Column: The Theranos Affair: When Silicon Valley hype outpaces reality

Theranos Inc. is a Silicon Valley start-up that over the past year had been acquiring immense attention, and a valuation of billions of dollars, for a blood-testing technology that was poised to revolutionize the field — cheap, easy, informative blood tests obtainable on demand at your corner pharmacy.

That changed last week, when articles in the Wall Street Journal reported that the firm has struggled to show that its technology works, and suggested that it may have been misleading the public, and possibly government regulators, about the effectiveness and accuracy of its technology. Now it’s showing what happens when Silicon Valley hype outpaces reality.

Theranos called the Journal’s findings “factually and scientifically erroneous and grounded in baseless assertions by inexperienced and disgruntled former employees and industry incumbents.”

SIGN UP for the free California Inc. business newsletter >>

Silicon Valley is often lauded as an ecosystem that fosters high-tech growth through the interaction of venture capital, technological know-how, and yes, PR. Theranos points to the downside of the same phenomenon, in which interest by venture investors feeds on itself, and the publicity machine may gloss over how much work needs to be done to actually bring a “revolutionary” breakthrough to fruition.

A common adage is that venture capital is expensive money, but smart money; by contrast, stock market capital is cheap money but dumb money. The idea is that stock investors throw money at you but expect unrealistic results; venture investors demand big chunks of your company, but their wisdom and experience help you grow.

Theranos may demonstrate the flaws in this generalization. If the rap on the firm’s technology is even partly true, then its $9-billion venture valuation reflects investor’s hopes and fantasies rather than the technical knowledge and rigorous financial assessment for which the venture community prides itself.

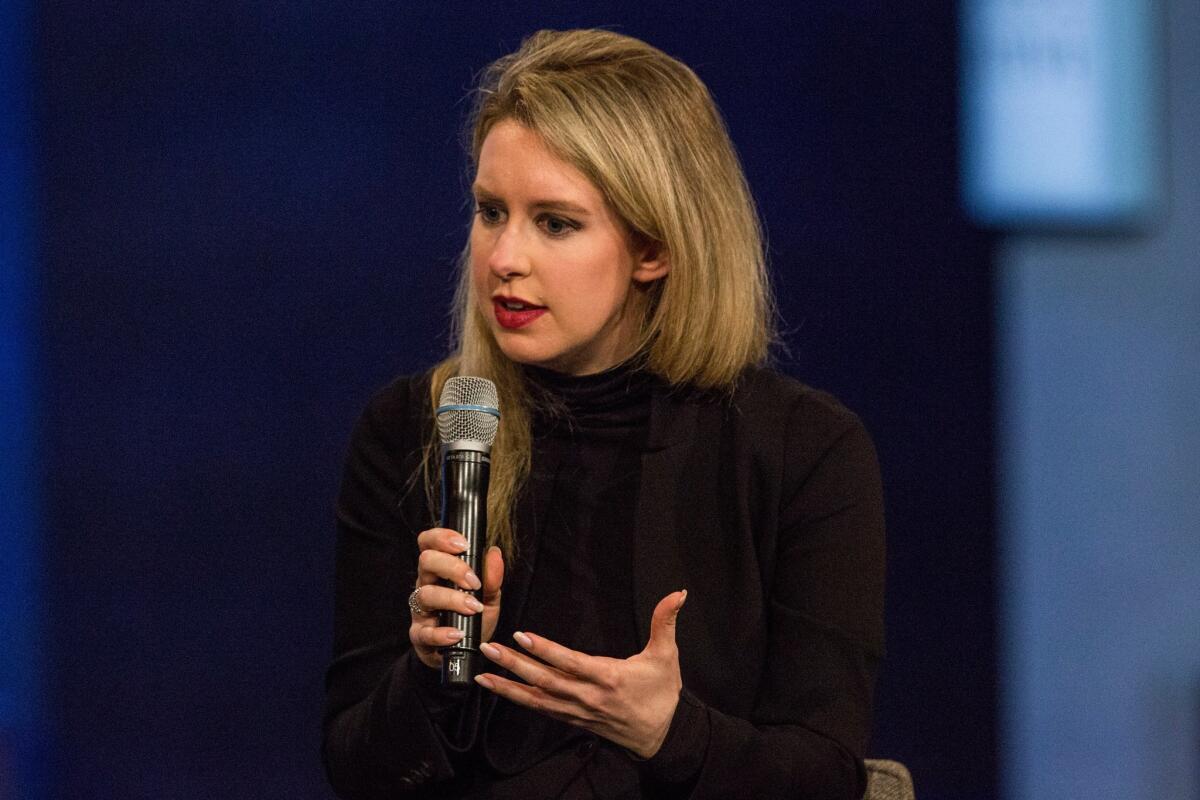

More than the reputation of Theranos and that of its entrepreneurial founder, 31-year-old Elizabeth Holmes, is at stake. Venture investors have poured a reported $400 million into Theranos on terms that value the firm at $9 billion; Holmes’ stake is said to be worth more than half that.

Yet much of the excitement about Theranos has always been based on irrelevant or misleading markers of success — or on Holmes as a personality. A profile in Inc. magazine this summer called her “America’s coolest billionaire” and featured such nuggets as a letter she supposedly wrote to her father at age 9 attesting, “What I really want out of life is to discover ... something that mankind didn’t know was possible to do.” She dropped out of Stanford in her sophomore year, Business Insider reported, because she decided that “her tuition money could be better put to use by transforming healthcare.” Her evocation of the image of Steve Jobs, down to her wardrobe of black turtlenecks, rarely went unremarked.

The most recent profile of her appeared just last week in a glossy feature supplement to the New York Times naming her among “Five Visionary Tech Entrepreneurs Who Are Changing the World.” The article focused not on the technological robustness of Theranos’ product, which outsiders haven’t been able to assess, but on the premasticated life history of Holmes, who “has always been a bit of an outlier. As a child, she studied with a tutor to become fluent in Chinese...” And so on.

(The article’s author, Laura Arrillaga-Andreessen, is the wife of Silicon Valley venture investor Marc Andreessen, though Theranos isn’t listed as a portfolio company of Andreessen Horowitz, his venture firm.)

What about that transformation of healthcare? In a widely viewed video of a talk she delivered last year at TEDMED, Holmes describes on-demand blood tests as an issue of personal empowerment. “When people have access to information about their own bodies,” she said, “they can change outcomes.”

That sounds unexceptionable, even laudable, but healthcare is more complicated. As John P.A. Ioannidis of Stanford Medical School observed for an article in the Journal of the American Medical Assn., Holmes’ talk ignored the drawbacks to expanded consumer-driven blood testing, such as “overdiagnosis, false-positive findings, or the potential for ... misplaced and perhaps overly zealous diagnostic and screening efforts.”

As it happens, questions had been raised about Theranos’ claims for months — but they had been swamped by a tide of fawning publicity. Ioannidis noticed that information about Theranos had appeared in the Wall Street Journal, Business Insider, Fortune and Forbes, “but not in the peer-reviewed biomedical literature.”

In many articles, the company’s choice to develop its technology secretly, as “stealth research,” was treated as a virtue. But to Ioannidis, it presented a risk: “Stealth research creates total ambiguity about what evidence can be trusted in a mix of possibly brilliant ideas, aggressive corporate announcements, and mass media hype.”

A few articles mentioned Theranos’ policy of keeping data and technical details out of public view. The New Yorker acknowledged that the secrecy “troubled” some observers, but then quoted an expert calling that “the Steve Jobs way.”

Writing in a peer-reviewed journal of clinical chemistry, Eleftherios P. Diamandis, a clinical pathology expert at the University of Toronto, asserted that the company’s pitch was based not merely on exaggerated claims for its own technology, but unwarranted criticism of competing technologies —traditional blood tests offered by companies such as Quest Diagnostics and Laboratory Corp. of America. Most of their tests cost as little and could be done as quickly as those Theranos was offering, he said.

One other aspect of Theranos’ publicity is the question of sexism — or, to be precise, reverse sexism. The youthful Holmes is a glamorous figure, tailor-made for the mass culture promotional machine. Part of her appeal is the supposed incongruity of someone of her youth, gender and charm achieving so much so quickly.

The received origin story of Theranos includes her friendship with former Secretary of State George Shultz, who was said (by Fortune) to have been “captivated” by her “purity of motivation,” among other qualities.

Now 93, Shultz joined the Theranos board and recruited many of his high-profile friends, including former Defense Secretary William Perry, former Sen. Bill Frist, and Henry Kissinger. Few of the board members had any real experience in the biomedical field. (Frist, a heart surgeon, hadn’t practiced in decades.) But their eminence was seen as validation of the company’s pitch.

It’s unquestionably possible that the questions about Theranos really do reflect inflated expectations about a truly transformative technology still in its developmental phase, as the company’s outside lawyer, David Boies, told the Wall Street Journal, and that in full bloom it really will change everyday diagnostics. But such transformations appear more rarely than one would conclude from the ease with which the term “revolutionary” is tossed around in Silicon Valley.

The lesson of Theranos may turn out to be that when investors and PR firms are all selling the same story, the proper response may be to “think different,” as Steve Jobs’ Apple ads used to say.

Michael Hiltzik’s column appears every Sunday. His new book is “Big Science: Ernest Lawrence and the Invention That Launched the Military-Industrial Complex.” Read his blog every day at latimes.com/business/hiltzik, reach him at [email protected], check out facebook.com/hiltzik and follow @hiltzikm on Twitter.

MORE FROM HILTZIK:

Here’s why you can’t believe everything economists write

Walmart stock bombs after a bombshell: It’s investing for the future

Hillary Clinton got one thing very right about Social Security -- but not everything

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.