The NFL scandal shows why you shouldn’t get your news from the PR dept.

The purchase and sale of news reporters by powerful institutions and influential people are hardly a new phenomenon. But like all manifestations of disproportionate wealth, it’s been raised to glorious new heights during the early 21st century.

Not only are journalists suborned by “access” into seeing things their bidders’ way--access to company CEOs, access to entertainment and sports stars, advance access to the next Apple product--but increasingly they’re directly employed by the companies they’re supposed to be covering objectively.

The folly of these arrangements is now vividly on display, thanks to the travails of the National Football League. As Stefan Fatsis documents in a superb piece at Slate.com, some of the nation’s most experienced and dedicated football reporters have downplayed the Ray Rice scandal in their work. Why? Because they work for NFL.com.

Others, like Peter King of Sports Illustrated and Adam Schefter of ESPN, have been accused of uncritically taking the NFL’s side in a case in which the league’s actions continue to look worse. (Schefter after Rice’s two-game suspension: “Was the commissioner lenient enough?”) They don’t work directly for the league, but their careers are highly dependent on their image as NFL “insiders.”

The risk for reporters of relying on access to the mighty is that they can get played, ruthlessly. The risk to their readers and viewers is that important information, defined loosely as anything the subject doesn’t want the public to know, gets suppressed.

Sports leagues have been especially aggressive in setting up their own news operations, complete with promises that management doesn’t interfere--no, not one bit--with the articles they publish. That line of malarkey was punctured in March, when we reported the revealing words of Dodgers PR boss Joe Jareck. Perhaps thinking that he was safely out of American earshot since he was in Australia, Jareck confided to an audience that the team runs its own news website, Dodgers.com, because then “we can spin it any way we want.”

What’s dangerous about big companies and institutions publishing their own “news” isn’t merely that they’ll lie, although they will. It’s more subtle: even the most honest and dedicated reporters employed by BigBusiness.com will self-censor, perhaps subconsciously, because they know they’re working in their employer’s interest, not the public interest.

To a certain extent, journalists have always been at risk of becoming “captured” by their sources, or their subjects; it takes a high degree of professional discipline to fight the magnetic tug, and the best journalists make their careers that way.

But the closer one is to the center of power, the less inclined one might be to write a report that will get one bounced from the inner circle. Most reporters working in the crucible of the White House, or Congress, or a competitive business beat, feel the tension between what Dean Starkman, formerly of the Columbia Journalism Review and shortly to join us here at The Times, calls “access” and “accountability” reporting. (H/T to Stefan Fatsis for picking up on Starkman’s point.)

In his book, “The Watchdog That Didn’t Bark: The Financial Crisis and the Disappearance of Investigative Journalism,” Starkman observed that “access reporting tends to talk to elites; accountability, to dissidents.”

Politics, business and entertainment are especially vulnerable to the primacy of access. The political reporter I.F. Stone once issued a withering judgment of the quintessential access journalist Theodore H. White, whose “Making of the President 1960” was chock full of insider nuggets delivered by sources who received, in return, fulsome praise in the pages of White’s best-selling book: “A writer who can be so universally admiring,” Stone wrote, “need never lunch alone.”

TV and movie starts know they can find a warm welcome on the “Today” show; CEOs and investment magnates know they can snuggle into the studios of CNBC.

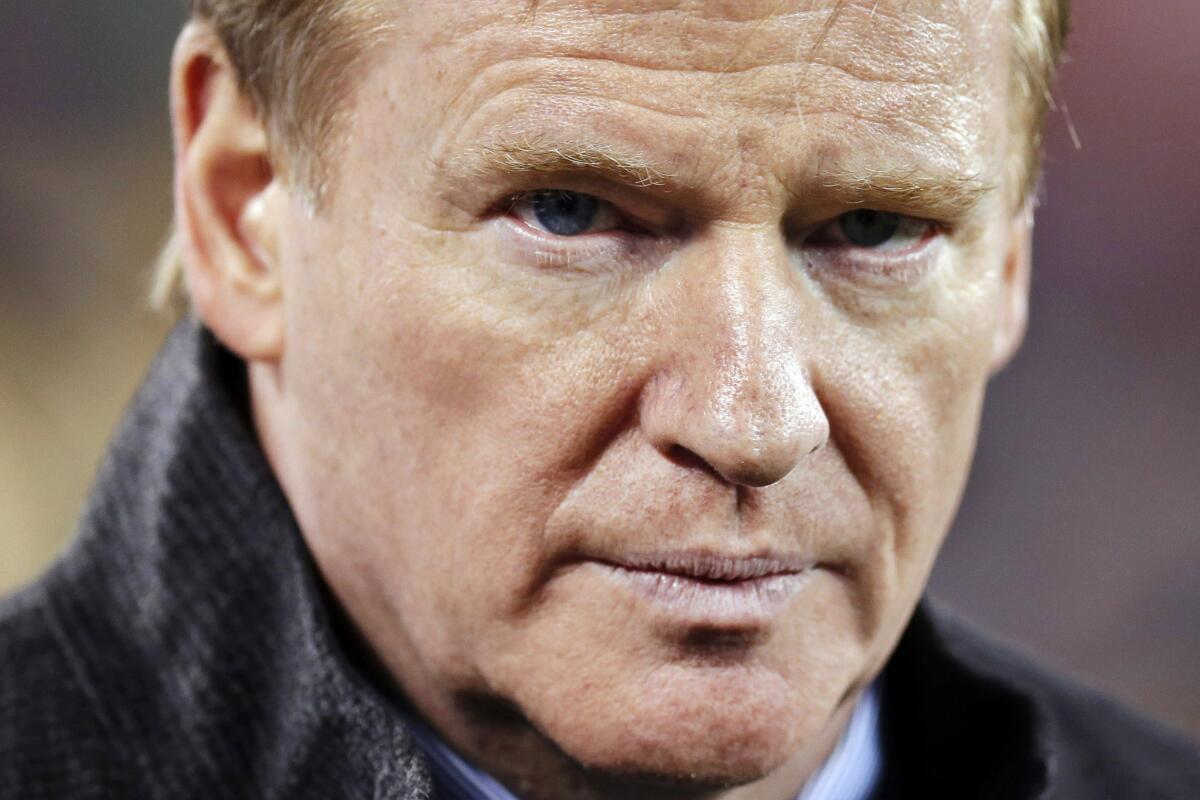

The loudmouthed sports site Deadspin, part of the Gawker Media stable, labels itself as offering “sports news without access, favor or discretion”--the latter two qualities are handmaidens of the first. Its information about the NFL scandals may not be the freshest, but its takes about the actions of NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell have been customarily uncompromising. If you like that sort of thing.

That’s why outsiders are often responsible for the biggest news breaks. Watergate was initially exposed not by members of the White House press corps, but by a couple of police reporters named Woodward and Bernstein. The Ray Rice video wasn’t acquired and aired by members of the NFL press corps, but by the scandal-mongering upstart TMZ.

The sports leagues and companies that set up their own news outlets pretend that their only goal is to provide useful information to fans, customers or members of the public who can no longer get it from a fragmented news industry. That’s a scam; powerful entities have always resented having their public statements filtered by skeptical intermediaries in the press--or worse, having their secrets exposed.

The claque that praised Roger Goodell initially for his judicious handling of the Ray Rice affair, then defended him when the first glimmers of incompetence emerged, are now joining in the pillorying brigade. But the extent to which they were suborned by the league is exposed. Think of how little we would know about Ray Rice and Adrian Peterson today if our only source of information about pro football was NFL.com.

Keep up to date with The Economy Hub by following @hiltzikm.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.