GE shows how to make shareholders richer and retirees poorer

Great for shareholders, not so good for retirees: General Electric Chairman and CEO Jeffrey Immelt.

General Electric Co. has been patting itself on the back about its success in driving down the cost of its retiree benefits.

In its annual report for 2015, issued Feb. 26, the industrial giant reported that it slashed its total obligation for health and life insurance benefits to current and future retirees by $3.3 billion last year alone. That follows cuts by about $1.4 billion in previous years.

GE made a real promise to its salaried workers, and it had no reason to eliminate this benefit. ... This was gratuitous.

— Thomas Geoghegan, attorney for retired GE workers

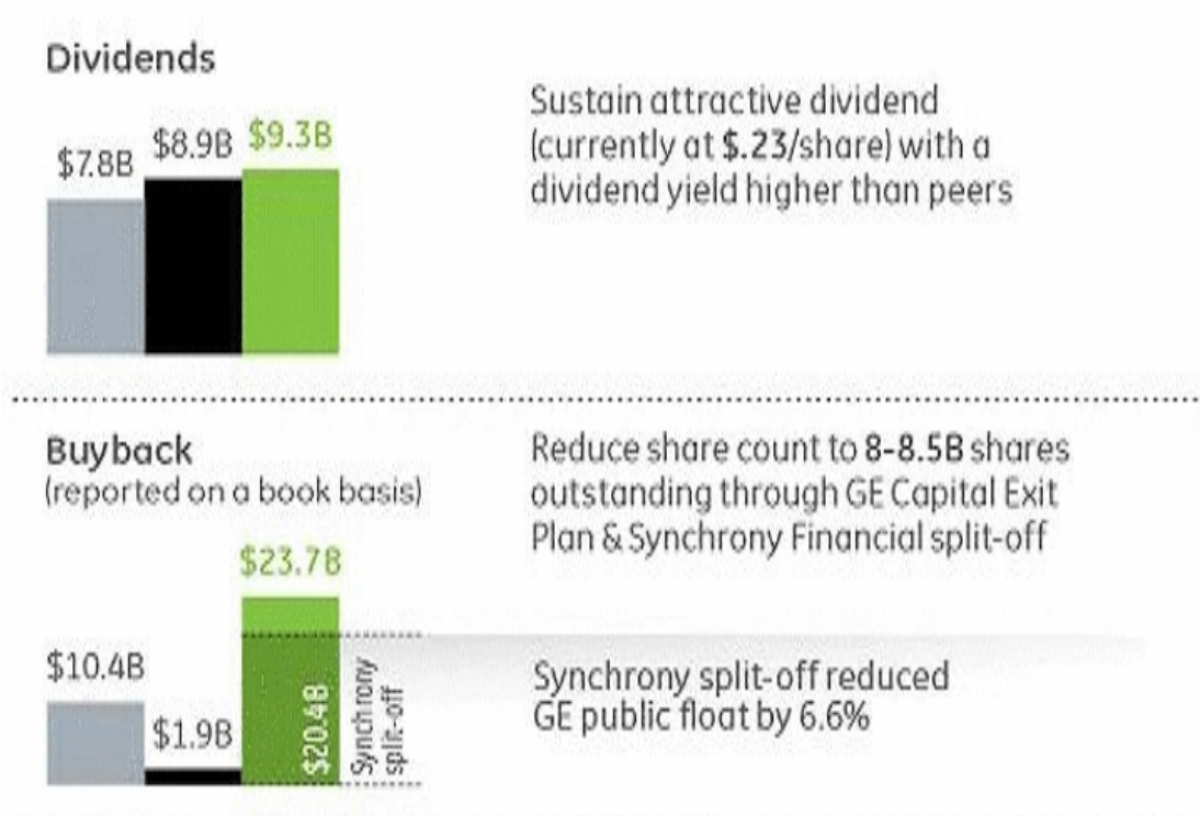

While GE was reducing its obligations to its long-term employees, it was also rewarding its shareholders. Over the past two years, they've received a raise of 13 cents per share in annual dividends, totaling $1.5 billion more per year. They also got a share buyback worth $3.3 billion last year alone, not including the value of GE's spinoff of Synchrony, its old GE Capital unit.

On the face of it, this is a textbook example of how a big corporation shifts resources from employees to shareholders, a major element in America's rising income inequality. Workers haven't been taking it lying down. The company's squeeze on retiree benefits already has generated two lawsuits — one from retired salaried workers that seeks class certification, and a second from GE labor unions that say the company's cutbacks violate labor contracts.

The first case, brought by retirees Evelyn Kauffman and Dennis Rocheleau in Milwaukee federal court, observes that as recently as 2012, the company committed itself in an employee handbook to maintaining its retiree healthcare plan "indefinitely." Two months after issuing that commitment to workers, the company announced that it would be ending the plan, which provided retirees with "Medigap" insurance to fill in the shortcomings of their Medicare plans.

The company did say that it reserved the right to change or terminate the benefit "at any time and for any reason," but the workers contend that it qualified its intentions by specifying that its decision could be "due to changes in federal law or state laws," among other reasons. That suggested that it wouldn't do so arbitrarily.

"GE made a real promise to its salaried workers and it had no reason to eliminate this benefit," the workers' lawyer, Thomas Geoghegan, told me. "Its costs weren't rising in any significant way, and GE wasn't in any financial trouble. This was gratuitous."

Federal Judge Lynn Adelman noticed the same thing, observing in December that GE didn't end the retiree benefits for any of the reasons it specified in the handbook. Those reasons all "involve a force majeure, something outside [GE's] control such as a change in the law," Adelman wrote. Rather, the company "appears to have terminated the Plans to save money."

Indeed, GE's profits and margins have been quite healthy over recent years, as is shown by the chart below. (The brief profit crash in early 2015 was the result of charges related to the Synchrony spinoff.)

Adelman rejected the workers' request for an injunction blocking the changes, but later cleared the case to move ahead on the claim that GE had misrepresented the plans' future. The plaintiffs are seeking class status to represent as many as 65,000 current and future retirees.

The second lawsuit, brought by nine GE unions in federal court in Cleveland, alleges that the company unilaterally altered retiree benefits that had been negotiated in the past and in which the retired workers had a vested right.

The company responds that its change, which shifted many retirees out of a subsidized Medigap plan and into a private exchange plan along with a flat $1,000 annual reimbursement, will be good for the workers because it gives them "the opportunity to choose coverage options tailored to their individual needs," instead of the previous "one-size-fits-all" benefits. It claims that its own consultants figure that 75% of eligible retires will "have the opportunity to save money under the new arrangement," though it doesn't specify how that might happen.

The company cites the same right to change or end the retiree benefits "at any time without limitation," whenever the applicable union contracts expired. The unions of course, contend that once a retiree benefit is earned under a contract, it's earned for good.

Other big companies no doubt will be keeping an eye on GE's fortunes in court, as it kept an eye on the spreading practice of corporations cutting benefits for their retired workers — its actions are "consistent with trends across the country," the company told the Ohio court.

The rest of us should keep an eye on the principles at issue here. General Electric worked out a trade. In exchange for cutting the benefits of its most loyal employees — those who stuck with the company long enough to retire with promised benefits — it has chosen to enrich its least loyal stakeholders: investors who will shed their shares in the blink of an eye, except for the fact that they're being bribed with higher dividends and lavish buybacks to stick around.

Which one of these groups is really responsible for GE's success over the years, and which really should be rewarded?

Keep up to date with Michael Hiltzik. Follow @hiltzikm on Twitter, see his Facebook page, or email [email protected].

MORE FROM MICHAEL HILTZIK

Tell me again how Obamacare is a 'disaster'

2016 is shaping up as the year of ransomware -- and the FBI isn't helping

Sanders got the gun makers' liability issue dead wrong (and got an attaboy from the NRA)

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.