ABC’s “Who Wants to Be a Millionaire,” “Survivor” on CBS and “American Idol” on Fox. Must See TV comedies eventually gave way to NBC’s own reality hit “The Apprentice” in 2004 (which also paved the way for the unlikely ascension of its star, Donald Trump, to the White House).

For Landgraf, the turning point for the TV industry came in 1999, when he was summoned to a meeting at NBC headquarters in Burbank to take a look at a new device called TiVo — the first digital video recorder.

The networks’ ability to dictate when audiences could watch their shows had been the key ingredient for building a mass audience. That would forever change with new technology in the black box that gave viewers the freedom to watch programs on their own time.

“It was ominous,” Landgraf says of the meeting.

But Littlefield will always have the memory of the neighborhood strolls he took around New York City during those Must See years, which allowed him to experience the network’s dominance first hand. Through apartment windows he could see TV screens illuminating living rooms as people watched NBC’s hits.

“It was absolutely thrilling,” he says. “I’d do that for a couple of hours and then I’d slip into some dive and have pizza and a beer and it was a complete pinch-me moment.”

Twitter: @SteveBattaglio

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.