Column: Trump’s assault on Obamacare was much more damaging than previously thought

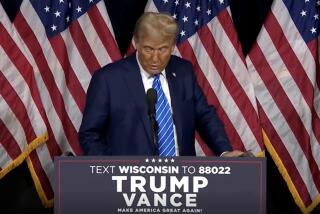

Donald Trump opened his presidency in January 2017 with a series of salvos aimed at the Affordable Care Act, the signal achievement of his predecessor’s administration.

It has long been assumed that these attacks reduced signups during the crucial final weeks of open enrollment for 2018 insurance policies. New data parsed by two experts at Duke University and the University of North Carolina show how steep the reduction was. Spoiler: It was huge, and devastating.

That’s because the drop-off was concentrated among the healthiest group of potential enrollees. They’re the ones who often wait until the last minute to sign up, and therefore were still pondering their options on Inauguration Day, Jan. 20, and up to the enrollment deadline of Jan. 31.

The lack of political support for the law by the incoming administration seemingly had an immediate and significant downward effect on Marketplace enrollment.

— Anderson & Shafer

“It’s a flip of a coin whether they’re going to sign up at all,” David Anderson of Duke, the paper’s lead author, told me. Because they’re healthier and thus cheaper to cover, losing them from the overall insurance pool means higher premiums for everyone else.

The very first executive order of Trump’s term, issued on Jan. 20, signaled that enforcement of the ACA’s individual mandate effectively would cease. The order encouraged the Department of Health and Human Services to “waive, defer, grant exemptions from, or delay the implementation” of any parts of the ACA if it found they would “impose a fiscal burden” on individuals or states. Trump pledged to repeal the ACA, which he assailed as a failure and a “disaster.” He canceled TV and radio advertising scheduled for the end of January urging people to enroll.

All this signaled that the atmosphere surrounding the law had dramatically changed. The general effect was noticeable, with enrollments for 2017 via the federal government’s healthcare.gov website, which handled signups for more than 30 states, falling by about 400,000, or more than 4%, from 2016.

The paper by Anderson and Paul Shafer of UNC, which is published in the peer-reviewed Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law, focuses on the final two weeks of open enrollment for 2017. They found that enrollment fell by a stunning 30% in that period compared to the same period a year earlier under President Obama, when outreach, advertising and hands-on enrollment assistance was robust. That’s enough to account for at least a percentage point or two in increased premiums.

“The lack of political support for the law by the incoming administration seemingly had an immediate and significant downward effect on Marketplace enrollment nationwide,” Anderson and Shafer write.

“Messaging matters,” Anderson says, “especially for the least attached chunk of the population.”

It’s important to consider the difference between the late and early enrollees. Most people have a decent sense of their likely medical costs for the coming year, barring a surprise injury or diagnoses.

As Anderson observed in a blog post, “Folks who know that they are likely to incur ... $100,000 or more in claims are very likely to sign up for health insurance that is community rated, guarantee issued and heavily subsidized no matter what the messaging regime is…. They will crawl through glass for coverage.”

These are people with chronic diseases or ongoing, expensive disease treatments; those eligible for an ACA plan probably signed up even before election day on Nov. 8, 2016. (Open enrollment started on Nov. 1.) They wouldn’t wait until the last minute, in part because enrollments after mid-January would be effective only on March 1.

“Folks who think it is likely that they will be in the bottom 50% of the US healthcare spending distribution ($0-$1,000 in total spend) tend to enroll late,” Anderson blogged. “They are the ones who need strong encouragement to go onto the Exchanges and buy.”

They’re also strongly needed by the insurance pool. According to Matthew Fiedler of the Brookings Institution, the late enrollees tend to be 15% to 27% cheaper to cover than the pool as a whole. In effect, they’re subsidizing the general population. This may look unfair, superficially, but of course they’ll benefit if they get surprised by an injury or illness, and in time they’ll age into the population that tends to incur higher costs.

Trump, as is well known, has followed his initial assaults on the ACA with consistent sabotage. He cut outreach, advertising and enrollment assistance to the bone for 2018 and later kept pressure on congressional Republicans to repeal the law. He’s moved to widen access to junk insurance plans that the ACA aimed to eradicate, with the fatheaded claim that because they’re cheaper they must be better for consumers. As recently as this weekend, he claimed to have a replacement law in the works.

Not all these steps have worked out as Trump expected. His cancellation of reimbursements to insurers for premium and deductible subsidies they’re required to offer the poorest enrollees led to an increase in federal premium subsidies generally, which actually made most ACA plans more affordable for subsidized consumers. And the steady drumbeat of threats against Obamacare has actually made it more popular among the general public, which has become fully alive to how Republican repeal would jeopardize their health insurance coverage.

There may be more arrows in Trump’s anti-ACA quiver. Republicans are seemingly aware that this isn’t a good look for them, as the Democrats have made protecting Americans’ health coverage a central plank in their platform, and used it to rout the GOP in 2018 House races.

Keep up to date with Michael Hiltzik. Follow @hiltzikm on Twitter, see his Facebook page, or email [email protected].

Return to Michael Hiltzik’s blog.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.