Does Andy Puzder really want to replace his Carl’s Jr. workers with robots? No, but...

Andrew F. Puzder, chief executive of CKE Restaurants Holdings -- that's the company that owns the Carl's Jr. and Hardee's restaurant chains -- has been taking a lot of heat for an interview he gave earlier this month to Business Insider, in which he was quoted singing the praises of restaurant automation.

According to the quote, Puzder feels that machines are much easier to deal with than humans. "They're always polite, they always upsell, they never take a vacation, they never show up late, there's never a slip-and-fall, or an age, sex, or race discrimination case." (Technical note: "upselling" means steering customers toward products with higher price tags.)

[Machines are] always polite, they always upsell, they never take a vacation, they never show up late, there's never a slip-and-fall, or an age, sex, or race discrimination case.

— CKE Restaurants Chief Executive Andrew Puzder, as quoted in Business Insider

The business press picked up this ball and ran with it. Within days, there were headlines, like this one in Fortune, declaring: "This Fast Food CEO Wants to Replace Workers With Robots," etc., etc. We would have joined in the fun but chose to call Puzder first, to see if he wished to amplify. This led to an extended interview late last week in which Puzder, 65, freely and cordially discussed his views not only on automation, but the minimum wage, the Affordable Care Act, and other issues relevant to the low-income economy.

As anyone can tell from his regular op-eds in the Wall Street Journal and elsewhere, Puzder's views are unapologetically conservative. But they also reflect the worldview of a veteran business executive whose workforce is heavily tilted toward the low-income end of the employment scale -- actually that's mostly the workforce of CKE's franchisees, who own and operate 92% of its restaurants. CKE, which traces its history to the first Anaheim restaurant Carl Karcher opened in 1945 and was taken private in 2010, is in the process of moving its headquarters from Carpinteria to Nashville.

As is evident from their raunchy TV campaigns, Carl's Jr. and Hardee's (the first is essentially CKE's Western U.S. and Hardee's its Eastern brand) target what might be termed the hairy-chested, beer-drinking young men's demographic. That's also shown by their hamburger menu choices, which often weigh in at 1,000-plus calories.

But it's the low-income workforce we're concerned with here; a segment most often impacted by social initiatives such as wage and benefit regulations. Puzder sees his company as providing a stepping stone for entry-level workers toward managerial careers, whether at CKE or elsewhere. "Some move on to other jobs and challenges equipped with the experience you can only get from a paying job," he told a Senate committee last year. "There's nothing more fulfilling than seeing new and unskilled employees work their way up to managing a restaurant."

CKE offers tuition reimbursements for job and career-related education and training to full-time employees who have been with the company for a year, with a lifetime maximum of $20,000. It also offers health plans for managers or those working 30 hours a week or more. But those benefits are for corporate employees, not for those of its franchisees, who hire and supervise the vast majority of workers in CKE restaurants. That's a major issue in the fast-food space, as the National Labor Relations Board, in a case involving McDonald's, is pushing hard to designate the big franchisor companies joint employers of workers hired by their franchisees.

Puzder's views of the fast-food economy are more nuanced than one might expect from reading his Wall Street Journal editorials alone, and they're worth hearing. We've broken them up by theme, beginning with the issue that got the conversation going.

Technology and automation: No, Puzder doesn't intend to "take humans out of the fast food equation," as Fortune had it. His remark about machines being so pliable was part of a longer exchange about the upsides and downsides of automation, the second part of which didn't get reported.

So he followed up with an op-ed in the Journal last week putting it on the record: "Customer service is still very important and, for now, having access to a person is important to assure smooth experiences for everyone. Increased automation also makes it more difficult to build a company culture. There are maintenance costs, and the business has to hire IT professionals to service the technology. The technology can malfunction, spoiling a patron’s visit."

"I never even mentioned robots," he told me, a bit chagrined. His point, he said, is that government mandates impose costs that "make automation a more viable option for business." But "we could never take out all the front-line employees" at CKE restaurants. At Carl's Jr. and Hardee's "you have to have people behind the counter because [customers] are used to that and people are more comfortable with it." He might consider, however, equipping restaurants near college campuses or other youth-oriented neighborhoods with touch-screens, because he believes that millennials are more comfortable with automated ordering.

But he thinks more automation is the wave of the future. "You can't stop the process," he said; it's the cost of those mandates that are forcing it to happen too fast.

Minimum wage: Our conversation took place the day before Gov. Jerry Brown and labor unions announced a deal to enact a $15 minimum wage in California through 2022, but judging from our talk, Puzder would think this is a bad move. He says he's not against a minimum wage higher than today's federal level of $7.25 an hour, or even to indexing the minimum to inflation. But he believes a jump to $15, even over a few years, inevitably will cost many low-wage workers their jobs. He's not alone in feeling uneasy about the magnitude of such a change, as we observed in our analysis of the state initiative here.

We asked about the recent remarks of McDonald's executives, expressing satisfaction with the results of their initiative to raise the wages of restaurant employees above the prevailing legal minimums. Employee turnover is down, customer satisfaction is up, and hiring is up, too. “So far we’re pleased with it," McDonald’s U.S. president Mike Andres told analysts at a recent meeting. "It was a significant investment, obviously, but it’s working well.”

Puzder observes, "They're not talking about $15 or $12 an hour, the kind of dramatic increases that are being bandied about in the political process right now." CKE's average wage, he says, is a bit over $10 an hour, "so we're not talking about everybody in the restaurant working for $7.25." (In California, the minimum wage is now $10.) "But we're talking about entry-level jobs. Are people going to want to hire entry-level employees for these very high minimums, which come with Obamacare, which come with mandatory sick leave, or other benefits which the government imposes on business for these individuals? Are you going to be able to keep minimum wage entry-level job positions open for individuals?"

At CKE, he says, "people don't make minimum wage for a very long period of time. If you're going to stay and you show you have value, then your wage is going to go up. ... I don't think anybody plans to have a workforce of minimum-wage employees. That's just not the way it works." He adds, "there's nothing wrong with rational increases in the minimum wage that don't kill jobs." Adjusting the minimum to inflation, he said, at least would avoid the abrupt jumps in costs that occur when lawmakers try to rectify years of wage erosion all at once.

"I started out scooping ice cream at Baskin-Robbins at a dollar an hour," he said. "I learned a lot about inventory and customer service ... but there's no way in the world that scooping ice cream is worth $15 an hour, and no one ever intended it would ever be something that a person could support a family on. ... Those jobs just don't produce that kind of value like a construction job or a manufacturing job does." (Puzder didn't say, but judging from his age he probably was scooping ice cream in the mid- to late 1960s, when one dollar was worth what about $7.50 would be today.)

Obamacare: The Affordable Care Act is one of the most frequent topics of Puzder's writings. CKE long has offered ACA-compliant health plans to managers or those who worked 30 hours a week or more, and "minimed" plans to others. Today it still offers indemnity plans, which provide discounts for certain medical services, to workers otherwise ineligible for more comprehensive coverage. Puzder says the take-up rate on those plans is very low, which he interprets as a sign that the vast majority of young people don't want the coverage and would rather pay the individual penalty than pay for insurance.

The difference is narrowing, though -- the penalty was $325 per person last year, but $695 this year. And many CKE employees may not be taking up company coverage because it's cheaper to buy on the ACA exchanges, especially for people eligible for tax subsidies.

Puzder's brief against Obamacare is familiar in conservative circles: Costs and deductibles are rising, insurers are having trouble making money in the individual market. He maintains that the program is giving small employers an incentive to lay off workers to avoid the insurance mandate, and that includes CKE franchisees. "The government is traditionally not very good at managing these types of programs," he told me. "The incentives of Obamacare are not set up in a way that makes economic sense. Obamacare is surviving based on increased government funding and increased taxpayer funding."

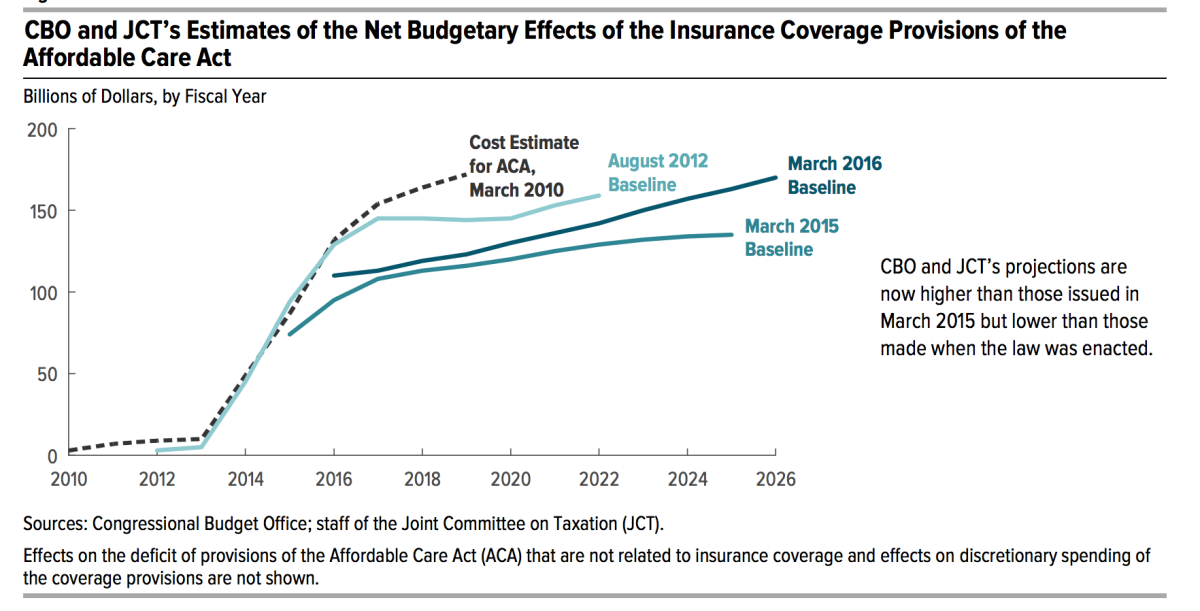

Some of Puzder's points merit challenging. The rise in insurance costs and deductibles predated the ACA by many years, and in many respects have moderated since. While major insurers have said they're not yet making money on individual ACA plans, most chalk that up to the growing pains of a market that didn't exist in its present form three years ago, and say they're committed to staying in. Yes, Obamacare is dependent on government funding -- that's what makes insurance affordable for low- and middle-income Americans, and allows states to provide coverage via Medicaid. But that was part of the design from the inception. And while costs are expected to rise as more Americans become insured and file for premium subsidies, estimates of these costs have been recalibrated down: The Congressional Budget Office this month projected that coverage-related costs to the federal government would come to $466 billion in 2016 through 2019. That's a bit higher than its projection a year ago, but 25% below its original projection in 2010. Among the reasons are that the growth in healthcare costs has been slowing, and fewer Americans than originally expected are leaving employer health plans to buy insurance on ACA exchanges.

As for whether Obamacare is prompting small businesses to lay off workers or shrink their hours, it's possible that the world looks different to those on the firing line, like Puzder, than to those taking a macro view. But as we've reported, there is simply no evidence of an increase in part-time workers since the law went into effect, except those able to go part-time voluntarily because that no longer means giving up health coverage.

Puzder found some of his evidence for the dire impacts of the ACA in job statistics. He cites employment figures from the Bureau of Labor Statistic showing that since December 2007, which he identifies as the beginning of the recession, the economy has added a net 4.8 million jobs, of which 3.1 million, or 65% were part-time.

But that time frame includes two years in which the recession was still killing jobs. If one starts at December 2009, when that trend bottomed out, the picture is much different: Employment has risen by 13.1 million, of which 374,000 jobs were part-time -- 3%. So Puzder has included two years in which overall employment fell sharply before recovering, and full-timers got shifted to part-time work. But that's changed since 2009 (and since the implementation of Obamacare after 2010).

Puzder knows the American workplace is changing, and he feels strongly that his company occupies the sector where those changes are likely to bite first and hardest. That's why that sector is the target of some of the most aggressive federal efforts to moderate the social impacts of market-driven changes; Puzder argues that many such efforts are counterproductive.

"It sounds good to say we're going to give everybody a raise," he told me, "but I don't think people think about the implications of that. If the business community doesn't speak up, the politicians who garner votes by making those claims and passing this legislation are just going to keep saying things that just aren't accurate. It's important to speak up, so I did."

Keep up to date with Michael Hiltzik. Follow @hiltzikm on Twitter, see his Facebook page, or email [email protected].