Watch the U.S. age before your eyes in this amazing animated graphic

The aging of the U.S. population is, well, a fact of life that gets mentioned often in political and economic discussions but seldom is communicated in an understandable way. Stephen Holzman, who appears to be something of a data visualization whiz, decided to pull together the statistics and animate them via the gif below.

The most striking element of the graphic, unsurprisingly, is the movement of baby-boomers through the population, seen as a very distinctive bulge appearing in the mid-1940s and moving up in age through about 2040, at which point it begins to fade. But the most important point is that the population as a whole is aging. (The red and blue bands on the graphic reflect the uncertainties of population statistics starting in 2010.)

The World Economic Forum reproduced Holzman's graphic for a discussion of the implications of the trend, which roughly parallels that in the rest of the world. "The potential consequences of an aging population," observes the WEF, "include economic pressure on healthcare and other welfare systems and a much smaller working-age population relative to the elderly."

The potential consequences of an aging population...includeeconomic pressureon healthcare and other welfare systems and a much smaller working-age population relative to the elderly.

— --World Economic Forum

The trend will be most pronounced in less-developed countries, according to U.N. population surveys. "The world’s least developed countries will go from having around 16 working age people for every older person to around 4 by the end of this century," the WEF says. "The developed world by contrast...currently has 3.7 people of working age for every older person and this is expected to fall to 1.9 by the end of the period."

Yet the social and economic prospects are not as dire as they appear on the surface. Improvements in healthcare mean that "what it meant to be 65 in 1916 (or 1933) is no longer the same as what it means to be 65 today." Indeed, our measurements of aging itself are themselves aging, for they fail to accommodate the improvement in the ability of people to keep working into later years--generally, that is, for vast and widening gaps have appeared in life expectancies among ethnic and socio-economic categories.

Population economists Warren Sanderson and Sergei Scherbov propose recalibrating measures such as old-age dependency ratios to recognize such emerging trends. "The old-age dependency ratio in the U.S. is forecast to increase by 61% from 2013 to 2030," they observe. "But using our economic dependency ratio, the ratio of adults in the labor force to adults not in the labor force increases by just 3% over that period. Clearly, doom-and-gloom stories about U.S. workers having to support so many more nonworkers in the future may need to be reconsidered."

That has implications for the fiscal stability of Social Security. Among other things, many workers will continue contributing to the program for years after they were formerly assumed to transition to beneficiary status, and many more may defer collecting until they approach the age of 70.

The impact on healthcare costs of aging populations may also become more moderate. Existing projections assume "that health care costs rise dramatically on people’s 65th birthdays," they write. But the prospects are that the heaviest costs, which occur in the last few years of life, may occur at later ages than currently expected. In Japan, for example, when the burden of the healthcare costs of people aged 65 and up on those 20 to 64 years old is assessed using only the conventional old-age dependency ratio, that burden is forecast to increase 32% from 2013 to 2030," write Sanderson and Scherbov. "When we compute healthcare costs based on whether people are in the last few years of their lives, the burden increases only 14%.

In Japan, for example, when the burden of the health care costs of people aged 65 and up on those 20-64 years old is assessed using only the conventional old-age dependency ratio, that burden is forecast to increase 32 percent from 2013 to 2030," write Sanderson and Scherbov. "When we compute health care costs based on whether people are in the last few years of their lives, the burden increases only 14 percent.

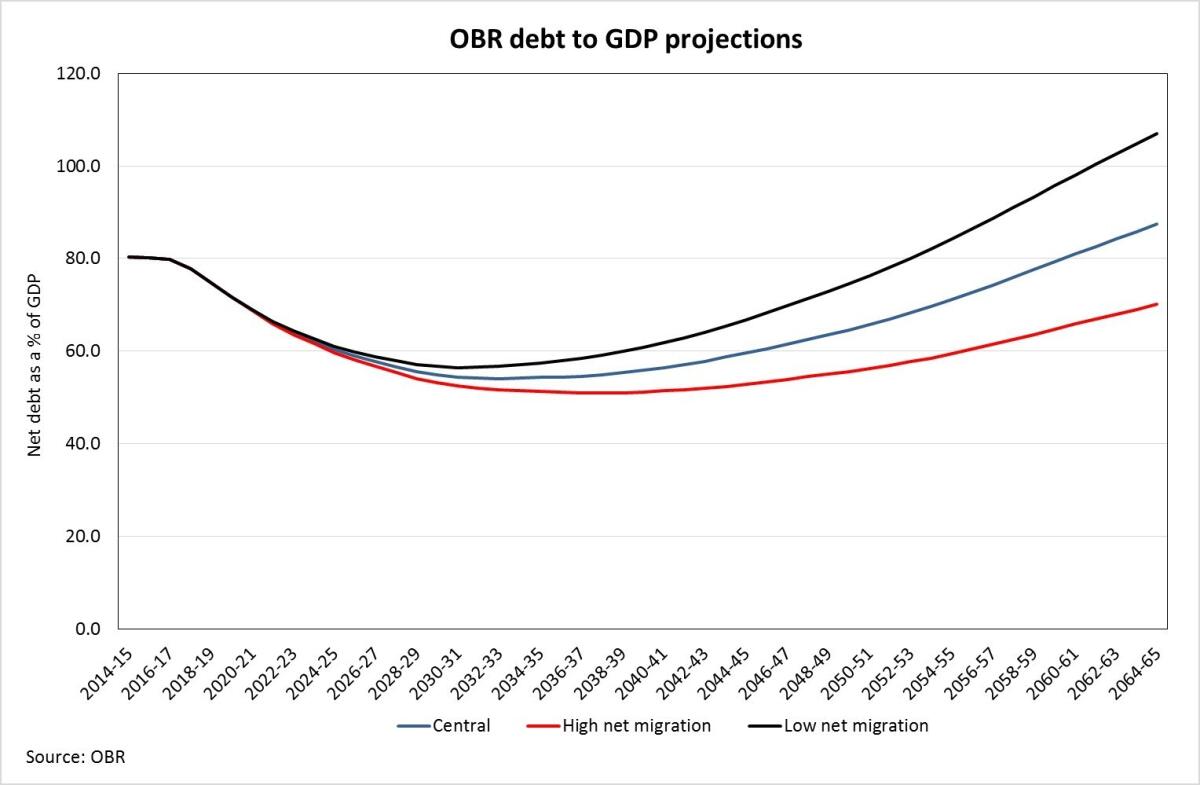

One lesson drawn from the reality of aging populations in the developed world involves the value of immigration. "Migrant workers are typically of working age which means they help to boost the labour supply and contribute to economic growth and tax revenues," the WEF observes. The accompanying chart from Britain's Office for Budget Responsibility shows that by the mid-2060s, low immigration could result in debts rising to over 100% of GDP; higher immigration would reduce the ratio to only 70%.

Understanding of the policy dimensions of aging demographics have lagged far behind the reality. For the most part, they're stuck in the past. It's time to bring them up to date and strip them of ideological bluster. Seeing how the population ages is a good first step, and for that we should thank Mr. Holzman.

Keep up to date with Michael Hiltzik. Follow @hiltzikm on Twitter, see his Facebook page, or email [email protected].

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.