NLRB case asks who’s really the boss of subcontractors’ workers

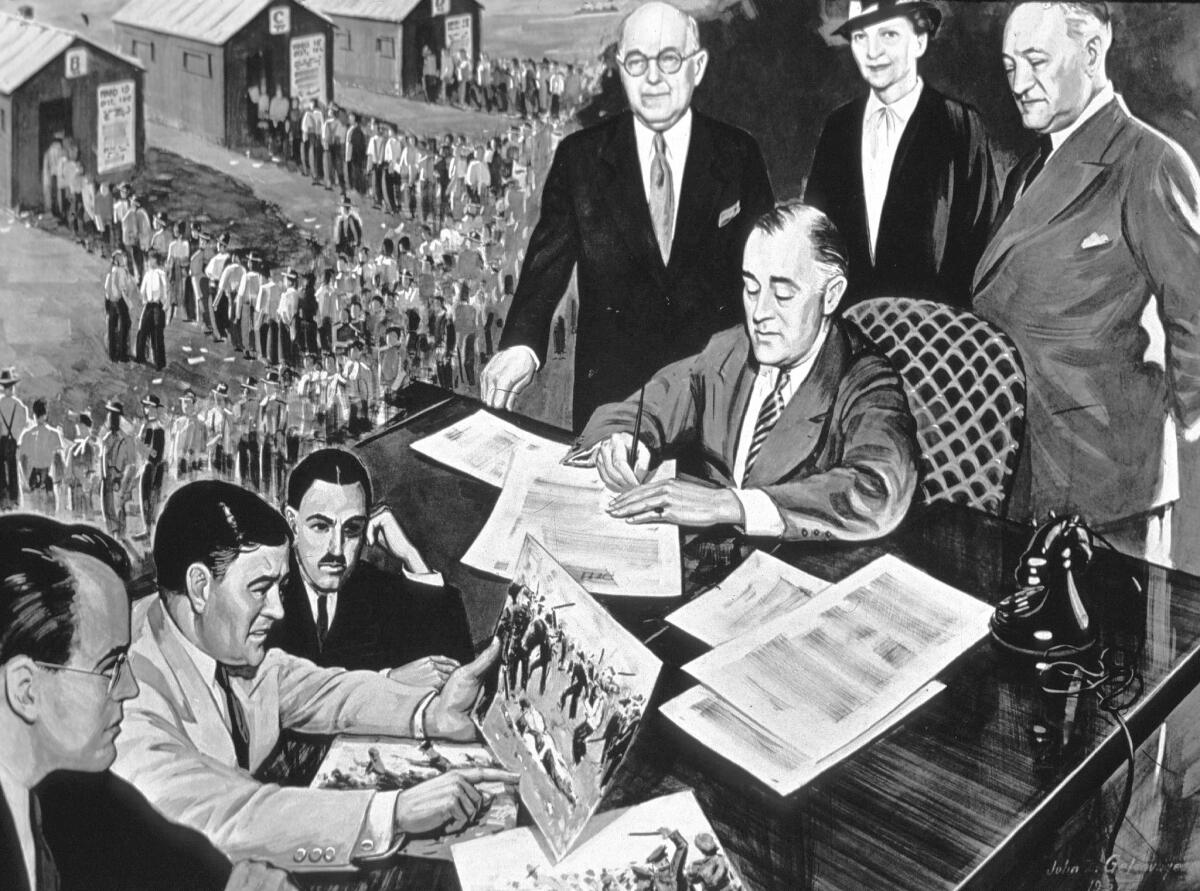

The practice of shifting employment to subcontractors or calling workers independent contractors helped inspire passage of the National Labor Relations Act signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1935.

While all eyes in the fight over how to define “employee” in the modern workplace are trained on companies such as Uber, an even more important battle involves another Silicon Valley employer — a lowly trash recycling center in Milpitas.

Yet that’s where the focus of the business and labor communities is these days, as they await a decision by the National Labor Relations Board on the status of some 120 workers employed as sorters of recyclable garbage.

The issue is whether they’re employees of the $9-billion waste-handling company Republic Services, which operates the site, or — as Republic asserts — merely of its subcontractor for temporary labor, Phoenix-based Leadpoint Business Services.

In the case brought by the Teamsters, the union maintains that Republic has sufficient control over the wages and work conditions of the Leadpoint workers to count as their joint employer with Leadpoint. The NLRB’s general counsel, which says it’s taking no position on the facts of the case, supports the Teamsters’ interpretation of the law.

A finding by the majority-Democratic NLRB that Republic and Leadpoint are joint employers would “upend American business practices,” according to the Competitive Enterprise Institute, an anti-regulation think tank.

From the standpoint of worker advocates, however, it would settle responsibility for the employees where it belongs, with the ultimate user of their labor, and protect them from workplace abuses.

Indeed, the shift of employer responsibility from Republic to its labor contractor shortchanged 193 Milpitas workers by a total of nearly $2.6 million in wages in 2012 and 2013, according to the city of San Jose, for which Republic runs the site. That’s because Republic maintains that its subcontractors weren’t named in the franchise agreement signed with the city, and therefore those workers weren’t covered by the city’s living-wage ordinance.

The Milpitas case — known as “Browning-Ferris” after the recycling facility’s former contractor, which eventually was merged into Republic — is one of several pending cases addressing whether a big company should share responsibility for the workers with intermediary hiring firms.

The most important target in these cases is McDonald’s, which effectively was designated a joint employer with its franchisees in a ruling last year by the NLRB’s general counsel. Dozens of charges alleging illegal treatment of McDonald’s store workers are pending against franchise holders and the fast-food giant. Hanging in the balance is the ability of the big companies to use franchise arrangements to obscure their role as the ultimate employer.

The NLRB cases are only the tip of the iceberg.

“This issue is creeping into almost every industry where Teamsters work,” including trucking, warehousing and food processing, says Doug Bloch, political director for San Francisco-based Teamsters Joint Council 7, which encompasses the local that filed the Milpitas complaint with the NLRB. The result is a “fundamental breakdown in the relationship between employers and employees, where nobody wants to take responsibility for the worker,” he says.

Think about the ride-hailing service Uber’s arm’s-length treatment of its drivers as nonemployees — or employing them via layers of contractors and subcontractors.

Yet there’s nothing new about companies averting responsibility for their workforce by shifting formal employment to subcontractors or calling workers independent contractors.

The spread of the practice in the garment industry in the 1920s and 1930s helped inspire passage of the National Labor Relations Act, which created the NLRB, in 1935. To counteract such dodges, the act’s definition of “employee” was written in the broadest terms. The collective bargaining and other labor rights it grants, the act states, are “not ... limited to the employees of a particular employer.”

That language “explicitly contemplates that employees often work for entities that are in a supply chain or within a network of relationships,” says Catherine Fisk, a labor expert at the UC Irvine law school. Congress recognized “then as now, that meaningful collective bargaining might require organizing across the boundaries of particular corporate forms,” she says.

In a brief filed with the NLRB, Republic maintains that the Teamsters and the NLRB’s general counsel are attempting “a wholesale rewrite” of the law, expanding the term “employer” in a way that’s “contrary to the act’s language and legislative history.”

Actually, the union and general counsel say they’re seeking a return to the term’s original meaning. The current standard says that only those with direct authority over a worker can be regarded as an “employer.” But according to an amicus brief by the general counsel, the traditional standard held that an employer was anyone with “direct or indirect control over working conditions.”

The narrowing began during the Reagan administration, but it’s now at odds with the modern reality of employment. Starting around 1975, the general counsel’s brief observes, temporary employment agencies expanded from providing short-term clerical staff and day laborers to providing “maintenance work, custodial services, legal services, and computer programming,” doubling as a share of the workforce between 1990 and 2000. Today the handoff of essential workers “inhibits meaningful collective bargaining,” which the act is designed to empower.

It can also deprive workers of fundamental wage and hour protections. Republic’s disavowal of the recycling center’s employees led to the workers being shortchanged by as much as $7.48 an hour, the difference between their wage rate and San Jose’s living-wage minimum, which was $15.98 from July 2012 through June 2013, and $17.03 thereafter, according to the city. In December 2013, the city ordered Republic to pay back wages of $13,397 to each of 193 workers and assessed the company a penalty of $7.8 million.

Republic, however, maintains that the employees are beyond the reach of the living-wage ordinance. The matter is still under mediation, according to Nina Grayson, San Jose’s director of equality assurance. My calls to attorneys for Republic were unanswered.

The juggling of responsibility wouldn’t matter so much if all employers were equally committed to their workers’ welfare. But the expansion of these arrangements has coincided with a systematic erosion of wage and hour rights — and that’s almost certainly no coincidence.

“The bottom line,” says the Teamsters’ Bloch, “is who’s the boss?” The first thing that gets lost whenever there’s confusion over the answer is the rights of the employees.

Michael Hiltzik’s column appears every Sunday. His new book is “Big Science: Ernest Lawrence and the Invention that Launched the Military-Industrial Complex.” Read his blog, the Economy Hub, every day at latimes.com/business/hiltzik, reach him at [email protected], check out facebook.com/hiltzik and follow @hiltzikm on Twitter.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.