Facebook’s user manipulation study: Why you should be very afraid

Facebook just doesn’t get it.

The company doesn’t get why people are pitching such a fit over the user-manipulation study it conducted in 2012, the details of which broke this weekend. It doesn’t get what this says about how it treats its users, and why it may, and should, discourage people from using its service. It doesn’t get that its researchers violated widely accepted standards for research on humans, or why that’s bad.

It’s tone-deaf about the implications. But that’s not new. This is just one more example of a reality of the Facebook experience that users keep forgetting. In a nutshell: As a Facebook user, you are not its customer. You are its raw material, which it exploits to make money typically by selling advertising ostensibly keyed to your likes and desires.

Indeed, this entire affair underscores the need for new laws and new regulations governing how companies like Facebook exploit their users--including through invasions of privacy and marketing of personal information to others.

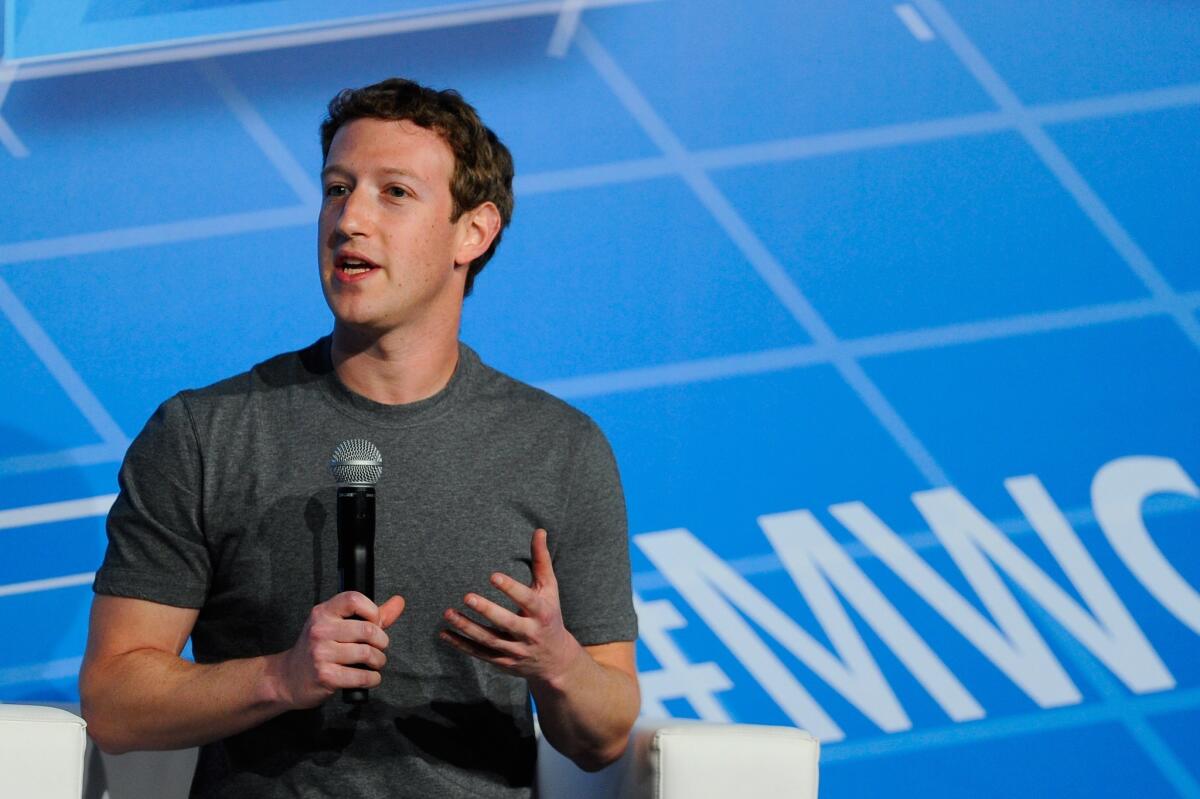

Facebook Chairman Mark Zuckerberg prattles endlessly about bringing the world together via social media. Bosh. As his website’s user, you’re nothing but a means to an end, and that end has nothing to do with your welfare.

What is now known is that for a week in January 2012, the company manipulated the news feeds on its site of some 700,000 unwitting users for a research study, which has now been published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Facebook reduced the purportedly positive feeds from some users’ “friends,” and limited the share of downer posts received by others. The goal was to determine how the differing tone of those feeds affected the subjects.

The researchers, who were one Facebook employee and two colleagues from Cornell University and UC San Francisco, found that the tenor of the news feeds indeed affected the subjects’ moods--those with fewer happy posts responded with more glumness in their own status updates, and those with fewer downcast items in their feed expressed, on the whole, more happiness. (The researchers describe the results in bloodlessly academic terms, but that’s how it worked out.)

Here’s how you should think about this entire affair, and why it might prompt you to reconsider using Facebook at all.

--Facebook violated fundamental guidelines of experimentation on human subjects. It’s true that as a private company, Facebook isn’t subject to the government’s Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects, known as the “Common Rule,” which applies to federally sponsored research.

That’s no excuse. Private companies performing such research customarily adhere to the rule; to the extent they don’t have to, that should be rectified by Congress.

The Common Rule requires “informed consent” from human test subjects. Facebook’s dodge is that the 689,003 subjects of its study implicitly consented to having their news feeds manipulated by agreeing to the company’s data use policy, the latest version of which comprises 9,123 words. Buried in that mess of verbiage is a warning that the company “may use the information we receive about you...for...data analysis, testing, research and service improvement.”

The Common Rule, however, defines “informed consent” as requiring--among many other things--that research subjects be told about the nature of the research and “any reasonably foreseeable risks or discomforts to the subject,” and that participation be voluntary and can be ended at any time. Plainly, Facebook’s data use policy doesn’t come close to “informed consent” as envisioned under the Common Rule. The researchers say the study’s subjects were randomly chosen. There’s no indication that any were informed in advance or afterward.

How this study got approved by the academic employers of two of the researchers remains mysterious. The editor of the published paper, Princeton’s Susan Fiske, told my colleague Matt Pearce in an email that she was “concerned about this ethical issue” in regard to subjects’ consent, but observed that Facebook “filters user news feeds all the time, per the user agreement. Thus, it fits everyday experiences for users, even if they do not often consider the nature of Facebook’s systematic interventions.”

She told the Atlantic, however, “I’m a little creeped out, too.”

--This is sadly typical of Facebook’s treatment of its user community. “This is bad, even for Facebook,” writes James Grimmelmann of the University of Maryland law school.

Back in 2012, I listed some of the ways Facebook manipulated users’ news feeds and account settings--not to the users’ benefit, but to offer a better experience to advertisers and gain more access to personal information. There were “sponsored stories,” items that turned up in your feed because advertisers had surreptitiously paid for them to be more prominent.

Then there was the time Facebook changed users’ email addresses to facebook.com addresses behind their backs, presumably to gain yet more access to users’ online activity. Periodically, the company would unilaterally change users’ privacy settings, customarily in the direction of less privacy.

After these actions were exposed, the company would apologize--pledging to be “better” about communicating the company’s activities. Each time, another thin layer of trust between user and company got chipped away.

--Facebook still doesn’t comprehend the scale of its violation. Facebook’s Adam D.I. Kramer, the lead author of the news feed study, has posted on his own Facebook page an explanation of what happened.

He says the firm did the study “because we care about the emotional impact of Facebook and the people that use our product.” (i.e., “Facebook, the caring company.”) He acknowledges that “we didn’t clearly state our motivations in the paper,” but maintains that the disruption in the subjects’ lives was “minimal.”

He concludes, “In hindsight, the research benefits of the paper may not have justified all of this anxiety.”

Facebook itself told The Times, “We carefully consider what research we do and have a strong internal review process.” In a statement to Forbes, the company treated the affair as a privacy issue, and claimed blamelessness on that score. “None of the data used was associated with a specific person’s Facebook account, it said. “There is no unnecessary collection of people’s data in connection with these research initiatives.”

Facebook’s behavior in this case is all of a piece with the shockingly casual way that high-tech consumer companies have been appropriating users’ personal data. They’ve been getting away with murder for far too long. Their usual practice is to stretch the bounds of fair or commercial use until they get caught, and then sheepishly apologize for their error and promise not to do it again.

Facebook is far from the only offender. Every company in the tech business hoovering up people’s private information knows exactly what it’s up to. The industry hasn’t shown the maturity to treat users’ information as the users’ property, not the company’s, and the Zuckerberg retreat--”forgive me, I didn’t realize”--no longer is an adequate excuse.

Congress should lay down guidelines, enforceably. In the meantime, users of serially offending services like Facebook need to think about whether to continue using them, if that means giving up your personal data, and part of your soul.

Keep up to date with The Economy Hub by following @hiltzikm.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.