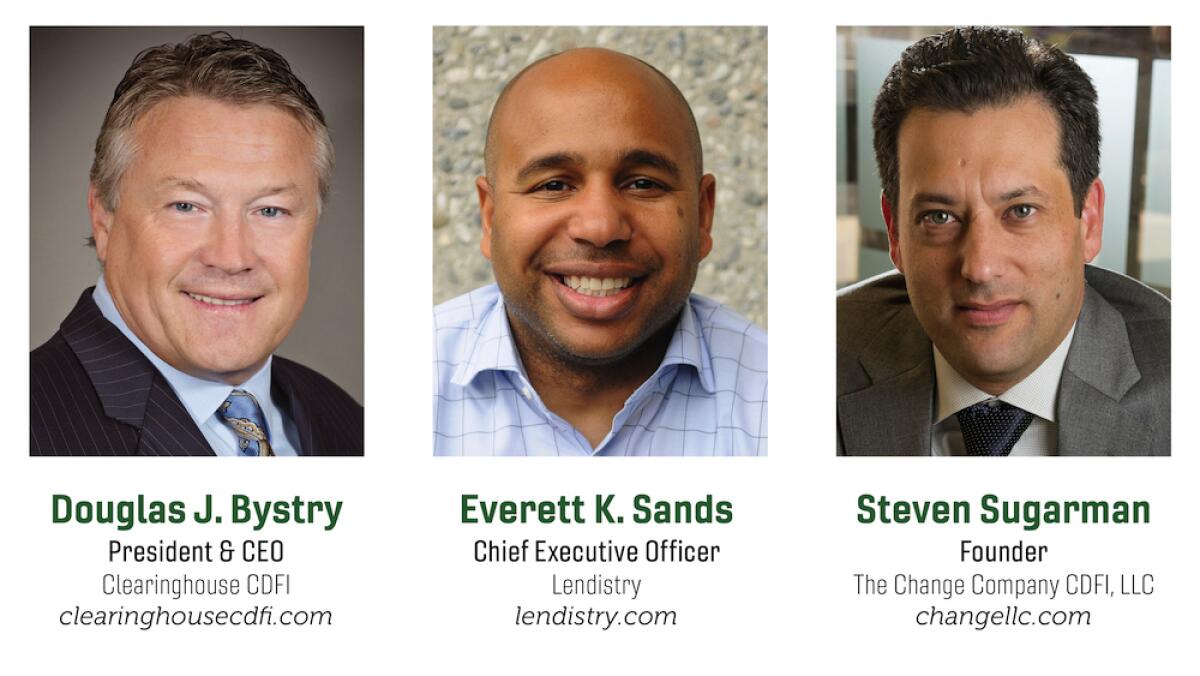

Q&A: Exploring CDFI’s Role In Closing The Racial Wealth Gap

To take a closer look at the CDFI landscape and what is needed to get capital into underbanked communities, we have turned to some of the region’s leading experts – in community finance, diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI), and public policy. These leaders answered our questions and shared their insights on the state of CDFIs in 2021 and moving forward.

Q: Is the government doing enough to help CDFIs serve the underbanked?

Douglas J. Bystry, President & CEO, Clearinghouse CDFI: Recently, the government has recognized the role CDFIs play-in financial services to low-income communities by increasing funding and support from the Treasury Department. At the same time, bureaucratic delays, outdated regulations, and other processes that slow down the growth of CDFIs have hindered our ability to do more.

Everett K. Sands, Chief Executive Officer, Lendistry: The recent activities by the government to add additional capital to the CDFI Fund is positive. There are a couple of additional items which could help further the CDFI Fund’s mission: a) Asking the CDFI Fund to be accountable to whom it awards capital; b) Allowing for larger capital programs (CDFI Bond Fund, NMTC) to be accessible to smaller institutions/encourage collaborations between larger and smaller CDFIs; and c) Increase the funding to CDFIs and make capital allocations permanent.

Steven Sugarman, Founder, The Change Company CDFI, LLC: Sadly, the government can be doing so much more to help non-bank CDFIs.

Expanding financial services in minority and underbanked communities requires the inclusion of non-bank CDFIs in government programs. Unfortunately, the government still excludes non-bank CDFIs from many of the most important programs. The vast majority (over 90%) of non-bank community development financial institutions continue to be ineligible to partner with the Federal Reserve, are excluded from the most impactful treasury programs, and are forced into second-class membership at the government-sponsored enterprises who are supposed to provide them and their communities access to capital. It is time for the federal government to truly partner with non-bank CDFIs who serve the underbanked and communities ignored by traditional banks. This would involve the full deployment of budgeted and funded programs, like the CDFI Bond Guarantee Fund, and equal membership rights to bank members at the federal home loan banks. As a case in point, non-bank CDFIs were not approved as PPP lenders for months and the underbanked borrowers they serve were forced to wait for relief during COVID.

Today, the Small Business Administration still refuses to issue non-bank SBA preferred lender licenses to non-bank CDFIs, instead keeping in place a “moratorium” on such licensing opportunities. The racial wealth gap is larger today than it was when The Fair Housing Act of 1968 was signed into law more than a half century ago. We hope that the government will revisit its current approach to non-bank community development lenders and include them as a core part of the solution.

Q: What new government policy would you like to see implemented to help the underbanked?

Sands: Coordination between the FHFA and CDFI Fund. FHFA, which oversees the Federal Home Loan Bank (FHLB), does not allow CDFIs to pledge all of the assets it allows banks to pledge (for example small business loans). Capital from the CDFI Fund could be leveraged to provide guarantees/credit enhancements to the FHLB, which would allow additional capital to flow to CDFIs and consequently underserved communities.

Sugarman: The most important policy change that could be made would be for the Federal Housing Finance Authority to ensure CDFIs are provided equal access to the Federal Home Loan Banking system as promised by the Obama Administration when it signed HERA into law. It is sad that almost a decade later most FHLB Banks still lend less than 0.01% of their capital to finance the liquidity of CDFI members. This is not due to credit quality or economic considerations, but an old school regulatory view (initially implemented as part of regulatory redlining during the Jim Crow era) that when the government helps to finance CDFI loans to minority and loan income communities they are taking on heightened reputation and credit risk. In short, if the FHLB system does not lend to CDFIs, it will never have the reputation risk of seeking to collect from CDFIs. Meanwhile, the minority borrowers served by CDFIs are the hardest hit.

Bystry: Payday lending is out of control, targeting and then harming low-income areas. These bad actors must be reined in. Additionally, Credit Unions should have CRA obligations, just like banks.

“Closing the racial wealth gap today could add $5 trillion of additional GDP over the next five years. And if we are serious about closing this gap, CDFIs and the access they provide to homeownership need to be at the top of the list.”

— -- Sugarman

Q: Have you been able to raise capital from both regulated companies (E.G., banks and insurance) and unregulated companies (E.G., Corporations and asset managers) who are ESG-focused?

Sugarman: Yes, we have been able to raise capital from both. Netflix invested $10 million in The Change Company’s initiative as part of their $100-million Black Economic Initiative. This year, we have also raised $250 million from a consortium of 85 high-quality insurance companies, asset managers, banks, and ESG investors. Frankly, the only entities that we have had trouble partnering with are government agencies purportedly set up to help CDFIs and underbanked borrowers.

Bystry: We raise capital from banks, which have done more than their fair share. Insurance companies could do much more to support CDFIs. Unregulated companies and other ESG funds have done very little in this field and are using investment screens to promote ESG, rather than supporting CDFIs that are truly making impactful loans and investments benefiting low-income communities.

Sands: We have not raised capital from insurance companies, corporations and/or ESG-focused asset managers. We have raised capital from banks.

“We have 22 consecutive years of profitability paying a consistent dividend, yet we still struggle to attract capital to grow and enter new markets.”

— --Bystry

Q: What is the biggest challenge you face serving the underbanked?

Bystry: Attracting equity capital continues to be our biggest challenge and restraint. We have 22 consecutive years of profitability paying a consistent dividend, yet we still struggle to attract capital to grow and enter new markets.

Sands: Raising the capital needed to provide scalable impact.

Sugarman: Racial inequities, which are pervasive throughout the financial services industry, are far and away the greatest challenge. Fixing the old-school banker mindset that minority lending is higher-risk lending requires a structural change in the mindset of those at all levels in the financial services sector. We recently spoke to a private equity investor who said his firm avoids involvement with CDFIs because “if something goes wrong with the loans, there is a huge reputational risk” – that is the very definition of denying people access to capital for non-economic reasons. This systemic racism results in a wealth gap that does real and measurable damage to our entire economy. According to a recent study by the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, if racial wealth gaps had been closed 20 years ago, U.S. GDP could have benefitted by an estimated $16 trillion. Closing the racial wealth gap today could add $5 trillion of additional GDP over the next five years. And if we are serious about closing this gap, CDFIs and the access they provide to homeownership need to be at the top of the list.

Q: Where is the most need for increased support to serve the underbanked and what needs to be done now?

Sands: More responsible/patient capital is needed for allowable scalable institutions like Lendistry the opportunity to provide access to capital to underserved communities.

Sugarman: The unequal cost of homeownership for Black, Latino, and low-income communities is one of the persistent problems faced by the underbanked. When access to homeownership is not evenly distributed, the racial wealth gap grows and Black, Latino, and low-income communities continue to fall farther and farther behind. While a lot of systemic changes are going to be necessary to address that problem, one near-term solution is to support the expansion of CDFIs, making access to them more widely available and providing them the necessary capital to grow their operational footprint. According to an MIT study, The Unequal Costs of Black Homeownership, the average Black family spends over $67,000 more than the average white family for the same home loan in America (interest and fees), and this is exactly the type of structural economic inequality that we seek to change. CDFIs like ours can provide home loans with fair and responsible terms to Black, Latino, and low-income communities saving tens of thousands of families, literally billions of dollars over the lives of their loans.

“Capital from the CDFI fund could be leveraged to provide guarantees/credit enhancements to the FHLB, which would allow additional capital to flow to CDFIs and consequently underserved communities.”

— -- Sands

Bystry: Big companies and governmental institutions. Insurance companies and other corporations could serve the underbanked by supporting CDFIs. The CDFI Fund should cut out obsolete rules to allow for CDFIs to grow and increase our market share of making loans in low-income communities.

FHFA and Federal Home Loan Bank need to make sure CDFIs are represented on governing boards and in setting policies that impact how capital is made available to low-income populations.