Time’s debt scare cover story is a journalistic — and economic — train wreck

Time Magazine is mightily, and inordinately, proud of its cover story this week, proclaimed by a blood-red illustration announcing to every reader that he or she owes $42,998.12 as a share of the national debt.

It's hard to find a reason for the pride. The article, titled "Make America Solvent Again," is poorly reasoned, simplistic, self-contradictory and baldly ideological. It gets history wrong and lionizes economic policies that were discredited decades ago. Its few nuggets of truth and rationality are swamped by a torrent of wrong.

What's especially curious about this episode is that Time chose to turn its cover over to an outsider. The author is James Grant, who as founder (in 1983) and editor of the independent newsletter Grant's Interest Rate Observer has long been one of our most skeptical chroniclers of business and economic trends.

If you are a subscriber, you are holding something of a collector's item.

— --Time Editor Nancy Gibbs, telling a whopper

Grant's contrarian writing has been hailed for its perceptiveness and wit. He earned every ounce of the lifetime recognition he received last year from the Gerald Loeb Awards (think of them as the Pulitzers for business journalists). The Time cover story may ruin his reputation. It won't surprise Grant's followers that he's a fan of the gold standard and a critic of the Federal Reserve; it's the weakness of his arguments that may come as a shock.

In any event, Time offers no clue that Grant approaches the issue of the national debt not as a neutral observer but from a specific philosophical position. "As we mark tax day," writes Time Editor Nancy Gibbs blandly in a letter to readers introducing the cover essay, "it’s appropriate to remember, as Grant points out, that the $42,998.12 share of federal debt for each and every American ultimately represents a form of deferred tax that must one day be paid."

The cover story, for the Time issue dated April 25, already is taking fire. At Slate, Jordan Weissmann calls it "unforgivably idiotic ... a Dorito in stat form." Matt O'Brien of the Washington Post tweets that its core claim that the U.S. is effectively insolvent "perniciously stupid." Economist Dean Baker labels the scare headline "unbelievably silly. ... This has nothing to do with people’s future living standards, nothing to do with the ability of the government to pay back its debts. It’s basically zero information.”

Let's just pick apart a few of Grant's points, to serve as windows into what he's really saying and where we think he goes wrong.

Debt: "It is better not to incur it." Grant starts right in with a bizarre assertion: "This much I have learned about debt after 40 years of writing and study: It is better not to incur it. Once it is incurred, it is better to pay it off."

Does Grant really believe this? Plainly not, for a few paragraphs later, he writes, "Debt per se is neither good nor bad." That statement is the true one.

The fact is that there are many circumstances, in business and personal finance, in which taking on debt is the right choice. As a capital-raising device, debt is almost always cheaper than equity: Debt typically represents a fixed charge against cash flow, but equity requires a business to give up a portion of its profits forever. If you're starting up and need financing to, say, build inventory, buy equipment and hire staff, you normally don't want to give away a portion of the company to fulfill a short-term need. Interest on debt also is tax-deductible. As for paying it off, that depends. If the interest rate on a loan is likely to be lower than the gains that can be earned by investing the principle instead of returning it — investing it in the business, say — it makes no sense to give up that capital rather than carry the cost of it.

Grant could have found somewhere in his 2,100-word essay to make that point. But he didn't. The closest he came was to fret that the low interest rate on federal debt today is dangerous because it encourages more borrowing. Yet from a policy standpoint the truth is just the opposite: This is exactly the right time for the government to take on more debt because it's cheap to borrow to build and repair infrastructure that will yield far more in economic growth than the average 1.8% a year it costs to finance it.

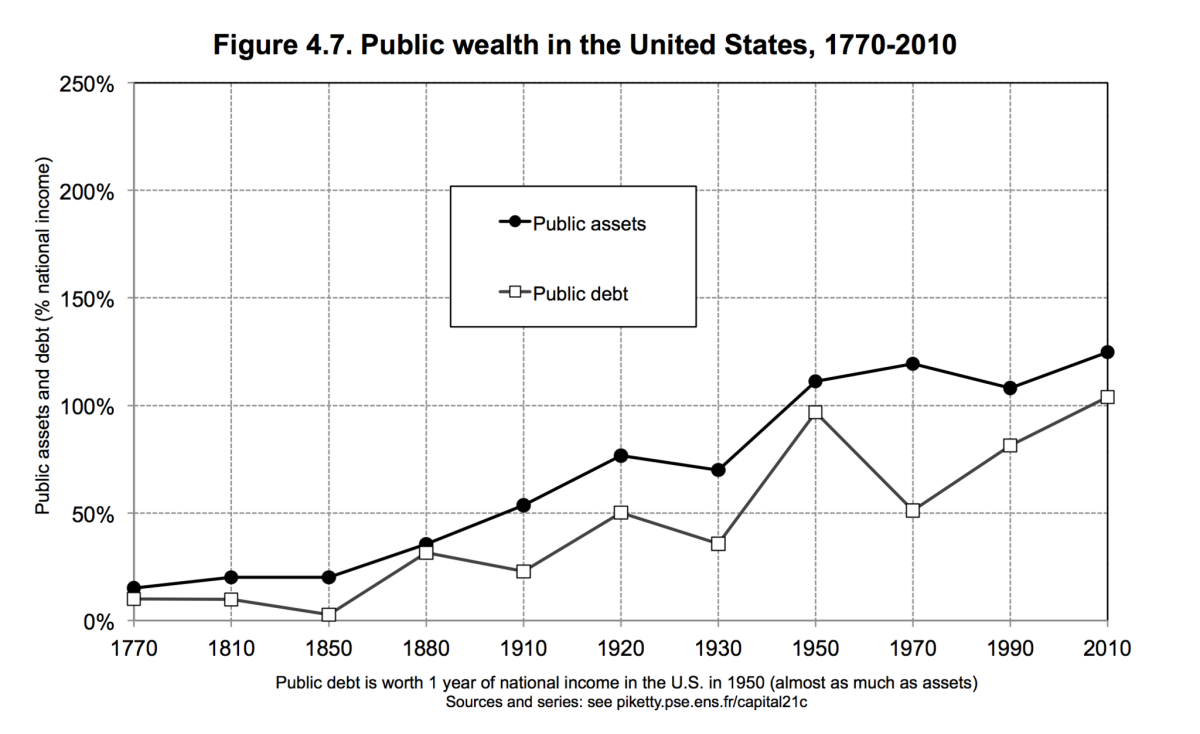

"We owe more than we can easily repay." This is the crux of Grant's argument that the government is effectively insolvent. Grant's technique is the familiar one of examining only one side of the ledger. Yes, the government has liabilities, but it also has assets. Put them together, and the United States is massively in the black, as economist Thomas Piketty documented in his book "Capital in the Twenty-First Century."

What does the government own? Start with energy reserves. The Institute for Energy Resources has estimated these to be worth $128 trillion, enough to pay off almost all of the $13.9 trillion federal debt (as reckoned by Grant) all by themselves. Then there's its vast inventory of buildings and land and the value of monopolies it has the power to hand out, for a fee, in patents, copyrights and other rent. Let's not overlook, as Grant does, that debt-financed expenditures create new value. Sometimes they build schools or office buildings; sometimes they pay for national defense, whether in ships or aircraft or in the sense of security that lubricates American commerce. It's a conservative debating device to assign these assets a value of zero, but a dishonest one.

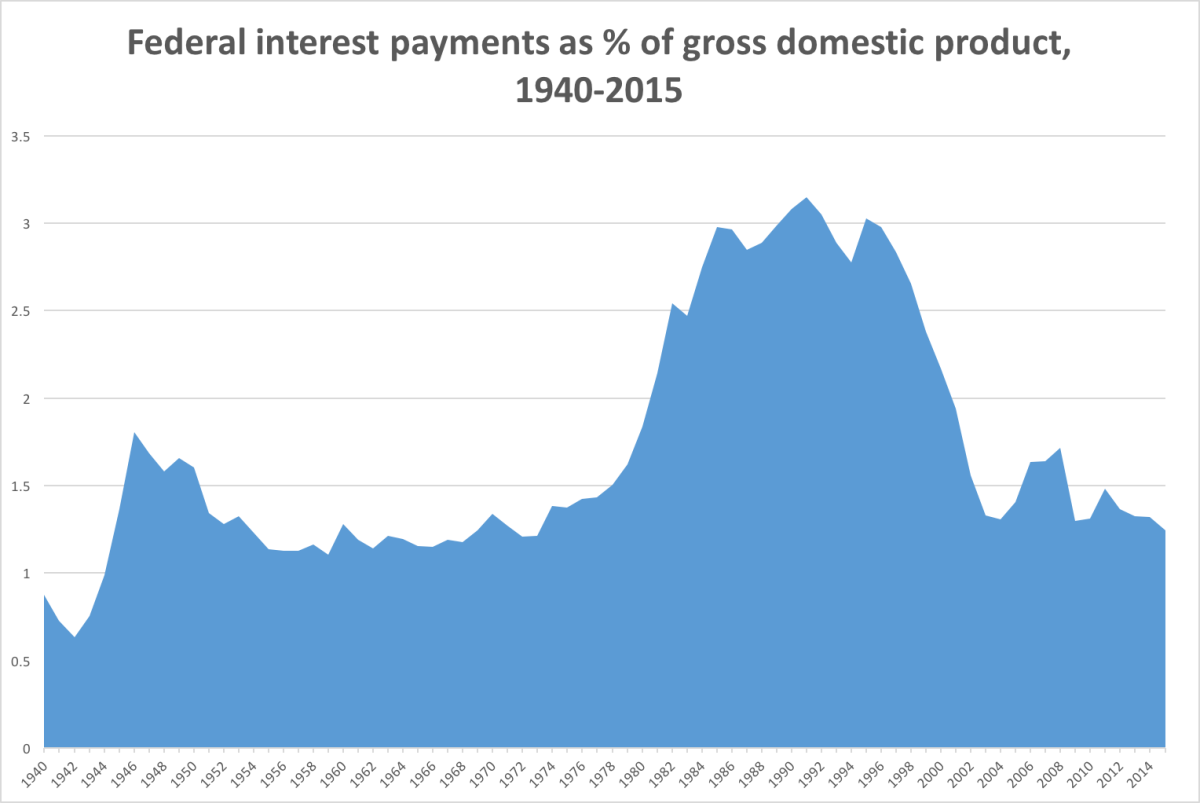

As for the assertion that the per-capita debt service equally overburdens every American (or every subscriber to Time), that's merely a scare tactic. The principal can be perpetually rolled over, and the interest charges on their own have been declining as a percentage of gross domestic product; they currently represent the lowest share of the economy in more than 50 years.

Grant argues that the low interest rates we're paying today on our debt is leading us into a mug's game, for the day will surely come when rates rise. "At 4.8%, the rate prevailing as recently as 2007, the government would pay more in interest expense — $654 billion — than it does for national defense," he writes. This is so, but the signal coming from what Grant has termed "Mr. Market" doesn't point that way. What could drive rates higher? One thing might be a surge in economic growth, but that would mean an expansion in GDP, which would tend to maintain the interest/GDP relationship.

Grant warns that the merry-go-round of low rates "will eventually stop." But he won't posit when. "I don't know the date," he writes, "but I believe I know the reason. It will stop when the world loses confidence in the dollars we owe. ... One can assume that creditors trust the currency in which they expect to be repaid. I wonder why, and for how much longer." He doesn't say what could bring about America's moment of truth, or acknowledge that for something approaching a century, world crises and economic slumps have tended to make the U.S. economy, and therefore faith in the dollar, stronger.

Grant is probably correct that at some point the merry-go-round will stop. But saying that we should make drastic changes in policy today because of an event that may happen in the indeterminate future isn't very valuable as a prescription, especially since it imposes real costs on some members of the public, such as the working class, in exchange for a conjectural safeguard for others, namely bondholders. Grant glosses over this imbalance by suggesting that every American man, woman and child today bears an equal burden of the cost, but that's manifestly untrue; to the extent it's a burden, it's arguably a greater burden on those who collect the most income and pay the most income tax. Grant's suggestions would shift the burden of the debt lower on the income scale.

The answer: the gold standard? Grant's devotion to gold has been widely remarked, and reappears here. Do the editors of Time understand that they ceded their cover to a plea to return to retrograde economic theory, or the consequences of such a policy?

The gold standard has been enjoying something of a vogue in Republican presidential politics these days, as I documented here. But its appeal is limited, even among conservatives. Wrote James Pethokoukis, a commentator for the American Enterprise Institute, "I sure hope they’re not serious and this is just campaign season silliness." Grant himself acknowledges that the gold standard works, until it doesn't work, as happened in "depression in the 1930s and war in the 1940s." He might have added that by tying the hands of policymakers, the gold standard probably would have consigned the developed world to years more of economic disaster after 2008.

Of the spending encouraged by the lack of a leash of gold, Grant writes, "the proliferating dollars facilitate heavy borrowing. Ultra-low interest rates mask the cost." Yes, but "ultra-low interest rates" are the cost. This is like saying that milk and eggs only look cheap at the supermarket because we're misled by their low prices.

The flat tax: "An identical low rate on most incomes." The flat tax is a conservative Republican shibboleth, and it's distressing to see a "wise economic analyst" like Grant buying into the obvious fraud. The late Herbert Stein, the chief economist for the Nixon administration and an uncommonly wise conservative, put the myth of the flat tax in the grave in a Wall Street Journal op-ed in 1996, when the concept was being shot around by presidential contenders like Steve Forbes and Jack Kemp (as it is today by Ted Cruz, et. al.). Observing that all such proposals involve exempting the first few thousands of income from tax to protect low-income people, he observed that there's actually no such thing as "an identical rate on most incomes."

Of the plans circulating in the 1990s, Stein wrote, "People with incomes below the personal exemption would pay zero tax, people with incomes twice the exemption would pay 10% of their total income, people with 10 times the exemption would pay 18% of their total income, and people with 100 times the exemption would pay 19.8%." That's a progressive system, not a flat tax, he observed, and the only point subject to debate was how much progressivity was proper. He offered a rule "derived from 60 years of observation. ... Whatever is the existing degree of progression, people who pay the top rate will think it is too much."

Social Security: "You don't miss the income that you never get to touch." Grant asks his readers to examine their paychecks and "notice the dollars withheld for Medicare, Social Security, and so forth." This is that same conservative trick of pretending that the withheld funds don't buy anything.

Grant, like many other conservatives, invokes "entitlement" as a curse word. In truth, Social Security and Medicare are "entitlements" because their beneficiaries paid for them out of their paychecks.

Grant repeats the familiar critique that "there are no accounts earmarked for you, the citizen, who so faithfully 'contributed' your payroll taxes."

This is extremely misleading. Social Security benefits are set by law, and it would take an act of Congress to eliminate them. If Grant thinks our federal legislators are up to that challenge, then why does he also write that "politicians ... ratchet up the benefits they promise to retirees (a fact that state and federal pensioners are encouraged to remember on Election Day.)"

Like many of Grant's darts, this one doesn't survive careful scrutiny. Congress hasn't expanded Social Security benefits since 1960 (although it should). Benefits are subject to an annual cost-of-living increase, but the increase for 2016 — an election year, in case you haven't noticed — is zero.

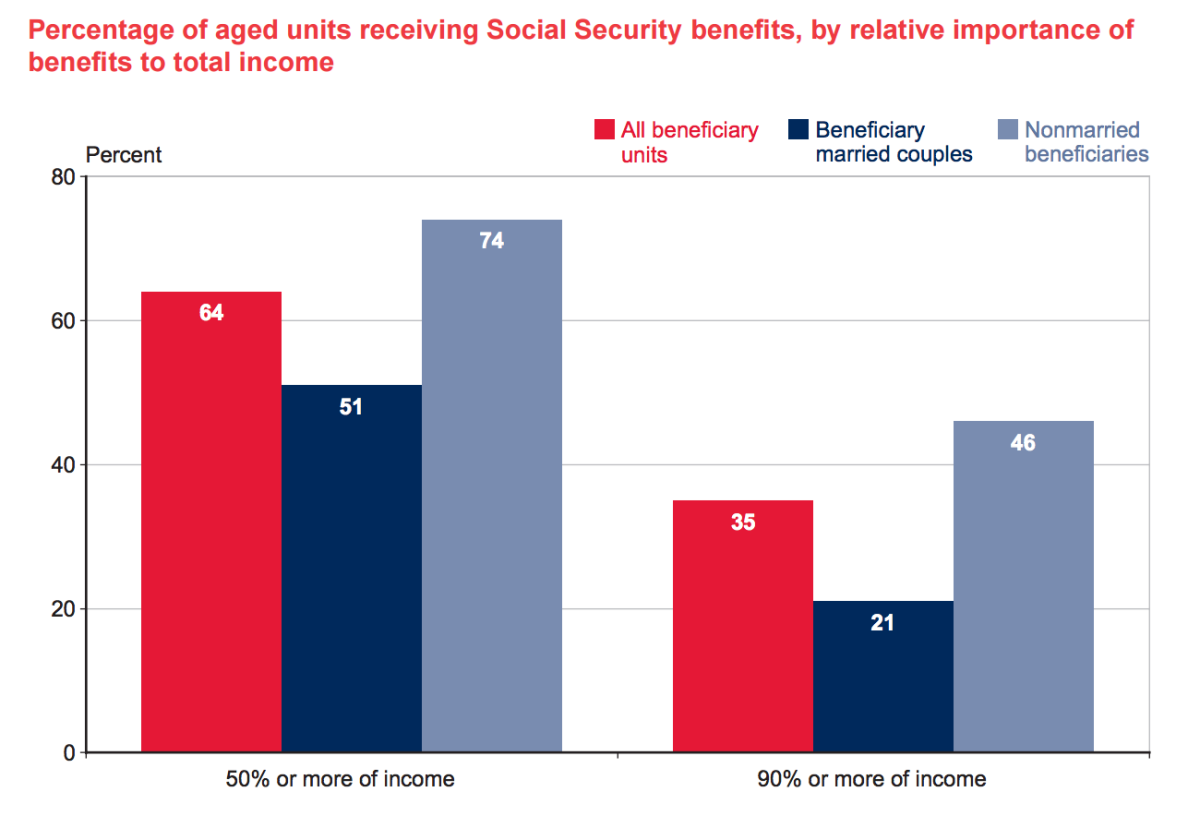

Ask the retirees on Social Security or those treated under Medicare if the money they contributed went for nothing. It's a safe bet that the vast majority would agree that they're fortunate to receive their monthly Social Security check. (Social Security accounts for more than 90% of the income of about a third of all retired individuals or couples, and more than half the income for two-thirds of those in retirement.) Most surely would express relief at having their healthcare needs covered by Medicare. These programs were enacted precisely because of a tide of poverty and poor health afflicting America's seniors.

In her letter to readers, Gibbs gives the impression that she and her magazine know nothing about Grant and less about economic policy: He's a "wise economic analyst" writing with "refreshing candor and clarity." It's hard to avoid the conclusion that Time's editors were snookered into running an ideological screed under the misimpression that it was an act of reportage. That they chose an openly alarmist and factually inaccurate cover line to advertise it only magnifies the blunder.

That's not to say there's no place in the public debate for Grant's argument, just that he represents a specific economic viewpoint. Over the years, he's been a cogent and entertaining spokesman for that viewpoint. But as policy, it's very 1920s. Then again, Time Magazine was founded in 1923. Who would have guessed that the magazine was still living in that era?

Keep up to date with Michael Hiltzik. Follow @hiltzikm on Twitter, see his Facebook page, or email [email protected].

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.