Column: The myth of ‘consumer-driven healthcare’ comes to life again

President Obama, flanked by White House aide Valerie Jarrett, left, and Health and Human Services Secretary Sylvia Mathews Burwell, delivers remarks on the Affordable Care Act in February.

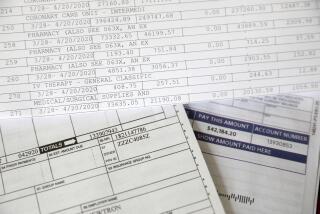

Among the holy grails of would-be healthcare reformers, the holiest and grailiest quest is for the “empowered consumer.”

This creature, armed with discernment about his or her medical needs and free choice of doctors and hospitals, will bring us to the paradise of low-cost medical care and uncompromisingly good health. Too bad that in the real world, empowered consumers and “consumer-driven healthcare,” the instrument through which they achieve these goals, are mythical.

The magnetic pull of these myths remains intense, even magical, among a certain category of reformer. The empowered consumer is a star of the latest conservative alternative to the Affordable Care Act, issued earlier this month by the American Enterprise Institute.

An empowered citizen-patient-consumer approach must be true to the Constitution and reflect a genuine federalist philosophy.

— American Enterprise Institute manifesto on healthcare reform

“U.S. healthcare would be far better, of higher quality, and less burdensome in terms of costs,” write the 10 conservative economists and healthcare analysts behind the AEI’s “Agenda for Reform,” “if citizens, in their roles as patients and consumers of health services ... were ultimately in charge of making the important decisions” about how to deliver services to themselves, that is: “the empowered citizen patients.”

This is certainly appealing. Nirvana always is. But is it practical? More to the point: Is there indisputable evidence that giving consumers more power over their healthcare choices, say by asking them to pay a larger share out-of-pocket for treatments, leads to better consumer choices and better health?

The answers are: not at this time, and no.

Let’s examine what we know about consumer-driven healthcare.

To begin with, true consumer-driven healthcare requires three things. These are: information about the prices charged by competing providers for given treatments; reliable data about the outcomes of medical options for treating any given condition or syndrome; and consumers who are inclined or able to base their healthcare decisions on the first two factors.

Comparative prices are hard to come by today even in intensely competitive healthcare markets such as big cities, much less in regions with only a small number of providers. Comparative outcomes? These often are hard even for trained clinicians to determine, and even then only after years of research; expecting patients to have this data at hand is chimerical. Finally, the vast majority of patient decisions may be utterly independent of cost and known outcome.

The key question really is how consumers actually respond to cost and price incentives. That’s because consumer-driven healthcare invariably relies on price signals to guide consumer behavior.

There seems to be little doubt that boosting deductibles and co-pays results in lower overall spending by consumers -- especially in the first year after higher deductibles were imposed. Researchers aren’t certain why this is.

Some speculate that consumers knowing that deductibles are going to soar next year cram a lot of treatments into this last low deductible year, the way some taxpayers will accelerate income into the last year before a tax hike. Healthcare expert Austin Frakt of Boston University guesses that consumers may try hard to save their money in the first year of the new regime by putting off treatments they think can be deferred, but that eventually they have to get that care.

One phenomenon that is well-documented is that the average consumer can’t distinguish well between essential and non-essential treatment. Those trying to keep from spending money out-of-pocket avoid both. They reduce their use of prescribed drugs. They skip preventive services.

Simply calling a patient a consumer doesn’t make buying healthcare like buying cars.

— Harvard economist Amitabh Chandra

What’s the result? It may well be higher spending overall in the long term. Syndromes that could be managed with drugs flare into serious conditions. Skipping an ounce of prevention means saddling the healthcare system with pounds of care. Do we want diabetics to put off treatment or medical consultations until they’re faced with vision, circulatory and kidney damage?

“Simply calling a patient a consumer doesn’t make buying healthcare like buying cars,” healthcare economist Amitabh Chandra of Harvard acknowledged recently in Forbes. “In healthcare, the consumer (i.e. the patient) is sick, tired, confused, distracted—they want their doctor or their insurer to help them manage the health-care that they need.”

Chandra acknowledged that it’s “tempting” to think that healthcare costs can be reduced “through a combination of “skin-in-the-game” health plans (a.k.a. high-deductible plans) and transparency tools to encourage shopping.” His own research suggests a much more complicated situation.

In a recent paper, Chandra and colleagues at UC Berkeley examined what happened at a large company that switched its employees from free medical care with no cost-sharing to a high-deductible plan. They found that employees actually did spend less after the switch, but no evidence that they were doing so by learning how to shop for the best-value care. Instead, they just used less of everything, including valuable services.

The consumers weren’t very adept at valuing these services or their needs, the researchers found. Even those who could be sure they would exceed their deductible by the end of the year tended to reduce their spending more while they still owed the deductible. That’s hardly a formula for better health, since they may be delaying needed services. Chandra and his colleagues write that high-deductible plans may achieve their spending reductions “in a blunt manner, where consumers reduce all types of care, including both valuable and wasteful care.”

Other indications are that high-deductible plans aim their benefits at the wrong consumers -- those who contribute very little to overall spending on healthcare. That’s because the vast bulk of spending is caused by a small proportion of consumers, while a huge proportion of consumers have only modest medical needs. Economists call this a “Pareto distribution,” and it’s illustrated by the graph above, which comes to us via economist Martin Gaynor.

As the graph shows, the top 1% of patients account for 20% of all spending, and the top 10% for 65% of all spending. The bottom 50%, however, account for only 3% of spending.

Here are the consequences, as insurance expert Richard Mayhew of Balloon-Juice.com observes: The low users may be good candidates for price incentives, since paying more out of pocket may dissuade them from procedures they really don’t need. But they account for a tiny proportion of all spending, so their incentives aren’t likely to save much overall. At the other end of the graph, however, are patients who need intensive coverage that’s likely to blow through any deductible or co-pay incentives that might exist. They’re chronically ill or victims of acute catastrophic illness or injury, and they’re not likely to pare their health demands to avoid hitting the deductible. They’re more likely to reach their out-of-pocket limits instead.

All the evidence for the efficacy of consumer-driven healthcare is at best equivocal, and at worst negative. What that implies is that the popularity of the consumer-driven model among conservatives is based not on empirical findings, but ideology.

Sure enough, the text of AEI’s reform paper gives this game away. “An empowered citizen-patient-consumer approach,” it reads, “must be true to the Constitution and reflect a genuine federalist philosophy.” It’s anti-federal government, though not anti-state government, as though wise healthcare policy can be prized out of the concept of states’ rights.

The authors also show what can be described only as an endearingly childlike faith in “advances in information technology and medical discovery,” which they say “hold the promise of transforming medical care in the United States in the coming years for the better.”

Two problems here. First, we’ve been hearing about the coming benefits of medical IT for decades now, and somehow the horizon seems to be continually receding. Second, the issue for millions of “citizens” isn’t whether medical advances will exist, but whether they’ll be accessible to people without access to fortunes. Consumer choice is meaningless if one’s choices are constrained by income, as is the case for many people without insurance.

The AEI folks also put great store in “market” forces resolving all ills, if they’re only allowed to work freely. (“Market” or “marketplace” appear almost as frequently in the AEI paper as “consumer.”) The problem is that free markets often don’t exist in healthcare, and when they do, they’re often asymmetrical. “There is no market within a half-day drive of the Major Academic Medical Center that can effectively treat certain types of pediatric cancers,” Mayhew observes, “so market forces don’t work.”

When you bring the AEI’s prescriptions down to Earth, they begin to look amazingly unambitious. Their real goal is to cut spending by government, especially the federal government. Almost everything else is a disguised attempt to hang more expense on patients who can’t afford it.

Mythologies can be comforting. When they’re used in healthcare to rationalize policies that haven’t been shown to work, they can also be dangerous.

Keep up to date with Michael Hiltzik. Follow @hiltzikm on Twitter, see his Facebook page, or email [email protected].

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.